The NTSB released the results of its investigation into the collision of a moving train with the towboat Baxter Southern on the Upper Mississippi in late 2021.

The incident

On November 9, 2021, about 0600, the Baxter Southern departed Spechts Ferry, Iowa, at mile 591, pushing four empty barges downbound on the Upper Mississippi River en route to Donaldsonville, Louisiana. The crew of the Baxter Southern consisted of a captain, pilot, engineer, mate, tankerman, and three deckhands.

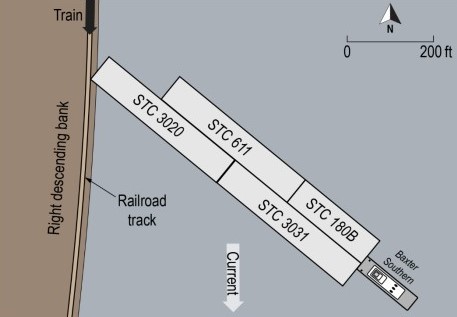

The barges were arranged in two rows. Three of the barges (STC 3020, STC 3031, and STC 611) were 298 feet long, and the fourth barge (STC 180B) was 175 feet long. Overall, the tow was 716 feet long and 108 feet wide. The Baxter Southern used a marine radio as well as cell phones and a computer with satellite internet access to communicate with Southern Towing Company’s dispatcher.

On November 11, the tow moored at the Linwood Dock in Pine Bend, Iowa (mile 475), for fueling. Due to winds exceeding 25 mph, the captain decided to keep the tow there until the winds had decreased to below 10 mph. On November 13 at 0600, the tow proceeded downriver.

About 0900, the BNSF train departed Burlington, Iowa, en route to West Quincy, Missouri, hauling 143 hopper cars loaded with coal. By design, the sides of each locomotive extended about 2 feet from the rails and had a ground clearance of 1 foot. One conductor and one engineer operated the train and monitored its progress from the lead locomotive, BNSF 9251, as the train proceeded on the tracks.

The BNSF train used radio channel 70 to communicate with the BNSF dispatcher in Fort Worth, Texas. The pilot arrived in the wheelhouse at 2245 (the tow was near mile 375), and he and the captain reviewed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration weather website and other weather applications related to area forecasts.

The weather forecast for the area of the Mississippi River through which the Baxter Southern was transiting predicted southwest winds 10–15 mph with gusts up to 40 mph after midnight, changing to northwest winds 15–25 mph with gusts decreasing to 30 mph at noon the following day. The captain stated that he originally planned to tie up at Lock and Dam no. 19 (mile 364) to wait for the wind to decrease, but there were two tows ahead of them, and he knew that those tows would occupy all available mooring space at the lock.

After assessing the forecast, the captain and pilot determined that, with the high winds continuing into the morning, it would be unsafe to proceed to the lock, since there would be no available space to dock or open shoreline for the tow to push up against. They also believed it would be unsafe to try to turn the tow around (top around) and find another place upriver to dock.

The captain and pilot reviewed the vessel’s Rose Point Navigation System, an electronic chart system (ECS), which was set on nighttime display mode. The ECS provided them with detailed electronic navigation chart information for the waterway the vessel was transiting, including depths and widths of the waterway, as well as river mile markers to assist with determining the position of the vessel.

The electronic navigation chart also provided graphical information that could be queried by an operator to view additional information about the waterway. The captain and pilot saw an area marked by magenta dashed line on the electronic navigation chart next to railroad tracks at mile 372, and both said they believed the area represented a fleeting area and that it would be safe to push up against the bank within it.

The electronic navigation chart showed railroad tracks along the riverbank but did not provide the distance from the river to the tracks. The captain told the pilot to head to the marked area on the chart at mile 372 and place the tow up against the riverbank at that location to wait out the weather.

About 2336, the forward port barge, STC 3020, was pushed up on the shore, and the tug and tow were at an approximate 45° angle to the riverbank, with the stern of the Baxter Southern angled downriver. The pilot did not note any problems with the tow pushing up against the shore, and the captain departed the wheelhouse after the head of the tow was on the bank.

About 2338, three crewmembers were mustered and shortly afterward headed forward to verify that the forwardmost barge (STC 3020) was clear of the railroad track. The pilot turned on the vessel’s search light atop the wheelhouse and pointed it toward the bow to illuminate the barges so the crewmembers could see where they were walking.

Before the three crewmembers (who were now on the STC 3020) could check the track clearance, they saw the headlight of the approaching train’s lead locomotive as it appeared to the starboard side of the tow, coming around a slight bend in the tracks behind some trees about 2,000 feet away.

About 2343:51, the left side of the lead locomotive, BNSF 9251, collided with the port corner of the STC 3020’s bow, and the 2-foot overhang of the train impacted the deck of the barge, pushing it into the ground.

Analysis

As the Baxter Southern tow prepared to push up against the riverbank, the captain determined that, due to the nighttime conditions and high wind gusts, it was unsafe to send a lookout forward on the lead barge, STC 3020. Instead, the captain had three crewmembers proceed up to the bow of STC 3020 after the barge was pushed up against the riverbank to determine the location of the barge in relation to the railroad track. Due to the train’s approach within a few minutes of pushing up, the crewmembers did not reach the bow of the STC 3020 before the collision.

After the pilot, who was in the wheelhouse, and the crew of the Baxter Southern, who were out on deck, saw the light of the approaching train as it came into view about 2,000 feet away from the tow, they had about 35 seconds to respond. On the train, the conductor and engineer did not have any indication that the Baxter Southern tow was pushed up against the riverbank before they visually saw the tow about 1,000 feet away.

In addition, they did not realize that the bow of the STC 3020 had encroached on the tracks until the train was about 300 feet from the barge and still traveling about 37 mph. At that point, the train’s engineer activated the train’s emergency brake on the three locomotives and all the hopper cars at 2343:42. After the Baxter Southern’s pilot saw the sparks from the train and realized that the train was not going to be able to stop, he put the tug’s engines in full astern to move the tug and barge away from the riverbank.

However, the engines took 4.5 seconds to respond because of the pneumatic throttle control, delaying the movement of the towing vessel and barges from the riverbank at a time-critical moment. With only seconds to respond, the activation of the train’s emergency brake and the placement of the tug’s engines in full astern occurred too late to avoid the collision.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the collision between the Baxter Southern tow and BNSF coal train was the tow’s pilot and captain not correctly identifying a caution area on the electronic chart before deciding, due to the high wind’s effect on the tow’s empty barges, to push the tow up against the riverbank alongside a railroad track.

Lessons learned

Electronic chart systems (ECS) provide a wealth of navigation information to mariners. Depending on user settings and other conditions, electronic chart display and information systems (ECDIS) can display the same feature(s) differently (compared to paper charts, which display the same information constantly). ECDIS enables users to obtain more information about a feature by querying through a “cursor pick.”

Additionally, there are many features—including warnings and other navigation information—that can be obtained through a cursor pick that are not specifically noted in the default chart display.

Mariners should ensure they understand all symbols and applicable advisories identified in their ECS, and owners and operators should ensure that their crews are proficient in the use of ECS.