Sailing a ship under a flag of convenience is a popular business practice, commonly chosen for saving money, but the biggest part of controversy surrounding this practice is the implications it creates for seafarers’ rights. But what does this practice exactly refer to?

In simple terms, a flag of convenience ship is one that flies the flag of a country other than the country of ownership. This enables shipowners to “escape” inconvenient regulations of their home country. Flags of convenience are often registries that do not have nationality requirements for the shipping companies that use their flag – often because they actually do not have any shipping companies incorporated. Despite being a common and not strictly negative practice, switching to FOC is generally controversial and not well-received. But let us take things from the beginning.

Have you ever wondered what the exact role of flag states is in shipping? Flag states are important for making sure that the vessel is seaworthy and complies with regulatory standards on safety, labor and environment. The landmark UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is providing the responsibility for ships to be registered under the flag of the state under whose regulatory control it falls, but UNCTAD data show that almost 73% of the world fleet is flagged in a country other than that of the vessels’ beneficial ownership. Why is this happening?

Did you know?

Although China, Japan, Greece and the US are the top ship owning countries for 2021 – Panama, Marshall Islands and Liberia are by far the top three flag registries.

Why is FOC a common practice?

The term “convenience” is not random. Although typical national registries often have some basic requirements, such as the ship to employ at least half citizens onboard and to be owned and constructed by national interests, open registries most commonly offer the ease of on-line registration with few questions asked. But, generally, the most common reasons for choosing a different flag are:

- tax avoidance,

- cheap registration fees

- escaping national labor and environmental regulations,

- ability to hire crews from lower-wage countries.

A glance of history

In the modern era, the practice of ships being registered in a foreign state was first seen during the US alcohol Prohibition in the 1920s, when shipowners seeking to serve alcohol to passengers registered their ships in Panama. However, the benefits of lighter regulations and decreased costs kept this trend going even after Prohibition ended.

The sinking of the Liberian-flagged VLCC Amoco Cadiz in March 1978, claiming the title of one of the world’s worst tanker oil spills ever, and the subsequent public outcry of the incident paved the way for the Paris Memorandum of Understanding on Port State Control (Paris MoU) in 1982, in a bid to address the need for a new type of maritime enforcement that made ships in international trade subject to inspection by the states they visit.

What do FOC mean for seafarers?

Flags of Convenience is a hot topic among seafarers’ rights advocates. For example, global trade union ITF has stressed repeatedly how FOC registries make it more difficult for unions, industry stakeholders and the public to hold ship owners to account, as a Flag of Convenience does not necessitate a seafarer’s basic rights. For example:

- Compensation: Seafaring is a risky profession, but in case of an accident, a ship under flag of convenience may refuse to pay a compensation to the seafarers and/or their family.

- Wages: FOC leave an open ground for violations of seafarers’ pay rights, with many cases reported where seafarers were not paid their salary, or the salary was delayed.

- Resting period: Ensuring proper implementation of MLC is problematic in general but is even more challenging on ships with substandard implementation of guidelines, so seafarers may not be allowed to rest properly, leading to adverse effects for their long-term wellbeing as well as for ship safety.

- Risky working conditions: FOC ships are generally more prone to lower standards onboard, in terms of safety and hygiene, which could lead crews working in hazardous conditions.

Besides the direct -commonly negative- consequences they bring for seafarers, loose regulations make it easier for FOC ships to be involved in illegal activities, including drug smuggling. This can lead to unfair criminalization of seafarers who may find themselves involved in illegal actions without knowing it. Insufficient regulatory oversight makes FOC also a popular choice for the last voyages of ships, most often beached in breaking yards in South Asia.

DO YOU KNOW?: Read in this series

“End-of-life registries such as St Kitts and Nevis and Comoros compete with each other by offering low-cost “last voyage” packages and expressly state that no nationality requirements need to be fulfilled in order to register under their flags – not even the setting up of a shell company. Typically, this includes fast-track registration procedures, valid only for a very limited period of time, at a special lower price,

…NGO Shipbreaking Platform explains.

Did you know?

Every year, Paris MoU issues performance lists for flag states, based on the total number of inspections and detentions during a 3-year rolling period. The “White, Grey and Black (WGB) List” presents the full spectrum, from quality flags to flags with a poor performance that are considered high or very high risk. As expected FOC may be found within the grey- or black-listed areas, due to poor implementation of international maritime standards with states such as Comoros, Tuvalu, Togo, Belize, Tanzania, and Sierra Leone being the usual suspects as per industry insiders.

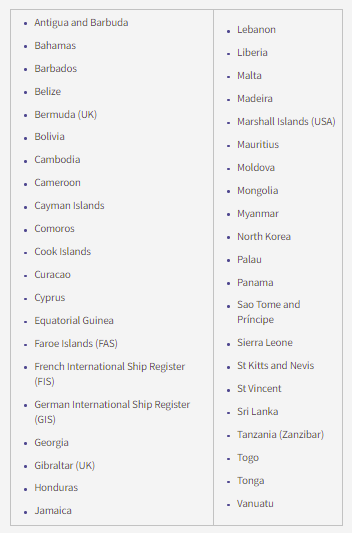

List of FOC states

ITF’s fair practices committee has declared as declared FOCs the following countries:

Can longline fishing vessels with Foreign Ownership flagged in Fiji be considered as FOC. Notwithstanding that Fiji isnt!