In its latest Safety Digest, UK MAIB focuses on how a mooring line from a ferry, can easily be tangled in the propeller, without the right communication between the ship personnel and the shore. Based on this accident, MAIB advises to always follow the directions of the safety system and keep in mind that routine operations allow safe practices to be tested.

The incident

A ferry was attempting to leave port, when a mooring line became entangled in propeller.

The ferry had already successfully completed loading, following the order to ‘single up’ from the bridge, and the spring line had been slackened off. When the line became slack, the linesman on the jetty misunderstood this signal and thought to let go. He afterwards removed the line from the mooring bollards and dropped it into the water.

[smlsubform prepend=”GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!” showname=false emailtxt=”” emailholder=”Enter your email address” showsubmit=true submittxt=”Submit” jsthanks=false thankyou=”Thank you for subscribing to our mailing list”]

Minutes later, he walked the line along the jetty, holding onto the attached messenger, and waited for the line to be lifted on board. (see figure 1) As for the ferry on board, the mooring station was not manned to its usual level. The one boatman was on the winch controls and the other one was handling the rope from the drum end.

The senior crewman at the deck,who usually supervised local operations, was still closing watertight doors in preparation for sailing and the third crewman, who should have been involved in line handling, was finishing the cargo lashing.

At the drum end, there was a seaman who had set the line up with three turns on the drum and the remaining tail from the anchorage bitts coiled on a pallet. He then kept the line in his hands facing the pallet and the marine winch and slackened it out, waiting for the seaman’s instructions to stop. But he had heard no orders from the winch operator.

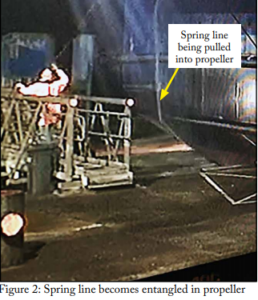

Meanwhile on the pier, the linesman had no idea about the additional slack in the line, as the ship periodically let out an extra line to remove any twists. He kept holding the messenger and waiting for the line to be dragged on board. At that moment, the slack line twisted in the vessel’s propeller (see figure 2), the messenger was hauled from the linesman’s hand and the remaining mooring line was pulled rapidly from the ferry’s deck.

No injuries to the shore or to the cabin crew were reported. The ferry sailed without master’s knowledge that the incident was accursed, and he had to return back to the port station, since there was an intense vibration coming from the tangled rope in the propeller shaft.

Concluding, there was no any damage noticed to the ferry and the divers successfully removed the rope from the propeller. Examinations to establish the circumstances of the episode, indicated that about 10m of slack line had been allowed to enter the water.

Lessons learned

- Both the ferry and the port had safety management systems that detailed safe operations concerning work for berthing and unberthing operations. On this occasion there was no communication between ship and shore, the ferry manning was insufficient and the shore linesman had acted without instruction from the vessel. Safe systems are developed through risk assessment, identifying hazards and implementing risk reduction measures. Taking shortcuts and bypassing safe processes is a sure way to create an accident.

- Routine operations allow safe practices to develop, be implemented and to be tested. However, routine operations can also become hazardous when familiarity and a desire for efficiencies lead to a deviation from safe practice.

- Ship procedures should be realistic and achievable. Where concurrent tasks (watertight preparation, cargo securing and unberthing) are being conducted, it is essential either that sufficient and appropriate manpower is available, or operations are delayed until it is.