NTSB published the accident report of the towing vessel Marquette Warrior, which on November 21, 2021, lost steering after the online electrical generator failed.

The incident

On the morning of November 21, the Marquette Warrior was transiting downbound on the Lower Mississippi River north of Greenville, Mississippi, pushing a 1,000-foot-by-245-foot tow consisting of 35 loaded dry cargo hopper barges arranged five wide and seven long. The barges contained soybeans, beans, rice, and corn to be delivered to several facilities farther south. The crew consisted of a captain, pilot, mate, engineer, cook, two deckhands, and two deckhand trainees. The captain and pilot rotated navigation watches (6 hours on, 6 hours off), with the captain taking the 0500–1100 and 1700–2300 (front) watches, and the pilot taking the 1100-1700 and 2300–0500 (back) watches. According to the crew, the transit was unremarkable, and there were no issues with the vessel’s operation until the time of the casualty.

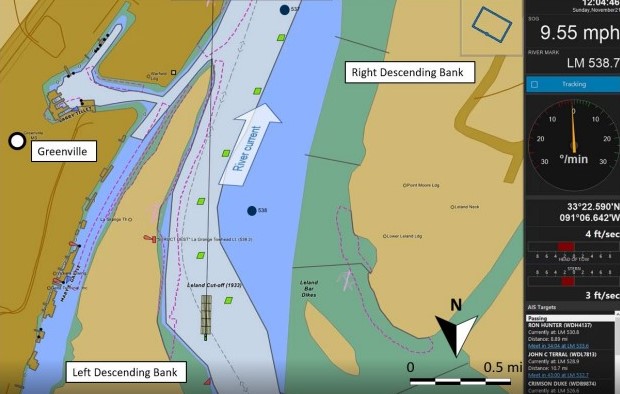

About 1040, the pilot relieved the captain from the navigation watch. At 1150, the vessel and tow passed mile 541 and entered a section of the river known as the Leland Dikes, which stretched for about 3.5 miles down river. The pilot stated the current was a “very swift” 4-5 mph in that area, making navigation challenging. At that time, aided by the river current, the Marquette Warrior was traveling about 10 mph.

About 1200, the vessel’s engineer, who primarily performed engine room preventive maintenance and rounds during the day, returned to the engine room from having lunch in the galley and noticed that the upper engine room lights were flickering. He proceeded to the main switchboard, located in the engine control room, to investigate. He observed a ground fault indication on the switchboard and suspected that the fault might have been the reason for the flickering lighting.

In an effort to determine the cause of the ground fault, the engineer opened several electrical breakers to isolate nonessential equipment. However, the fault did not go away, and the lights continued to flicker. Using the vessel’s intercom system, the engineer then called the pilot in the wheelhouse to inform him of the lighting issue. The engineer also asked the pilot to push up against the riverbank so he could troubleshoot in a safer, controlled condition.

Company

The pilot was still navigating the vessel through the Leland Dikes at 10.5 mph. He informed the engineer that it would be another 25-30 minutes before he could safely push the tow in on a bank and stop the vessel. The pilot then radioed the on-watch deck crew on the barges and requested that they return to the towboat to assist the engineer with troubleshooting and to ensure they were not on the barges in the event of an issue. Immediately after his call with the pilot, the engineer walked forward to the galley to inspect the lighting.

As he arrived in the galley, the lights on “the whole boat started flashing.” The engineer returned to the engine room, where he was met by the mate. The engineer called the wheelhouse again and informed the pilot that he suspected there was an issue with the online (port) electrical generator set (genset) and the vessel needed to stop so he could switch online gensets.

He said he asked the pilot to stop the vessel because he knew that the process to switch online gensets would cause a temporary loss of vessel power. The pilot stated that the tow was still not in an area where they could safely stop.

The vessel was equipped with two gensets that provided power to electrical equipment and lighting on board. Each genset consisted of a diesel engine coupled to and driving a 139-kilowatt Marathon model 431, 3-phase, 480-volt electrical alternator. The 3-phase, 480-volt power produced by the onboard gensets was wired to a main switchboard and then distributed to various electrical equipment and systems on the vessel, such as motorized pumps, fans, and step-down transformers that reduced the voltage to 120 volts to power lighting and lower-voltage circuits.

Each genset was sized to power the entire vessel independently, and the switchboard and electrical bus were configured so that either genset could do so. However, both gensets could not be on the bus together. The process to switch which genset powered the towboat required the engineer to manually start the offline genset, then open the main breaker for the online genset—leaving the vessel momentarily without electrical power.

Once the power to the main bus was interrupted, the running offline (oncoming) genset’s main breaker could be closed, bringing the genset online and supplying the main switchboard (and the vessel) with electrical power.

During normal operations, hydraulic rams moved the Marquette Warrior’s steering rudders. The pressurized hydraulic fluid required to move the rams was supplied by one of two 3-phase, 480-volt electric-motor-driven hydraulic steering pumps. Only one of these motor/pump combinations would run at a time, and they were started and stopped from the wheelhouse or locally at the motor/pump in the engine room from a motor controller panel. If power was lost, the 480-volt electric motors that drove the steering pumps would stop, automatically restarting once power was restored.

About 1205, 5 minutes after the engineer first notified the pilot of an electrical issue, the pilot attempted to initiate a turn to starboard at the La Grange Towhead Light and realized that the rudders were not responding. The pilot immediately radioed the mate, who was with the engineer, and informed them that the vessel had lost steering.

After sounding the general alarm, the pilot attempted to change over the hydraulic steering pumps using a switch in the wheelhouse, but it had no effect. Using the main engine throttles in the wheelhouse, the pilot brought the engines astern to slow the vessel’s speed.

After becoming aware that the vessel had lost steering and still suspecting an issue with the online (port) genset, the engineer began switching over to the starboard genset, a process that he said took “a few minutes.” About 1208, the engineer had successfully switched gensets and informed the pilot. The pilot observed that he had regained steering control. With the vessel traveling at 7.6 mph and still backing down, the pilot, who had been joined in the wheelhouse by the captain, attempted to steer the vessel to starboard around the turn.

About 1210, traveling down river about 5 mph, the forward port barges in the Marquette Warrior’s tow grounded at mile 538 on the left descending bank, and the tow began to push up onto the bank.4 The tow then started to rotate in the current.

The pilot, realizing that the section of navigable river was not wide enough for the tow to rotate around safely, maneuvered the vessel to purposely part the wires holding it to the tow (break the vessel out of tow) and prevent the vessel and tow from being broadside to the swift river current and potentially capsizing. After separating the vessel from the tow, the barges in the tow began to also split from one another.

Analysis

#1 Loss of 3-phase Electrical Power, Loss of Steering, and Grounding: The engineer observed flickering lights and a ground fault indication on the main switchboard, and he attempted to identify and isolate any equipment that might have been causing the fault. Suspecting a potentially serious problem with the electrical system, the engineer appropriately contacted the pilot in the wheelhouse to request he stop the vessel so the engineer could troubleshoot. Given the size of the tow (35 barges), the vessel’s speed (10.5 mph), and location of the tow at the time (Leland Dikes), the pilot was not able to stop the vessel. Thinking of the safety of the deck crew on the barges and that the engineer might need assistance, the pilot called the deck crew back onto the vessel, which likely prevented injuries to crewmembers during the subsequent casualty.

After additional troubleshooting and only 5 minutes after becoming aware of a problem, the engineer identified that there was an issue with the online (port) genset. Knowing that changing over gensets required the vessel to momentarily lose power, he again requested that the pilot stop the vessel. At the same time, the pilot noticed that he had lost steering control. He immediately sounded the general alarm and ordered astern propulsion of both engines to slow the vessel’s speed. Hearing that the vessel had lost steering, the engineer decided to switch online gensets—even though the vessel was not stopped. Within 3 minutes, the vessel regained 3-phase power and steering. Although the engineer resolved the electrical issue by switching gensets and restored steering relatively quickly, the swift current and limited maneuverability of the large tow prevented the pilot from avoiding grounding when the vessel lost its ability to steer while navigating a turn.

#2 Port Alternator Casualty: The Marquette Warrior lost electrical power about 2 weeks before the casualty, when the port genset tripped offline. The onboard engineer investigated the issue, and he identified and replaced a faulty relay within the 12-volt starting circuit. Because this failure was within the 12-volt direct current circuit, it was likely unrelated to the failure of the port genset on the day of the grounding.

Following the grounding, company engineers removed and visually inspected the genset’s Marathon model 431 alternator and then sent it to the company that had recently refurbished the unit for additional inspection and repair. A shipyard electrical supervisor who viewed photos of the damaged alternator after the casualty reported that a ring terminal connection for one of the alternator’s winding leads was burnt and had failed, causing the alternator to lose one of its phases and the steering pump motors (and all other 3-phase equipment) to stop due to a lack of available torque. Electricians from the company that had recently refurbished the alternator also observed the burnt and damaged ring terminal, and in addition they discovered arcing metal residue on three terminal block posts and a severed wiring harness. According to the electricians, this indicated that the wiring harness had been lying across, rubbing against, and eventually arcing to the terminal block posts for a prolonged period. All parties involved agreed that the way the alternator failed would have caused fluctuations in the alternator output voltage and amperage and that the vessel likely would have experienced flickering lights.

The ring terminal connection that was observed to be burnt and damaged following the casualty had been secured to the terminal block post while being refurbished. According to the alternator servicing facility, a lock washer was used to prevent inadvertent loosening of the connection. The electrical alternator unit was then bench-tested satisfactorily. When shipyard electricians later installed the port genset’s alternator in the vessel, there was no need for them to touch the winding leads on the terminal block, as these only needed to be changed if the voltage of the unit was to be altered, something that had already been completed. The shipyard would have only connected the outgoing leads to the terminal block, which did not show signs of failure after the casualty. The unit field tested satisfactorily following shipyard installation. Also, the vessel’s engineer stated that during a recent preventive maintenance inspection of the port genset alternator, he did not need to use a wrench to tighten connections. Because the alternator only had 675 hours (about 28 days) of operating time since being refurbished, it is unlikely that the genset’s winding terminal connection that was burnt and damaged had become loose.

The November 7 preventive maintenance performed by the vessel’s engineer required the removal of the port genset alternator’s cover panel to inspect “all wires/connection” for wire fray, chaffing, and loose connections. Electricians’ analysis of the alternator following the casualty indicated that the most likely cause of the failure was rubbing or chaffing of the sensing wiring harness, which led to arcing between terminal block posts, heat buildup, insulation failure, and eventual winding ring terminal failure. Because the onboard engineer did not notice any damage within the terminal box or to the sensing wiring harness during his inspection, it is likely the chaffing of the wiring harness took place over the 72 hours the genset ran between the November 7 maintenance inspection and the casualty on November 21. While it is possible the wiring harness could have shifted onto the terminal posts due to vessel vibrations, it is more likely that the wiring harness was inadvertently displaced during the vessel engineer’s preventive maintenance inspection on November 7 and went unnoticed during his reinstallation of the cover panel.

Probable Cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determines that the probable cause of the grounding of the towing vessel Marquette Warrior was a loss of steering, likely due to a wiring harness within an electrical generator that was improperly positioned during a maintenance inspection, resulting in the harness contacting the terminal posts, eventually causing the loss of 3-phase electrical power to the steering pump motors.

Lessons learned

Proper operation and maintenance of electrical equipment is required to avoid damage to vessel critical systems and prevent potentially serious crew injuries, particularly for electrical systems with high and medium voltage and equipment with uninsulated and exposed components. Electrical equipment should be installed, serviced, and maintained by qualified personnel familiar with the construction and operation of the equipment and the hazards involved.