A joint research piece by Windward and Sea-Intelligence focuses on overall transit time developments, congestion in Shanghai and what may happen when the port opens fully, plus questions supply chain planners should consider when adapting to this unprecedented situation.

Global Congestion

In January 2022, the ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Oakland were still dealing with the much-discussed congestion crisis that started towards the end of the previous year. According to Windward’s AI-driven insights, the impact of the congestion could be felt by the unusual average length of port calls by container vessels to these ports, which stood at 10.9 days during the first week for 2022, nearly twice the average for 2021.

[smlsubform prepend=”GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!” showname=false emailtxt=”” emailholder=”Enter your email address” showsubmit=true submittxt=”Submit” jsthanks=false thankyou=”Thank you for subscribing to our mailing list”]

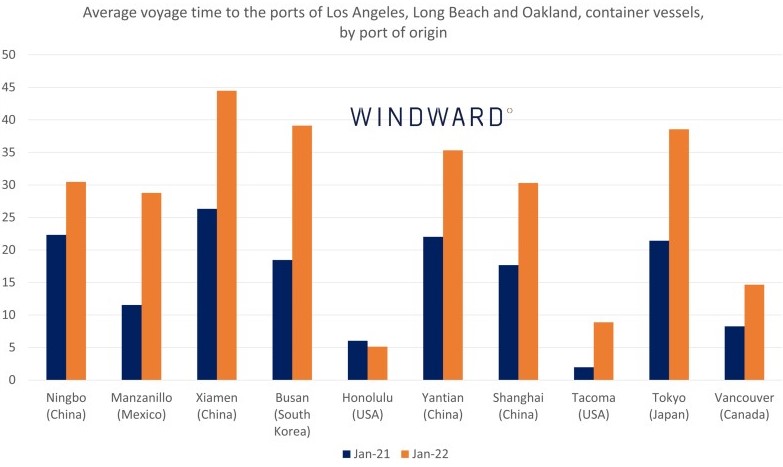

The congestion can be seen more clearly when looking at the transit time to these ports for container vessels from their previous port of call. January 2022 saw an increase of 99% in transit time compared to January 2021, and some voyages experienced a much higher average increase, such as those originating in Tacoma, U.S. (8.9 days vs. 2 days), Manzanillo, Mexico (28.8 days vs. 11.5 days) or Busan, South Korea (29.9 days vs. 18.5 days).

During the week of March 20, immediately after restrictions were lifted in Shenzhen, Windward’s AI-driven insights show a spike of 51.25% in the average length of port calls by container vessels at Yantian port. In April, the average transit time from the previous port of call to berthing at Yantian rose by 98%, compared to April 2021, with container vessels arriving from Taiwan and Vietnam spending an additional 81% and 45%, respectively, on the water, before being able to berth at the port.

On April 5, 2022, Shanghai extended what was a partial lockdown to a full, city-wide lockdown, and has remained tightly restricted since. Interestingly, the picture seems to be quite different in Shanghai, as some voyages required less transit times than in April 2021, such as container vessels arriving from Australia (-41%), Canada (-26%), and from other ports in China (-12% on average for 602 vessels). But there were still hundreds of container vessels that required a considerable amount of additional transit time to berth at Shanghai during April 2022, including over 300 arriving from Taiwan (+34%), South Korea (+25%), Philippines (+25%), and Japan (+17%).

Unprecedented Lows

Data from Sea-Intelligence’s latest Global Liner Performance report show that vessel schedule accuracy, while improving slightly in March 2022, has been declining to unprecedented lows during the period from 2020 to now.

Additionally, carriers have been forced to blank a number of sailings from Asia, often due to congestion in Europe and the U.S. tying up vessels for far longer than planned, resulting in ships being physically unavailable to maintain normal sailings.

Looking at Windward data from April 2022, container vessels sailing towards the Port of Ningbo experienced a rise of 27% in transit time from their previous port of call to a container terminal in Ningbo, compared to the same month in 2021. Container vessels originating from Taiwan had it the worst, with the average length of voyage increasing by 48% that month, followed by those originating from South Korea with a 38% increase, and Japan with a 32% increase.

In addition, Windward data shows that in April 2022, the average length of a port call for container vessels was six hours longer than in April 2021, a 26% increase. Considering there were 828 port calls made to Ningbo by container vessels in April 2022, this represents an additional 4,968 hours that container vessels spent berthing at the port.

The Day After in Shanghai

Filtered for containerships only, the picture is still disturbing, but not quite as dramatic. The fear is massive, prolonged congestion, of course, and various analysis firms have taken stabs at calculating the impact, with estimates ranging from 1 to 2.5 months to clear the port

says Windward.

The above estimates presuppose, however, that everything else in the Shanghai hinterland functions as smoothly as it did prior to the lockdown, and that’s a big assumption.

The port has technically remained open and functional, although it has largely handled prepositioning of empty containers in anticipation of the opening, as well as reefer and a few dry imports. Export containers through the port, on the other hand, have been few indeed, as the rules imposed on truckers bringing those boxes to the port have rendered their operations practically impossible.

It must therefore be assumed that when the port does reopen, it will be mainly for imports of full containers, many of which contain raw materials required for the starved factories in the hinterland to function. Export containers will consist of goods produced before or during the lockdown, but held up in export facilities at the factories, or elsewhere. There is no way of knowing how many containers are, or can already be, stuffed and ready to move, but it is safe to say that the amount is substantial.

But for those export operations to run efficiently, the port must first be drained of a substantial amount of the prepositioned empties, which will take time. Shanghai is now bursting with such containers, and if not cleared or substantially reduced, there may be little room for export loading movements to occur as smoothly as they normally do.