Andrew Russ, Marine Surveyor at Standard P&I Club, addresses the issue of human element and fatigue in shipping. Mr. Russ reflects on research and measures that aim to resolve this issue, as the human element is a major contributor to accidents in the shipping industry.

Introduction

Investigations into human element incidents, such as the UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB) investigation in 2004 (using data from 1989 to 1999), identified fatigue to be the major contributing factor in 82% of the 66 recorded groundings and collisions occurring between 0000 and 0600 hours.1

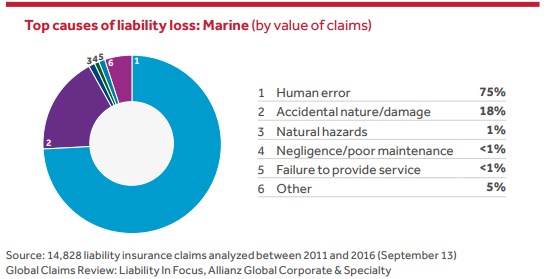

Human error has long been regarded as contributing to the majority of incidents in the shipping sector. It is estimated that 75% to 96% of marine accidents can be attributed to human error. In addition AGCS analysis of almost 15,000 marine liability insurance claims between 2011 and 2016 shows that human error is behind 75% of the value of all claims analysed, equivalent to over $1.6bn. 2

The Karolinska Institute developed the ‘Brief Fatigue Syndrome Scale’ to measure levels of fatigue. This is now used as the industry standard.

Research projects such as Horizon (2012) and Martha (2013-2016) made the most significant advancements in understanding fatigue. In project Horizon, 90 experienced seafarers used simulations of common onboard scenarios. The results clearly showed links between performance degradation and certain work patterns.

Horizon acknowledged that ‘fatigue’ was often used interchangeably with ‘sleepiness’, ‘tiredness’ and ‘drowsiness’, and was considered a generic term. 3

Martha was able to define ‘sleepiness’ and ‘fatigue’ separately:

- ‘Sleepiness – Resulting in short term effects only on daily activities, identified by a rapid onset, short in duration and resultant from a single cause.’ 4

- ‘Fatigue – Resulting in long term effects that may cause health disorders, both physical and mental, has an insidious onset and can persist over time, as a result of multi-factor causes. It is considered to have significant effect on both behaviour and a person’s wellbeing.’ 4

Legislation

Legislation has been introduced to improve the working/living conditions of seafarers, including measures to address fatigue-related issues. International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No.180 adopted in 1996 was an important development in improving safety at sea and implementing limitations on hours of work and rest for vessels whose flag states ratified it. The 2010 Manila amendments to STCW harmonised the requirements of ILO Convention No. 180. STCW allows for ‘overriding operational conditions’ under Regulation VIII/1 – Section B as being defined as ‘essential shipboard work which cannot be delayed for safety or environmental reasons or which could not reasonably have been anticipated at the commencement of the voyage’6. It is paramount that this section of the STCW code is not misused. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

Current legislation has only addressed some of the main factors leading to fatigue. Further amendments are required for it to be truly effective. The main causes of fatigue are: 4

- Prolonged work periods and insufficient rest between work periods;

- Working at times of low alertness;

- Stress and excessive workloads;

- Noise, vibration and motion;

- Duration of crew contracts;

- Pre-existing medical conditions.

Fatigue Risk Management Systems (4)

The introduction of Fatigue Risk Management Systems (FRMS) into the marine industry is anticipated to greatly assist in identifying shortfalls in existing regulations and what amendments could be made to address them. These systems have already had considerable success in other safety critical industries such as aviation, road and rail transportation.

FRMS uses a comprehensive, systematic approach, reviewing all aspects of the workplace including operational requirements/ restrictions, quality assurance as well as company procedures. The standard core elements being implemented across the industry are:

- fatigue awareness training and cultural change programmes;

- a fatigue reporting system within a just culture;

- data-driven analysis for operational fatigue risk assessment, workload management and monitoring of adequate sleep for seafarers.

For FRMS to be truly effective, it will require full commitment from shipowners, shore-side personnel as well as seafarers to report issues and develop tailored approaches for the company.

Potential for improvement

Amendments to operational schedules Operational schedules should be developed taking into consideration seafarers’ and shore personnel’s work and rest hours. This will require shipowners or technical managers to collaborate with charterers and terminal operators. Operations requiring additional crew, whenever practical, should be arranged during times of highest alertness (ideally 1400 to 1800 according to studies) and especially avoiding the 0000 to 0600 period.

Review of ship designs and equipment to further address outstanding issues relating to noise, vibration and motion

Unfortunately, as certain clauses/ appendix of the ‘Code on Noise Levels Onboard Ships’ are considered as recommendations on exempted ships (new builds of under 1,600GRT, certain ship designs and tonnage existing pre-1 July 2014), seafarers’ wellbeing is potentially being compromised for economic considerations. Considering that 87% of the world fleet is older than 1 July 2014 (5) and therefore does not have to comply, it is important that viable economic options for reducing noise levels on older tonnage are found, as well as developments and innovations for new builds. Continual improvements in ship design and operation to reduce levels of vibration and motion on ships are also key elements in improving the overall wellbeing of seafarers and close review of the FRMS results will greatly assist in not only identifying areas in need of improvement but also prioritising them.

Review of safe manning levels

Manning levels on many ships often only meet the flag state minimum for that size and type of ship. Often, this fails to allow for additional watchkeeping requirements whilst sailing through restricted waterways, port operations, non-routine maintenance requirements and/or off duty/overtime work performed by seafarers in order to satisfy commercial pressures, particularly on busy, short-haul trading routes.

It is of paramount importance for shipowners to take the initiative and review their current manning levels. Whilst the minimum manning level is considered the safe lower limit to sail from point A to point B, organisations should consider whether these arrangements are truly adequate in the face of the pressures of the modern maritime industry.

Conclusions

The importance of the human element in shipping must be acknowledged and addressed as it is the major factor in marine incidents, with fatigue as the main root cause. The legislation brought into force to address the factors leading to fatigue have fallen short in reducing/removing these and significant changes in operational practices, ship design as well as manning levels are still required. Research studies and proactive work systems such as FRMS must be embraced and welcomed into the industry and their results acted upon. To move forward will require industry-wide recognition of the issues involved with the human element in incidents and considerable changes in shipowners’/seafarers’ reaction to commercial pressures.

By Andrew Russ, Marine Surveyor, Charles Taylor Mutual Management (Asia) Pte. Limited, Managers of The Standard Club Asia Ltd.

Above article has been initially published in Standard Club’s publication ”Standard Safety” and is reproduced here with author’s kind permission

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of SAFETY4SEA and are for information sharing and discussion purposes only.

Sources

- UK Marine Accident Investigation Branch (MAIB), Investigation report 2004;

- AGCS Safety Shipping Review 2017;

- Project Horizon 2012;

- Project Martha 2013–2016;

- Clarksons Research.

About Andrew Russ

Andrew Russ is Marine Engineer and has 20 years sea experience on various vessel types, working for companies such as Blue Star, Stena, Kuwait Oil Tankers, Vela (Saudi Aramco) & BP. Obtaining the rank of Chief Engineer. He also has 10 years shore experience in various roles in for both Oil Major as well as 3rd Party Manager shipping companies. Andrew has experience in new building projects, dry docking, pre-SIRE/CDI inspections, condition assessment & pre-purchase inspections of Chemical, Crude & Product tankers at varying levels of responsibility. He is also an ISM/ISPS/MLC certificated auditor for Operations & Manning companies for the shipping industry with experience relating predominantly to tanker company assessments. He joined The Standard Club in July 2016

Andrew Russ is Marine Engineer and has 20 years sea experience on various vessel types, working for companies such as Blue Star, Stena, Kuwait Oil Tankers, Vela (Saudi Aramco) & BP. Obtaining the rank of Chief Engineer. He also has 10 years shore experience in various roles in for both Oil Major as well as 3rd Party Manager shipping companies. Andrew has experience in new building projects, dry docking, pre-SIRE/CDI inspections, condition assessment & pre-purchase inspections of Chemical, Crude & Product tankers at varying levels of responsibility. He is also an ISM/ISPS/MLC certificated auditor for Operations & Manning companies for the shipping industry with experience relating predominantly to tanker company assessments. He joined The Standard Club in July 2016

May I get few cases of shipping casualties involving due to FATIGE as case study?