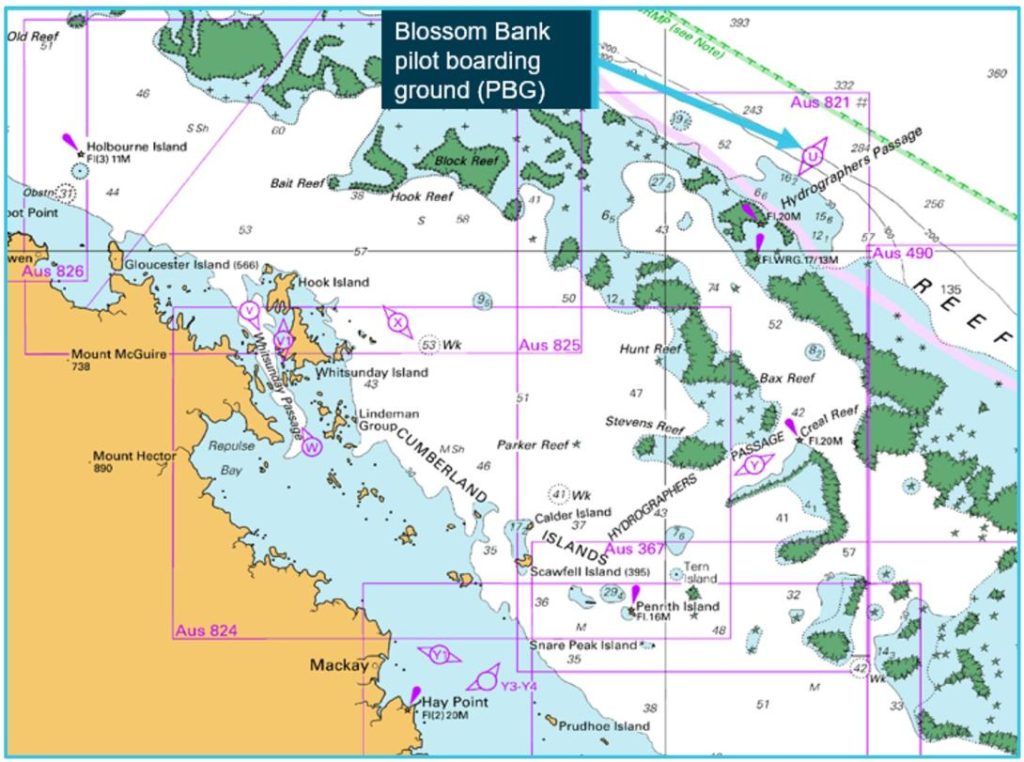

The Australian Transport Safety Bureau (ATSB) published the investigation on an incident in which a bulk carrier came within 200 m of grounding in the Great Barrier Reef, after a GPS unit onboard the ship began providing false information to the pilot and crew on board.

The incident

At about 0311 local time on 4 May 2022, the 225 m bulk carrier Rosco Poplar was transiting the Great Barrier Reef via Hydrographers Passage under the conduct of a coastal pilot. Upon suddenly noticing that a reef sector light was indicating red, the pilot ordered a course correction. This was followed almost immediately by the activation of an alert from the ship’s electronic navigational equipment indicating that the ship was passing less than 200 m from Bond Reef (normal clearance was about 1,500 m). The ship’s course was corrected and the remaining pilotage was conducted uneventfully.

What the ATSB found

The ATSB found that during the early stages of the pilotage, one of the ship’s 3 GPS units began outputting incorrect positional data, likely due to an antenna malfunction. Because the bridge navigational equipment, including the electronic chart display and information system (ECDIS), radars and automatic identification system (AIS), were receiving a single position input from the same GPS unit, the ship’s position was incorrectly displayed on all these systems. However, no alarms were triggered from the failure because the GPS unit incorrectly indicated that position accuracy was within acceptable limits.

The investigation found that the pilot and bridge team solely relied on GPS positioning to monitor the ship’s progress and did not maintain a proper lookout through use of radar and visual observations. As a result, they did not identify that the position reported on the ECDIS units was incorrect and that the ship had deviated significantly from the planned track.

It was also identified that the pilot had not correctly configured their portable pilot unit (PPU) to be independent of the ship’s position sensors. This resulted in the PPU displaying the same incorrect position as the ship’s ECDIS units.

Additionally, ineffective pilotage and bridge resource management (BRM) contributed to the occurrence. An inadequate master-pilot information exchange did not establish individual roles and responsibilities for watchkeeping and communication, while the second mate was given tasks which distracted them from their duties for monitoring the passage plan and maintaining a proper lookout. As a result, the pilot and bridge team’s situation awareness progressively declined in the absence of adequate communication and a shared mental model of the pilotage.

The ATSB also identified that, following receipt of an unusual grounding alert display associated with the Rosco Poplar’s GPS malfunction, the vessel traffic services operator assessed it as erroneous. Consequently, the pilot and ship’s crew were not provided with timely advice of the indicated proximity to Bond Reef.

Finally, the ATSB identified that the check pilot system implemented by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) did not provide the intended competency assurance. The investigation identified significant variations in the application of assessment standards between individual check pilots, indicating that assessment outcomes were not a valid and reliable indicator of competency. Further, due to the absence of any processes for analysing assessment results, AMSA had not identified these inconsistencies.

Contributing factors

Contributing factors

- Rosco Poplar’s GPS unit probably malfunctioned due to a fault with its antenna, resulting in erroneous ship’s position data. This incorrect data was then provided to all navigational aids, including both electronic chart display and information system (ECDIS) units, automatic identification system (AIS) and the pilot’s portable pilotage unit (PPU).

- The PPU had not been configured as required to source position data independent of the ship’s GPS unit.

- The pilot and the ship’s bridge team were relying solely on the PPU and ECDIS units to monitor the ship’s progress. Consequently, they did not identify that the ship had deviated from the planned track until the GPS unit reset and began indicating the correct position, which was about 200 m from Bond Reef.

- The pilotage was not conducted appropriately, including effective track monitoring and proper bridge resource management, due to a combination of:

- an inadequate master and pilot information exchange

- roles and responsibilities not being properly defined

- an absence of monitoring using visual bearings and radar, including parallel indexing

- non-essential tasks for the pilotage phase that distracted the bridge team

- the absence of a shared ‘mental model’ of the pilotage.

Other factors that increased risk

- The configuration of Rosco Poplar‘s electronic navigation equipment was vulnerable to single GPS unit errors because, at any given time, only one of the ship’s 3 GPS units could be selected to provide positional data to all the ship’s navigational equipment.

- Following receipt of an unusual grounding alert display associated with the Rosco Poplar’s GPS malfunction, the vessel traffic service operator assessed it as erroneous. Consequently, the pilot/ship’s crew were not provided with timely advice of the indicated proximity to Bond Reef.

- The check pilot system was ineffective in providing the Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) assurance of the competency of coastal pilots, mainly due to the inconsistent and unreliable application of assessment standards between different check pilots. Further, AMSA had not implemented a system to identify the inconsistent application of standards or the trends in assessment outcomes readily apparent in the data that it had held for many years.

Safety message

The occurrence highlights that the various concepts, techniques, and attitudes that together comprise bridge resource management are essential defences against human error. In confined waters such as compulsory pilotage areas, the margins for navigation errors are significantly reduced. Effective communication and coordination between the pilot and bridge team are necessary requirements for establishing a shared mental model of the pilotage so that evolving and critical situations can be identified and appropriately managed.

Compulsory coastal pilotage remains an essential defence against serious shipping accidents in the Great Barrier Reef. It is therefore important that coastal pilots meet necessary competency and performance standards. Furthermore, any assessment system that assures those standards must produce consistent and accurate outcomes. If sufficient measures are not implemented to ensure assessment standards are interpreted and applied consistently irrespective of the assessor, the outcomes are unreliable.

ATSB Chief Commissioner Angus Mitchell stated that inadequate master-pilot information exchange led to unclear roles and responsibilities for watchkeeping and communication, distracting the second mate from monitoring the passage plan and maintaining a proper lookout. He emphasized the importance of effective bridge resource management, underscoring that compulsory coastal pilotage is essential for preventing serious shipping accidents in the Great Barrier Reef.

Furthermore, he added that coastal pilots must meet consistent assessment standards for reliable outcomes, noting that insufficient measures can result in unreliable assessments, ultimately hindering timely navigation advice regarding proximity to Bond Reef.