According to International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), the International Maritime Organization’s (IMO) 2023 greenhouse gas (GHG) strategy aims for international shipping to reach net-zero GHG emissions by or around 2050.

Hae Jeong Cho, Associate Researcher highlights that LNG is primarily methane, a powerful GHG that leaks throughout the production and combustion processes—including unburned methane that escapes from marine engines, known as methane slip. As a result, a new ship that’s built to sail on LNG instead of conventional fuels can emit more GHGs on a life-cycle basis, depending on the engine technology and how the LNG is produced.

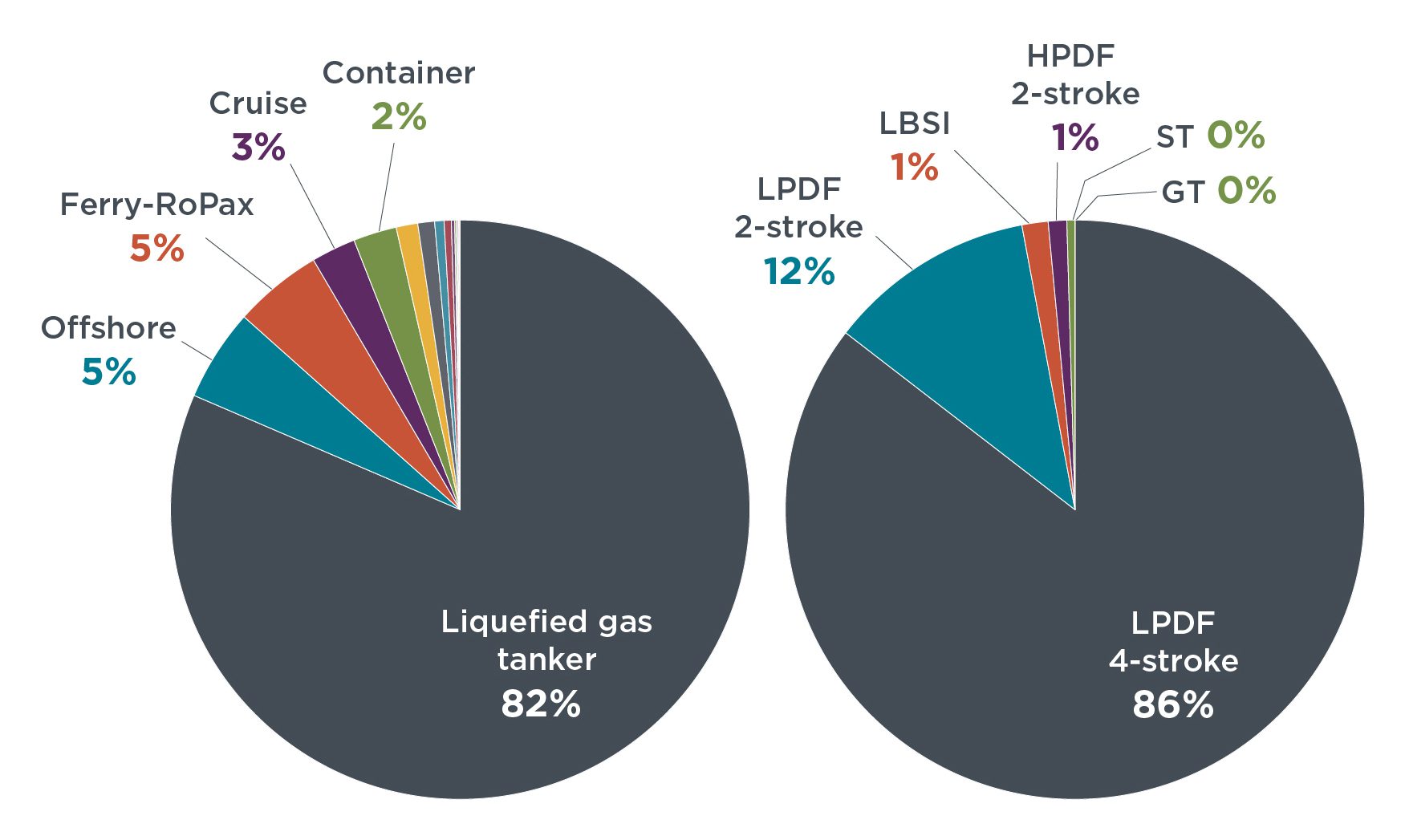

As explained, in terms of engine types, 98% of methane emissions in 2021 came from low-pressure engines, which have much higher methane slip than high-pressure ones. Low-pressure, dual-fuel, four-stroke (LPDF 4-stroke) engines accounted for the lion’s share (86%) and that makes sense: These engines are estimated to have the highest methane slip and have historically been favored by liquefied gas tankers.

Another 12% of methane emissions were from LPDF 2-stroke engines, which have lower, but still substantial, methane slip. Methane emissions from other engine technologies—high-pressure, dual-fuel two-stroke (HPDF 2-stroke), lean-burn spark ignition (LBSI), steam turbines (ST), and gas turbines (GT)—were relatively insignificant.

Furthermore, installations of high-methane-slip LPDF 4-stroke engines are on the rise. More than half of cruise ship capacity by gross tonnage to be built between 2023 and 2025 will run on LNG using these engines, according to IHS Markit (nka S&P Global) data as of July 2023 (the latest available). While a small share of all ships globally, cruise ships have disproportionately high per-ship average emissions because of their hotel and leisure facilities and leaky engines. About the only slightly bright spot here is that the relative share of LPDF 4-stroke engines among engine types in LNG-fueled ships is declining amid growing use of medium-methane-slip LPDF 2-stroke engines that are increasingly used in gas tankers and the low-methane-slip HPDF 2-stroke engines found in most new LNG-fueled container ships and vehicle carriers.

Given that ships can remain in service for decades—the average ship is now more than 22 years old—many of the ships built today will probably still be in the fleet in 2050, when the IMO aims to achieve net-zero emissions. This makes regulations on them crucial, and starting in 2026, the European Union (EU)’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) will cover methane emissions from ships entering or departing EU ports.

A separate regulation, FuelEU maritime, will require ships to reduce the life-cycle GHG intensity of on-board energy use starting in 2025. With the FuelEU maritime regulation in effect, by 2030, ships could only use LPDF 4-stroke engines with 100% fossil LNG if they also use credits from overperforming ships in their fleet or buy credits from other ships; absent that, they will have to use a mix of fossil LNG and qualifying bio- or synthetic fuels. This is because the European Union included methane slip and upstream well-to-tank emissions in the regulations.