A report prepared by UMAS for the Getting to Zero Coalition, called “Closing the Gap“, outlines policy measures that could close the competitiveness gap between fossil fuels and zero-emission alternatives in shipping.

Economic Instruments

According to the report, market-based measures (MBMs) can support the decarbonisation of shipping by closing the competitiveness gap between fossil fuels and zero-emission fuels by increasing the costs of using fossil fuels through setting a price on carbon, and/or reducing the costs of zero-emission alternatives, e.g. through tax breaks, RD&D funds, subsidies, or a combination of these. Additionally, MBMs can also help to mitigate some of the market failures and barriers which are slowing decarbonisation efforts.

The cost of zero-emission fuels must be significantly reduced to close the competitiveness gap with fossil

fuels. To bridge this gap, we need to realize the potential of public-private collaboration

believes Christian M. Ingerslev, CEO of Maersk Tankers.

In addition, a key advantage of taxes/levies and ETS is the potential to generate significant revenues which could be used in different ways to help close the competitiveness gap and/or enable an equitable transition, such as:

- Addressing disproportionately negative impacts on States of GHG reduction measures as stipulated by the Initial IMO GHG Strategy.

- Supporting capacity development, technology transfer, and crew training in developing countries, in particular small island developing States (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs), to facilitate the development and uptake of zero-emission technologies and fuels, and the implementation of maritime climate policies.

- Funding climate projects in developing countries, SIDS and LDCs through existing or new climate finance mechanisms under the UNFCCC or other international organisations.

- Recycling revenues back into the maritime industry to support shipping decarbonisation by subsidising deployment of zero-emission fuels and technologies.

- Offering incentives to ships with lower emissions or carbon intensity compared to a certain benchmark.

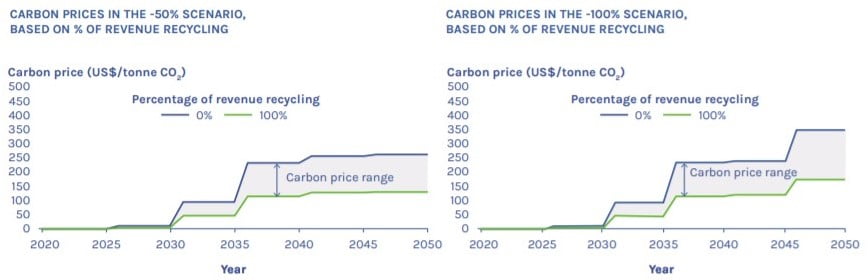

Possible Level of the Carbon Price

In order to achieve 50% GHG emissions reduction by 2050 compared to 2008 (-50% scenario), the carbon price level averages US$173/tonne CO2.

For a 2050 target of full decarbonisation (-100% scenario), the average carbon price would only need to be slightly higher: around US$191/tonne CO2.

In both scenarios, according to the model, the price level begins at US$11/tonne CO2 when introduced in 2025 and is ramped up to around US$100/tonne CO2 in the early 2030s at which point emissions start to decline.

The carbon price then further increases to US$264/tonne CO2 in the -50% scenario, and to US$360/tonne CO2 in the -100% scenario.

Carbon prices could be lower than the model estimates if revenues generated by the MBM are ‘recycled’ to further support decarbonisation of shipping, for example by subsidising the deployment of zero-emission fuels and technologies.

If all MBM revenue was recycled to support shipping decarbonisation, in theory, this could lower the carbon price level by up to half

the report says.

Depending on the level of revenue recycling, an MBM with global scope in the -100% scenario could be designed to have a carbon price level averaging between US$96-191/tonne CO2 and reaching a maximum of between US$179-358/tonne CO2. In reality, the carbon price would likely be somewhere in this range, so that more revenue can be used to enable an equitable transition.

Regulatory Approaches

Direct regulatory approaches, such as the IMO’s energy efficiency regulation (EEDI, EEXI and CII), often called command-and-control measures, could also be employed to close the competitiveness gap and include the following:

- Performance or Emission Standards: Set specific performance goals that must be achieved, but without mandating which technologies or techniques to use to achieve the goal.

- Technology Standards: Mandate which technologies or techniques must be adopted without specifying the overall outcome.

- Product Standards: Define the characteristics of potentially polluting products.

However, one potential shortcoming of standards is that they do not generate revenues, meaning that unless they are accompanied by an appropriate revenue raising, they are restricted in their capacity to enable an equitable transition and address disproportionately negative impacts on States.

Design elements, such as exemptions, differentiation in the standard’s stringency and/or phased implementation of the standard, could be used. However, such design elements could have adverse consequences.

For example, they would lower the environmental effectiveness of the standard, could create loopholes and lead to carbon leakage, but also result in exempted routes being serviced by increasingly old and inefficient ships

the report notes.

Potential Route Forward

There are multiple potential policy options for closing the competitiveness gap between fossil and zero-emission fuels and enabling an effective and equitable transition. One potential route forward is the following policy package:

- Adopt a global MBM capable of generating significant revenue. This mechanism needs to create a carbon price that incentivises emissions reductions and investments into readily available GHG mitigation options in the near term, and fuel switching once alternative zero emission fuels are widely available.

- Combine an MBM with an effective and fair use of revenue recycling and other revenue use options to drive both demand and supply of zero-emission fuels whilst also supporting an equitable transition and addressing disproportionately negative impacts on States.

- Use a direct command-and-control measure such as a fuel mandate in the long term to send an unequivocable signal to the market that a fuel transition will take place.

- Develop national and regional policy that can ensure the transition of domestic fleets at least at the same rate or sooner than international fleets and that work in synergy with global IMO-driven policy.

- Promote voluntary initiatives and information programmes to stimulate supply-side investments in RD&D and infrastructure, encourage knowledge sharing and support capacity development.

This year will be critical for decisions on climate policy in the IMO. Our report shows that there is no single perfect policy and that a successful transition will likely hinge on developing and deploying a mix of policies which can address different aspects of the transition

concludes Dr. Alison Shaw, Research Associate at UCL and co-author of the report.