The US NTSB issued an investigation report on the contact of the towing vessel ‘Lindberg Crosby’ with Interstate 10 Bridge while on San Jacinto River, Texas, in February 2019. The investigation showed that there was an undetected loss of starboard engine directional control due to a separation of the control system mechanical linkage to the pneumatic gear clutch.

The incident

At 1316 local time on 11 February 2019, the towing vessel Lindberg Crosby was with a crew of four, on the San Jacinto River in Channelview, Texas.

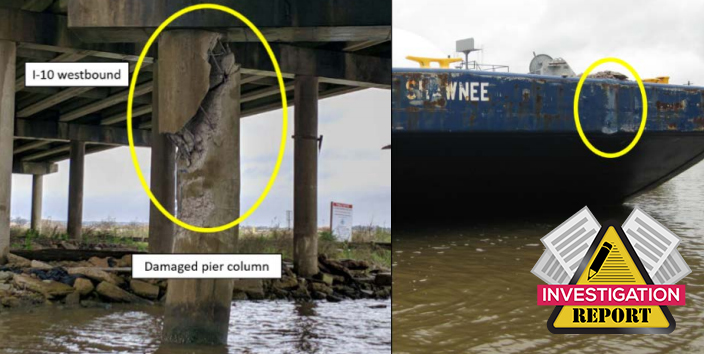

While attempting to dock an empty tank barge at the nearby Southwest Shipyard dock, the vessel suffered a loss of engine control and struck the Interstate 10 (I-10) bridge.

No pollution or injuries were reported. Damage to the bridge and barge was estimated at $1,595,887.

Probable cause

NTSB determines that the probable cause of the towing vessel Lindberg Crosby contacting a pier column of the Interstate 10 bridge was the undetected loss of starboard engine directional control due to a separation of the control system mechanical linkage to the pneumatic gear clutch, resulting in the engine not shifting in response to the operator’s commands.

Analysis

As the vessel approached its intended berth just south of the I-10 Bridge, the captain attempted to slow the vessel by moving the throttles for both engines from ahead to astern.

The port engine shifted astern, but unbeknownst to the captain, the starboard engine remained clutched in the ahead direction.

The result was that the vessel began to veer to port. When the captain attempted to slow the vessel further by pushing the throttles further astern, the port engine responded with increased rpm astern as expected, but the starboard engine continued to push ahead (at higher rpm), which increased the rate of turn to port.

The control loss of the vessel’s starboard engine resulted in the tow’s barge striking a pier column of the bridge.

When the captain examined the starboard engine following the accident, he found that the threaded rod of the actuating piston had disconnected from the connector affixed to the shifting lever.

This prevented any direction changes from being transmitted from the wheelhouse throttle levers to the shifting lever on the transmission, resulting in the transmission remaining stuck in the ahead direction.

With twin propulsion engines and no positive feedback system to alert the operator that shift commands were not followed, the captain did not immediately discern the loss of starboard engine control and discovered it only after observing wheelwash coming from behind the starboard propeller (indicating that it was still pushing ahead).

Although it is unknown how long the pneumatic cylinder had been in operation or how many cycles it had actuated, the stamped numbers on the name plate indicate that the unit was built in 2006 and possibly overhauled in 2014.

Due to the large number of vessels with these types of cylinders in its towing fleet, the operator was unable to provide a date of installation.

Following the accident, the company changed its policy from replacing units that had failed to replacing units at regular time intervals.

As a result of the post-accident tests, the NTSB believes that there was not a material failure of the pneumatic cylinder or its components; the cylinder operated as expected.

The design of the piston within the cylinder allowed it to rotate to account for misalignment in various applications.

Post-accident testing showed that during repeated operation, the piston rod rotated in a direction that would unscrew a threaded connection.

To prevent cylinder shaft rotation as it was fitted on the vessel’s transmission, a jam nut was provided to tighten down against the shift lever threaded connector.

The most likely cause of the separation of the linkage between the cylinder and the transmission lever was the jam nut becoming loose over time, therefore allowing rotation of the piston rod, resulting in the rod unthreading from the shifting lever connector piece.

Lessons learned

Ensuring Jam Nuts and Locking Devices are Secured

Many vessels use mechanical linkages to transmit control commands to critical machinery.

Operators of vessels using adjustable linkages that include jam nuts, locking nuts, or other devices should frequently examine the position of the nuts on shafts to verify their security and develop procedures to effectively ensure critical control system components are included in preventative maintenance programs.

Component and control system manufacturers should provide guidance/options for passively securing jam nuts, such as locking wire, locking washers, securing tabs, thread-locking insert materials, thread-locking fluid, or other means.

Explore more herebelow:

See also: