NTSB has issued an investigation report into an incident where a tanker struck Naval Weapons Station Pier B on January 14, 2024, while transiting the Cooper River near Joint Base Charleston, South Carolina.

Incident summary

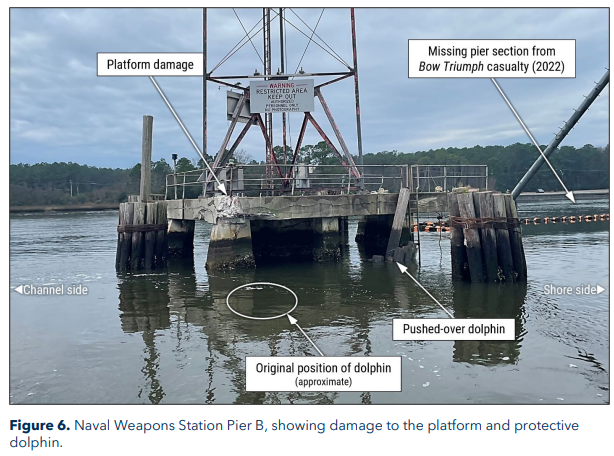

On January 14, 2024, at 1019 local time, the 604-foot-long tanker Hafnia Amessi was transiting outbound on the Cooper River near Naval Weapons Station, Joint Base Charleston, South Carolina, when the vessel struck the Naval Weapons Station Pier B. Hull plating on the vessel’s starboard side, a cement platform on the end of the pier, and a protective dolphin were damaged. There were no injuries, and no pollution was reported. Damage to the vessel and pier was estimated at $8.1 million.

Analysis

On January 14, 2024, about 1019 local time, while the tanker Hafnia Amessi was transiting downbound in the JBC Channel on the Cooper River, the vessel attempted to turn to port when navigating a bend in the river and struck the Joint Base Charleston Naval Weapons Station Pier B. The Hafnia Amessi pilot told investigators that throughout the transit the rudder had responded as ordered, and there were no issues with the vessel’s steering or propulsion. The VDR showed that rudder and engine responses matched the pilot’s orders.

After making a starboard turn at 1010 onto Range D, the Hafnia Amessi pilot began to favor the eastern side of the channel as the vessel approached the port turn (bend) on Range C. According to the pilot, he did this because he expected the ship would be set toward the outside (western side) of the bend by the flood current on Range C. However, the pilot stated that during the approach to the turn, the tanker moved toward the east bank more than he had planned for or anticipated. Winds were off the Hafnia Amessi’s starboard side at 8 knots while the vessel was on Range D. Transiting in ballast, the vessel had a greater freeboard and therefore a large surface area for the wind to act on. Although not strong, the winds may have contributed to the Hafnia Amessi’s movement toward the east bank.

When the Hafnia Amessi moved toward the east bank, the vessel approached Shoal 4 and was susceptible to bank effect. Bank effect is experienced by ships maneuvering in confined waters (e.g., close to a canal bank, riverbank, or shoal). While a vessel is making headway, water pushed ahead of and flowing down the side of the ship creates positive pressure forward of the pivot point and negative pressure aft. In a channel, the resultant forces can yaw a ship’s bow away from the bank (bank cushion) while attracting its stern toward the bank (bank suction). Though bank effect is often experienced in waterways with steeply sided banks, The Shiphandler’s Guide explains: “To a ship running in shallow water, with adjacent but gently shelving mud or sand banks, such as low-lying estuarial areas … the effect can be far more insidious and violent.” Generally, the faster the ship sails, the greater the suction at the stern.

As the Hafnia Amessi transited along the east side of the channel, the vessel traversed a section where shoaling had reduced the depth significantly. Between 1015:24 and 1017:28, the tanker’s recorded UKC reduced from 30 feet to 9.8 feet. Given the slope of the channel bank, the clearance under the hull at the turn of the bilge on the vessel’s port side was likely shallower than the recorded UKC. At the same time the pilot was attempting to turn the Hafnia Amessi to port, the bank effect forces worked against the turn by pushing the bow away from the bank (to starboard) and pulling the stern toward the bank (to port).

In addition to bank effect, the Hafnia Amessi would have also been affected by the flood current when the vessel rounded the turn onto Range C. As the tanker’s bow emerged from the shadow of the east bank, the current would have acted on the submerged portion of the vessel’s port bow—pushing it away from the bank and further working against the attempted port turn. The predicted current at Snow Point, just upriver of the turn, was 1.2 knots. Actual currents can vary from predicted currents based on factors such as downstream storm surges and upstream waterflow.

As the Hafnia Amessi passed buoy 80 upstream of Pier B, it experienced “an exceptional amount of tidal current,” according to the pilot, which reduced the vessel’s speed to less than 5 knots—4 knots slower than its rated speed at slow-ahead. The pilot said, “In all my years working down here, I’ve never seen a wake on a buoy at that location to be so strong.” Based on his observations, it is likely that the current in the JBC Channel exceeded the predicted tidal current, further impacting the Hafnia Amessi’s ability to maneuver through the turn.

In 2022, the Bow Triumph experienced bank effect and current forces, which the pilot’s rudder and engine orders could not overcome, resulting in contact with Pier B. Similar to the Bow Triumph casualty, the Hafnia Amessi pilot’s rudder and engine orders could not overcome the bank effect and current forces acting on the tanker, resulting in the vessel’s contact with the same pier.

The silting of the Cooper River on the eastern bank at Shoal 4 was a known hazard, and almost all the tank vessels of similar size that transited downbound through the bend in the 3 years before the Hafnia Amessi casualty approached via the center or western side of the channel. Vessels that approached the bend in this manner navigated through the turn without incident. The TRF Mandal, the Bow Triumph, and the Hafnia Amessi were the three exceptions, transiting on the eastern side of the channel as they approached the bend. Only the TRF Mandal negotiated the turn without incident, although it finished the turn wider (more to the outside/western side of the channel) than any other tank vessel that successfully navigated through the bend.

The TRF Mandal—a sister vessel of the Hafnia Amessi (same design, length, and breadth; nearly the same tonnage)—had the same pilot aboard (as the Hafnia Amessi), and, when he piloted the TRF Mandal, he followed a similar route near the east bank. Various factors may account for the different outcomes between the TRF Mandal and Hafnia Amessi transits. The TRF Mandal entered the turn at a speed over ground 1.6 knots less than the Hafnia Amessi. Additionally, the predicted current at the time of the TRF Mandal transit was about 0.2 knots slower than the current during the Hafnia Amessi transit. Consequently, the difference between the TRF Mandal’s and Hafnia Amessi’s speeds through the water was even greater than the difference in speeds over ground. Also, according to AIS data, the TRF Mandal transited farther from the riverbank than the Hafnia Amessi.

According to research on hydrodynamic forces in narrow channels, at low speeds, the yawing moment on a vessel caused by bank effect varies at roughly the square of a vessel’s speed (S2) in a deep channel. In waters where the ratio of depth to draft is less (shallower), the yawing moment increases as a function of speed to a power that may exceed 5 (S5+). Additionally, the magnitude of the forces and moments acting on a ship increase with decreasing distance off the bank. Therefore, the differences in speed, current flow, and distance from the bank between the TRF Mandal and Hafnia Amessi transits, while small, would have had a significant effect on each vessel’s maneuverability. Although the TRF Mandal successfully navigated the turn, the Bow Triumph and Hafnia Amessi casualties demonstrate that transiting in the center of the channel is prudent to avoid the risks associated with bank effect and current. If the Hafnia Amessi had approached the turn onto Range C in the relatively open water to starboard, the bank effect on the vessel’s port side would have been minimized, and the vessel would have been better positioned to handle the oncoming flood current.

To prepare for the Hafnia Amessi’s transit, the pilot ordered the tugboat Diane Moran to escort the tanker down the Cooper River. The pilot stated that this order was a direct consequence of what he had learned from studying the Bow Triumph casualty. When it became apparent that the Hafnia Amessi was not responding to rudder and engine orders as the pilot anticipated and was in danger of striking Pier B, the pilot directed the Diane Moran to push on the tanker’s bow. According to the pilot, the ship’s rate of turn did not increase until the tugboat began pushing. The Diane Moran pushed on the bow until it became too dangerous for the tugboat to remain in position without hitting the pier itself. The Hafnia Amessi contacted the end of the pier on its starboard side, but due to the turn induced by the tugboat, damage to both the pier and ship was considerably less than the damage caused by the Bow Triumph casualty. The Diane Moran captain’s quick response to the pilot’s orders and his skilled maneuvering of the tugboat prevented a more serious casualty.

Conclusions

Probable cause

The National Transportation Safety Board determined that the probable cause of the tanker Hafnia Amessi’s contact with Naval Weapons Station Pier B was the pilot navigating too close to the east bank before the turn, exposing the vessel to bank effect that rudder and engine orders could not overcome.

Lessons learned: Planning for hydrodynamic forces in areas subject to shoaling

Hydrodynamic forces such as squat, shallow water effect, and bank effect can reduce rudder effectiveness and unpredictably alter a vessel’s course. Shoaling can decrease channel depth below charted expectations, worsening these effects. Even experienced pilots may find it challenging to manage these forces. When planning transits in shoaling-prone areas, pilots, masters, and operators should assess the risks and consider mitigation strategies such as tug assistance, adjusting speed, or delaying transit until conditions improve.