In fact, the UN Environment Programme Emissions Gap Report for 2019 which was launched on Tuesday, November 26, warns that the world is heading for a 3.2 degrees Celsius global temperature rise over pre-industrial levels, leading to even wider-ranging and more destructive climate impacts, even if countries meet commitments in accordance with the 2015 Paris Agreement.

As the world strives to cut greenhouse gas emissions and limit climate change, UNEP’s Emissions Gap Report has compared where greenhouse gas emissions are heading against where they need to be and highlight best ways to bridge the gap.

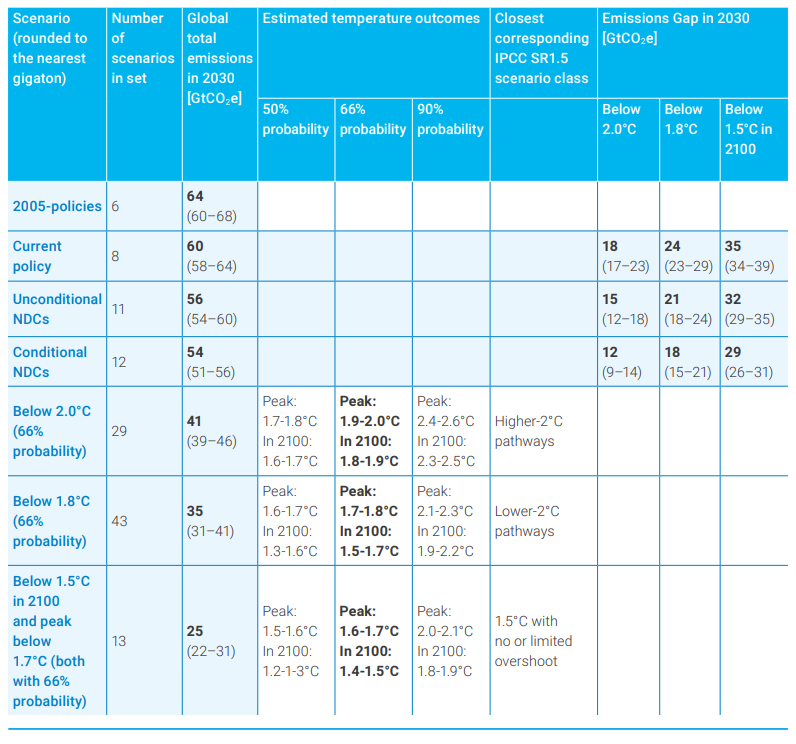

The report in particular, reflects on the latest data on the expected gap in 2030 for the 1.5°C and 2°C temperature targets of the Paris Agreement. It further considers different scenarios, such as the absence of new climate policies since 2005 as well as the full implementation of all national commitments under the Paris Agreement. It also looks at how large annual cuts would need to be from 2020 to 2030 to stay on track to meeting the Paris goals.

Notably, the annual Emissions Gap Report, highlights that emissions need to fall by 7.6% each year over the next decade, if the world is to get back on track towards the goal of limiting temperature rises to close to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

UNEP’s Executive Director, Inger Andersen underlined that

Our collective failure to act early and hard on climate change means we now must deliver deep cuts to emissions.

UNEP further advises that if the world warms by more than 1.5 degrees, “we will see more frequent, and intense, climate impacts,” such as the heatwaves and storms witnessed in recent years.

The UNEP report, which compares where greenhouse gas emissions are heading compared to where they need to be calls on all countries to reduce their emissions, and substantially increase their “Nationally Determined Contributions” made under the Paris Agreement, and further put policies into place in order to implement them during 2020.

Specifically, the Report found that

1. GHG emissions continue to rise, despite scientific warnings and political commitments.

There is no sign of GHG emissions will be hitting the highest point in the next few years; every year of postponed peaking means that deeper and faster cuts will be required. By 2030, emissions would need to be 25% and 55% lower than in 2018 to put the world on the least-cost pathway to limiting global warming to below 2˚C and 1.5°C respectively.

Moreover, economic growth has been much stronger in non-OECD members, growing at over 4.5% annually in the last decade compared with 2% per year in OECD members. Since OECD and non-OECD members have had similar declines in the amount of energy used per unit of economic activity, stronger economic growth means that primary energy use has increased much faster in non-OECD members by 2.8% per year, than in OECD members by 0.3% per year.

2. G20 members account for 78% of global GHG emissions. Collectively, they are on track to meet their limited 2020 Cancun Pledges, but seven countries are currently not on track to meet 2030 NDC commitments, and for a further three, it is not possible to say.

It is added that it should be the world’s most developed economies, the G20, that should take the lead as they contribute to 78% of all emissions. Yet, only five of these countries have currently committed to a long-term zero emissions target.

Nevertheless, it is said that many governments, cities, businesses and investors are engaged in ambitious initiatives to lower emissions.

According to UNEP, it is developing countries that suffer disproportionately from climate change, yet, they can learn from efforts in developed countries, and perhaps even overtake them, adopting cleaner technologies at a faster rate.

3. Although the number of countries announcing net zero GHG emission targets for 2050 is increasing, only a few countries have so far formally submitted long-term strategies to the UNFCCC.

Namely, an increasing number of countries to have set net zero emission targets domestically and 65 countries and major subnational economies, such as the region of California and major cities worldwide, have committed to net zero emissions by 2050. However, only a few long-term strategies submitted to the UNFCCC have so far committed to a timeline for net zero emissions, none of which are from a G20 member.

4. The emissions gap is large; in 2030, annual emissions need to be 15 GtCO2e lower than current unconditional NDCs imply for the 2°C goal, and 32 GtCO2e lower for the 1.5°C goal.

The report presents an assessment of global emissions pathways relative to those consistent with limiting warming to 2°C, 1.8°C and 1.5°C, in order to provide a clear picture of the pathways that will keep warming in the range of 2°C to 1.5°C. The report also includes an overview of the peak and 2100 temperature outcomes associated with different likelihoods. The inclusion of the 1.8°C level allows for a more nuanced interpretation and discussion of the implication of the Paris Agreement’s temperature targets for near-term emissions.

5. Dramatic strengthening of the NDCs is needed in 2020. Countries must increase their NDC ambitions threefold to achieve the well below 2°C goal and more than fivefold to achieve the 1.5°C goal.

Further delaying the reductions needed to meet the goals would imply future emission reductions and removal of CO2 from the atmosphere at such a magnitude that it would result in a serious deviation from current available pathways. This, together with necessary adaptation actions, risks seriously damaging the global economy and undermining food security and biodiversity.

6. Enhanced action by G20 members will be essential for the global mitigation effort.

Based on the assessment of mitigation potential in the seven previously mentioned countries, several areas have been identified for urgent and impactful action. The purpose of the recommendations is to show potential, stimulate engagement and facilitate political discussion of what is required to implement the necessary action, with each country being responsible for designing their own policies and actions.

7. Decarbonizing the global economy will require fundamental structural changes, which should be designed to bring multiple co-benefits for humanity and planetary support systems.

Climate protection and adaptation investments will become a precondition for peace and stability, and will require unprecedented efforts to transform societies, economies, infrastructures and governance institutions. At the same time, deep and rapid decarbonization processes imply fundamental structural changes are needed within economic sectors, firms, labor markets and trade patterns.

By necessity, this will see profound change in how energy, food and other material-intensive services are demanded and provided by governments, businesses and markets. These systems of provision are entwined with the preferences, actions and demands of people as consumers, citizens and communities. Deep-rooted shifts in values, norms, consumer culture and world views are inescapably part of the great sustainability transformation.

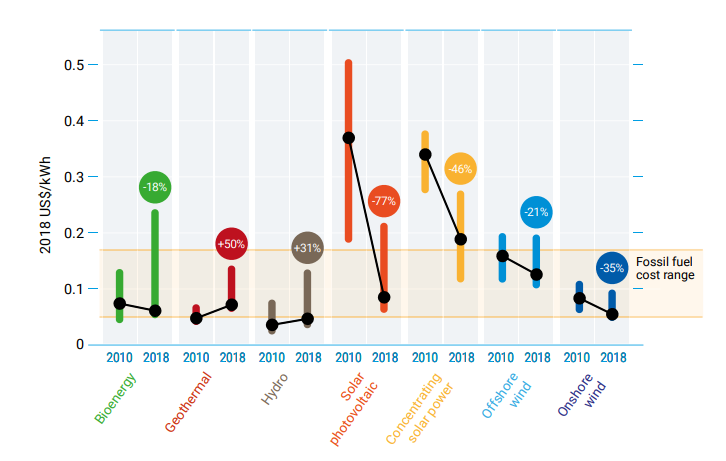

8. Renewables and energy efficiency, together with electrification of end uses, are key to a successful energy transition and to driving down energy-related CO2 emissions.

Given the important role that energy and especially the electricity sector will have to play in any low-carbon transformation, the report examines five transition options, considering their relevance for a wide range of countries, clear co-benefit opportunities and potential to deliver significant emissions reductions. Each of the following transitions correspond to a policy rationale or motivation, which is discussed in more detail in the chapter:

- Expanding Renewable Energy for electrification.

- Phasing out coal for rapid decarbonization of the energy system.

- Decarbonizing transport with a focus on electric mobility.

- Decarbonizing energy-intensive industry.

- Avoiding future emissions while improving energy access.

9. Demand-side material efficiency offers substantial GHG mitigation opportunities that are complementary to those obtained through an energy system transformation.

Material efficiency and substitution strategies affect not only energy demand and emissions during material production, but also potentially the operational energy use of the material products. Analysis of such strategies therefore requires a systems or life cycle perspective. Several investigations of material efficiency have focused on strategies that have little impact on operations, meaning that trade-offs and synergies have been ignored.

Many energy efficiency strategies have implications for the materials used, such as increased insulation demand for buildings or a shift to more energy-intensive materials in the light weighting of vehicles. While these additional material-related emissions are well understood from technology studies, they are often not fully captured in the integrated assessment models that produce scenario results, such as those discussed in this report.

Further to this, the study points out that due to the technology available and the increased understanding of the additional benefits of climate action, in terms of health and the economy, it is possible to reach the 1.5-degree goal by 2030.

What is more, in December 2020, countries are expected to significantly step up their climate commitments at the UN Climate Conference, COP26, which will be held in Glasgow.

Whatsoever, UNEP says that the urgency of the situation means that there is no time to wait one more year and action must be collective and now.

Namely, the Executive Director said that

We need quick wins to reduce emissions as much as possible in 2020, then stronger Nationally Determined Contributions to kick-start the major transformations of economies and societies. We need to catch up on the years in which we procrastinated.

The UNEP chief said that despite the figures, it was possible to prevent the disaster, as the climate procrastination of the past 10 years, is leading to a 7.6% reduction per year in emissions, adding that

Is that possible? Absolutely. Will it take political will? Yes. Will we need to have the private sector lean in? Yes. But the science tells us that we can do this.

Recently, The United Nations Environment Programme’s (UNEP) issued a report assessing countries’ plans and outlooks for fossil fuel production highlighting a significant production gap.

The report in particular, uses publicly available data in order to estimate the difference between what countries are planning and what would be consistent with 1.5°C and 2°C estimates, based on scenarios from the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C.

In 2016 and just one day before the Paris Climate Agreement came into force, the UN Environment Programme released its annual Emissions Gap report revealing that the world is still heading for temperature rise of 2.9 to 3.4oC this century. UNEP says that the world must urgently and dramatically increase its ambition to cut roughly a further quarter off predicted 2030 global greenhouse emissions and have any chance of minimizing dangerous climate change.

The report found that 2030 emissions are expected to reach 54 to 56 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent – far above the level of 42 needed to have a chance of limiting global warming to 2oC this century. One gigatonne is roughly equivalent to the emissions generated by transport in the European Union (including aviation) over a year.

The predicted 2030 emissions will, even if the Paris pledges are fully implemented, place the world on track for a temperature rise of 2.9 to 3.4 degrees this century. Waiting to increase ambition would likely lose the chance to meet the 1.5 oC target, increase carbon-intensive technology lock-in and raise the cost of a global transition to low emissions.

To explore more about the UNEP Emissions Gap Report for 2019, click on the PDF bellow.