A dedicated Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping (MMMCZCS) working group explores the field of energy efficiency regulations.

According to MMMCZCS, ambitious and clearly defined regulations could significantly reduce CO2 emissions by accelerating the adoption of energy efficiency technology (EET) and operations across the world fleet. However, while the current IMO regulations are well intended, they must overcome challenges to reach their full potential for impact, MMMCZCS finds.

Key recommendations in the report

- Investigate the impact of removing a carbon conversion factor from the measures and focus instead on power or energy units in order to better highlight energy efficiency improvements.

- Address overlaps between energy efficiency measures and upcoming fuel-centric regulations, such as the possible greenhouse gas (GHG) fuel standard and a possible carbon pricing mechanism currently being discussed as part of the mid-term measures.

- Investigate future reduction rates for new EEDI and CII phases.

- Explore opportunities to highlight the role of ports and terminals and ways to regulate all stakeholders influencing the CII rating across the value chain.

- Recommend clear and enforceable mechanisms for CII compliance, possibly including other mechanisms such as the Ship Energy Efficiency Management Plan (SEEMP).

- Evaluate the risk of EEXI and CII compliance via speed reduction, leading to increased overall CO2 emissions due to the need for additional vessels to keep transport work constant.

Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI)

EEDI stands for Energy Efficiency Design Index. It is an index quantifying the amount of carbon dioxide that a ship emits in relation to the goods transported. The actual EEDI of a vessel is called the “attained EEDI” and is calculated based on guidelines published by IMO.

The first phase of the EEDI was impacted by poor market conditions and high bunker costs, which led to the introduction of slow steaming across the industry and thus significantly reduced the installed power needs on board new vessels, MMMCZCS notes and points out that this reduction in installed power made it easy for new designs to comply with EEDI targets.

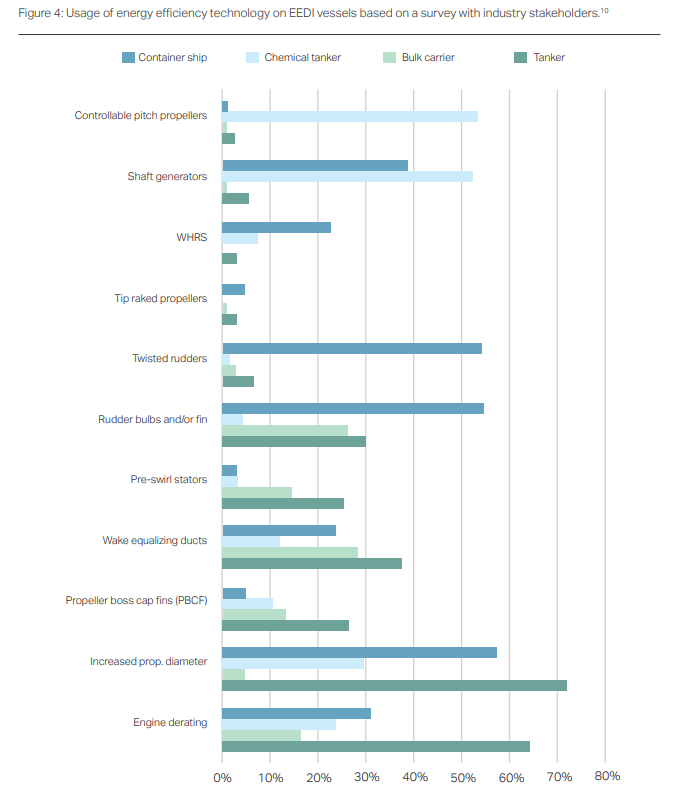

In later phases, the EEDI has proven to be an effective mechanism for promoting the adoption of energy efficiency technical measures. The MMMCZCS study shows that the introduction of dual-fuel vessels during EEDI Phase 2 is blurring the picture on energy efficiency improvements, as a better EEDI rating can be gained using the conversion factor for the fuels the vessel is capable of consuming, thus missing the opportunity for greater energy efficiency improvements.

A ship’s attained EEXI indicates its energy efficiency compared to a baseline. Ships attained EEXI will then be compared to a required Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index based on an applicable reduction factor expressed as a percentage relative to the Energy Efficiency Design Index (EEDI) baseline.

MMMCZCS claims the reduction of available onboard power is unlikely to lead to a short-term reduction of global CO2 emissions, since most vessels routinely operate at speeds requiring even less power than the new reduced power limits. However, in the future, the EEXI will limit the ability of vessels to speed up under favorable commercial conditions or to catch up on schedules due to port delays, the study finds.

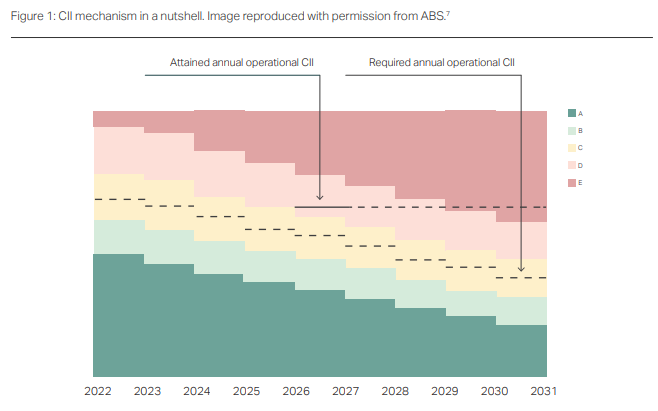

The CII determines the annual reduction factor needed to ensure continuous improvement of a ship’s operational carbon intensity within a specific rating level. The actual annual operational CII achieved must be documented and verified against the required annual operational CII.

According to MMMCZCS, improvements in CII ratings are expected to initially come from operational measures such as speed reduction and vessel deployment changes, with the adoption of technical efficiency measures being limited.

The working group identified several areas where the CII could be strengthened. The current form of the regulations presents a risk that vessels will be able to increase their absolute CO2 emissions while improving or maintaining a given CII rating.

According to the study, this could be achieved by

- sailing longer routes

- lowering speeds

- vessel utilization.

MMMCZCS partners also highlighted some flaws of the annual efficiency ratio (AER) used to calculate the CII. Ideally, a new metric should be more inclusive and more holistically represent how the shipping industry operates.

Furthermore, the CII has a soft enforcement mechanism, creating uncertainty about the benefits and consequences of attaining or failing to attain a given rating.

While the soft enforcement of the CII has raised some questions regarding its ability to reduce global emissions, there seems to be interest from across the industry in achieving compliance and in fully understanding the complexity of this measure, MMMCZCS adds.

In the short term, MMMCZCS expects that the CII could be used as a market tool to drive commercial discussions. It is in this business role, rather than purely regulatory compliance, where MMMCZCS also expects CII to have the biggest impact on reducing short-term emissions.