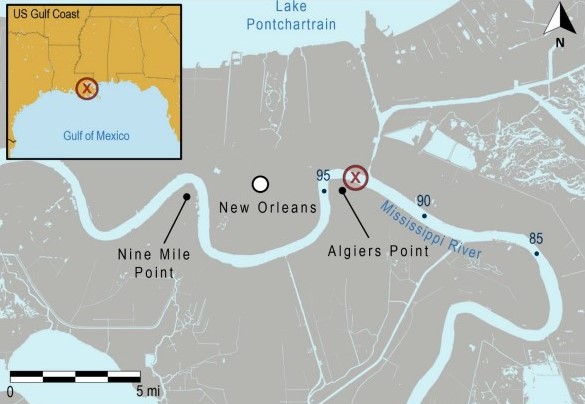

NTSB published its investigation report into the collision of the bulk carrier Jalma Topic, with a barge on the Lower Mississippi River near New Orleans, Louisiana.

The incident

On July 9, 2021, at 1540, after discharging cargo, the Jalma Topic departed the port of Vera Cruz, Mexico, in ballast, with a crew of 19, destined for a grain terminal at mile 117 on the Lower Mississippi River. Two days later, on July 11, beginning at 1020, while the Jalma Topic was under way about 100 miles from the Southwest Pass pilot boarding station, the crew conducted a steering gear test and found no deficiencies with the vessel’s steering or propulsion control systems.

Later that evening, the Jalma Topic arrived at the Southwest Pass pilot boarding station, where an Associated Branch pilot embarked at 1750. Shortly after, the Jalma Topic proceeded northbound through Southwest Pass towards Pilottown, Louisiana (Lower Mississippi River mile 2), where, about 2000, a pilot from the Crescent River Port pilots boarded the ship and relieved the Associated Branch pilot (who then disembarked) to continue the northbound transit towards New Orleans.

On July 12, at 0305, a New Orleans–Baton Rouge Steamship Pilots Association (NOBRA) pilot boarded the Jalma Topic at mile 90.5 to relieve the Crescent River Port pilot. Before disembarking the vessel, the Crescent River pilot told the NOBRA pilot that he had experienced no issues with the vessel during the transit. The NOBRA pilot and the master of the Jalma Topic carried out a master/pilot exchange during which they discussed the vessel’s particulars, handling characteristics, and docking plan. The NOBRA pilot asked the master how many steering pumps were online.

The master told him that there was only one (steering pump no. 1) and the system was not designed to run two simultaneously, but the second pump was in standby mode available for emergency use. The master informed the pilot that the engine room had personnel on watch and a crewmember (the bosun) was on the bow standing by to let go the anchors, if needed. In addition to the master, the second officer (officer of the watch), and a helmsman (steering the ship at the steering stand) were on the bridge.

The vessel proceeded upriver at full ahead order (90 rpm) at a speed of about 9.1 knots. The pilot, standing near the bridge centerline and the portside radar display, discussed matters related to the vessel characteristics with the second officer, who was standing at the starboard electronic chart and information display system console. About 0317, the master stepped off the bridge and went to his cabin one deck below to use the restroom.

At 0320:08 (at mile 92.9), the pilot ordered port 10° rudder, and the helmsman complied. About 17 seconds later, the pilot ordered the rudder to midship, and the helmsman replied to the order and moved the wheel to 0°, but the rudder remained at port 10° on the rudder angle indicator. Eight seconds later, the pilot ordered “steady.”3 The helmsman repeated the order and moved the wheel to steady the vessel, but the rudder did not move. The helmsman told the second officer (in their native language) that the rudder was not responding.

The pilot stated that he saw the bow of the Jalma Topic continue moving to port. At 0320:42, with the vessel at a speed of 9.2 knots with a rate of turn of 15° per minute to port, the pilot shouted, “steady!” immediately followed by “starboard 20,” which he repeated twice. The pilot said he looked up at the rudder angle indicator and saw the rudder was still showing port 10° and it was at that point he knew there was a problem with the steering.

At 0320:46, the helmsman responded to the pilot, “not work,” and immediately after, the pilot shouted, “hard a starboard!” The pilot, who said he went into “emergency mode,” then rapidly ordered hard to starboard, stop engine, and then full astern, in quick succession. An audible alarm (intermittent long-interval buzzer) activated in the background about the same time.

At 0321:09, a second audible alarm sounded (intermittent short-interval buzzer); the second officer later told investigators it was from the steering stand. The second officer told investigators that the only alarm he heard was from the steering stand annunciator unit when he was at the steering stand. He said he “switched off” the alarm before operating the NFU system. He did not recall what the alarm was and said that he had no time to check before moving on to respond to the pilot’s rapid engine orders and anchor-release and whistle-sounding requests.

The second officer went to the steering stand and rotated the helm wheel hard to starboard. He noticed that the rudder was not moving on the rudder angle indicator, so he switched the steering mode from follow-up (FU) mode—with commands inputted at the helm wheel—to non-follow-up (NFU) mode—with commands inputted using an NFU steering lever (tiller). The second officer actuated the NFU steering lever to starboard, which did not have any effect on moving the rudder.

At 0321:17, the second officer sounded the ship’s whistle at the pilot’s request, and it was at this time that the master returned to the bridge. The second officer informed the master the rudder was stuck at port 10°. He then responded to the pilot’s orders of stop engine and full astern by moving to the center bridge console and pushing the propulsion control buttons for stop, dead slow astern, slow astern, all within seconds of each other about 0322.

He later noted that even if they pushed the full astern button, time would be needed for the propulsion to go from full ahead to full astern. The master stated that he recognized the ship was not slowing fast enough, so he called the chief engineer in the engine control room and requested that he emergency stop the engine (as opposed to pushing the emergency stop on the bridge himself), and the chief engineer promptly stopped it.

The master later explained that his request would instantaneously stop the propeller shaft from turning, which would reduce the speed faster than the time needed to reverse the direction of the engine and propeller shaft to operate in full astern.

The Jalma Topic continued turning to port with its rate of turn increasing to 25° per minute, moving towards the right descending bank. Ahead of it, about mile 93.5, was a permanently moored office barge, connected to a work barge by a catwalk, belonging to the Cooper/T Smith Corporation (the location was commonly referred to as Smith’s fleet).

On board the fleet office barge were two dispatchers (one for tugs and the other for a linehandler company), working their 1800–0600 shift on the second level of the office structure, and a cleaner. At Smith’s fleet, an uncrewed deck barge, the Mandy, and three harbor tugs were also moored: the Mardi Gras, manned with a crew of five, was standing by for work, while the Ervin S. Cooper and Angus R. Cooper were not in service and were manned by one duty engineer working between both vessels.

The NOBRA pilot, who had previously worked for the tug company based out of Smith’s fleet, stated that he knew there were people working on the barges and that they were not monitoring the bridge-to-bridge radio frequencies in the area, so at 0320:58, he radioed New Orleans Vessel Traffic Center (VTC) and announced:

Call up Smith’s fleet right away and tell them I’m headed…right in for them; tell ‘em get outta there

While he was making the call, he also ordered the bridge team to “drop starboard anchor.” The pilot then ordered the port anchor let go and for the whistle to again be sounded.

The second officer radioed the bosun on the bow to drop both anchors; he again pushed the whistle button to sound it. The pilot shouted to VTC over the radio:

Tell ‘em to get out of there traffic; right away, get out, get out!

At 0322, New Orleans VTC broadcast a Sécurité message on the traffic frequency, stating the Jalma Topic had lost steering and requesting Smith’s fleet be evacuated.

The two dispatchers aboard the office barge received calls (via phone and handheld radio) from other nearby vessels and New Orleans VTC warning them that there was a ship headed toward the barge so they should evacuate.

As they were attempting to evacuate, the dispatcher for the linehandler company heard the blast of the ship’s whistle. The tug company dispatcher got up from his desk but made it only a “few steps” before the bulbous bow of the Jalma Topic struck the downriver (river side) corner of the office barge at 0322:40, at a speed of 6.2 knots.

Analysis

In the time leading up to and during the loss of steering control, steering control system no. 1 (steering pump no.1 and servo control board no. 1) was in use with FU-1 selected. Before the helmsman noticed that the rudder was stuck at port 10°, there were no indications or alarms on the bridge (or in the engine control room) to indicate a problem to the bridge team: the only alarms were an audible buzzer and flashing lamp from the annunciator unit on the steering stand after the helmsman told the pilot the rudder was not working. The second officer did not check the autopilot data display on the steering stand when he heard it sound and therefore was not aware of the nature of the alarm; after the casualty, investigators found the alarm indicated a servo loop failure.

After the casualty, a technician found the port SSR on servo control board no. 1 had failed and installing a spare SSR resulted in normal operation. Postcasualty troubleshooting efforts identified no problems with the steering system’s power supply, hydraulics, solenoid valves, feedback systems, or the no. 2 system while operational.

Thus, the failure of the port SSR on servo control board no. 1 was the cause of the Jalma Topic’s rudder remaining in a port 10° position (its last ordered position before the failure). Because a failure analysis for the port SSR has not yet been produced, no conclusions can be made regarding how or why the port SSR failed.

There were about 2 minutes from the time the helmsman announced the rudder was not working to when the Jalma Topic struck the office barge, leaving the bridge team with minimal time to identify the problem causing the rudder to be stuck and take appropriate countermeasures, nor was there time to engage emergency steering locally from the steering gear room.

The second officer checked the rudder response in FU mode at the steering stand before switching to NFU mode, which was unsuccessful in moving the rudder. This was because even in NFU mode, with the feedback loop bypassed, the steering signals still had to pass through the same servo control board that contained the failed port SSR. Further, any action to move the mode selector switch from FU-1 to FU-2 while in hand steering would have had no effect in moving the rudder because helm steering signals would have been sent through the servo control board with the failed SSR.

After giving the starboard 20° helm order, the pilot said he saw that the rudder was not responding, and he went into “emergency mode.” He gave orders to minimize or eliminate the headway of the ship towards the bank or barges and tugs as well as signals to alert persons at the site of the incoming danger. The second officer first moved to the steering stand to verify the rudder was not working before activating NFU mode and then moving to address the pilot’s rapid orders (full astern, drop the anchors, and sound the whistle).

The master was not on the bridge initially when the loss of steering control began, and the second officer was the only bridge team officer available to fulfill the requests of the pilot, who was also busy communicating the situation to VTC, requiring him to move to different locations on the bridge. When the master arrived back on the bridge, he had to quickly apprise himself of the situation, after which he told the chief engineer to emergency-stop the engine. The second officer was faced with multiple tasks in response to both the pilot’s rudder and emergency orders.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the contact of the Jalma Topic with the office barge was a loss of steering due to the failure of an electrical solid-state relay on the servo control board of the operating control system to the steering gear. Contributing was the lack of specific procedures available to the bridge team to respond to a failure of the steering control system.

Lessons Learned

Failures in steering control systems can result in damaging consequences. In channels or during maneuvering, where immediate hazards (grounding, traffic, objects) are in proximity and therefore response time is critical to avoiding a casualty, steering system failure contingencies require immediate crew response.

Companies should review and identify potential steering system failures and make quick response procedures readily available to bridge and engine teams. Bridge and engine teams should conduct scenario-based drills to maintain proficiency in implementing these procedures.