The International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) has released a report analyzing the reduction in the global average GHG fuel intensity (GFI) and the operational efficiency improvements that would be necessary for the IMO to achieve its climate goals.

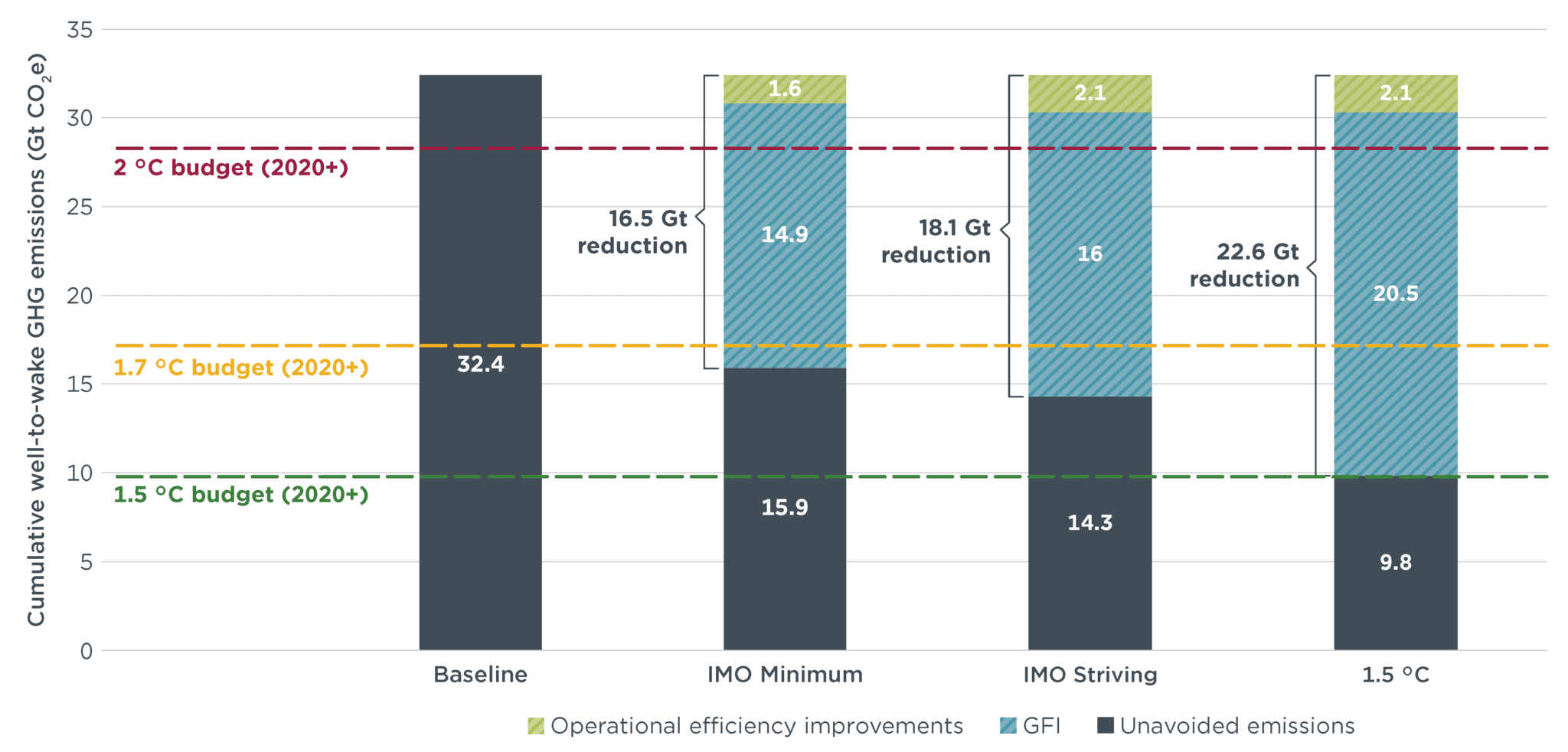

The ICCT study takes three decarbonization scenarios and estimates cumulative emissions from 2020 to 2050 and compares them with shipping’s proportional share of global carbon budgets for 1.5 °C, 1.7 °C, and 2°C warming scenarios.

- IMO Minimum: The GHG emissions from international shipping decline by 20% by 2030 and 70% by 2040 compared with 2008 emission levels, and the sector achieves net-zero emissions by 2050.

- IMO Striving: The GHG emissions from international shipping decline by 30% by 2030 and 80% by 2040 compared with 2008 emission levels, and the sector achieves net-zero emissions by 2050.

- 1.5 °C: Cumulative GHG emissions from international shipping are below the shipping sector’s proportional share of the carbon budget that aligns with a 67% chance of limiting warming to 1.5 °C.

Key findings of the analysis

ICCT analysis found that the global shipping sector is on a trajectory to exhaust its proportional 1.5 °C carbon budget by 2030, its 1.7 °C budget by 2037, and its 2 °C budget by 2047. Mid-term measures aligned with the targets in the IMO Minimum or IMO Striving scenarios could achieve cumulative emissions that are consistent with limiting warming to 1.7 °C.

Projected operational efficiency improvements resulting from the IMO mid-term measures could reduce cumulative emissions by about 10% between 2020 and 2050. The remaining 90% will require replacing fossil fuels with net-zero GHG fuels or energy on a life-cycle basis, which can only be achieved by advanced technologies that have not yet been fully commercialized.

Furthermore, reducing the global average GHG fuel intensity (GFI) using the Global Fuel Standard (GFS) would require that the regulation, and the guidelines used to implement it, accurately account for the well-to-tank and tank-to-wake GHG emissions of marine fuels and prevent the use of food- and feedbased biofuels. It would also require an unprecedented level of financial investment in the nascent and pre-commercial technologies necessary to produce genuinely zero-carbon fuels.

If the real-world well-to-wake GHG intensity of the fuel mix used to satisfy the GFS requirements is not accurately accounted for, then the life-cycle GHG emissions from shipping will be higher than implied by the policy.

To bridge this gap, regional and national governments would need to implement their own policies to regulate the GHG intensity of the fuels ships use on voyages to, from, or between their ports. These policies would need to be considerably more ambitious than current international best practices, as contained in the FuelEU Maritime regulation.

Zero emission fuel requirements

About 90% of the emission reductions would need to come from zero or near-zero GHG emission energy sources that meet the GFI requirements. Examples would include ammonia produced using 100% renewable electricity that is additional (i.e., not diverted from existing uses) via electrolysis with strictly controlled N2O emissions, or methanol produced either using captured carbon and 100% additional renewable electricity via electrolysis or using biogas made from wastes and residues.

Biofuels with high ILUC emissions, such as those made from food and feed feedstocks, might have lower direct GHG intensities but higher life-cycle GHG intensities than the fossil fuels currently being used in the shipping sector because of those land-use change emissions.

In the IMO Minimum scenario, the GFI-only pathway needs to achieve a 30% reduction in the GFI by 2030 compared with the 2019 level to achieve a 20% reduction in total GHG emissions by 2030. This also implies that zero-emission fuel would need to account for 30% of total energy consumption by 2030. With efficiency improvements, the required share of zero-emission fuel by 2030 would fall to 22%. I

Moreover, in the IMO Striving scenario, the required share of zero-emission fuel would be 39% without efficiency improvements and 30% with efficiency improvements. Finally, to align with 1.5 °C, the share would need to be 54% in 2030 and 100% from 2038 onward.

One of the ambitions in the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy is to increase the uptake of zero or near-zero GHG emission technologies, fuels, and energy sources to at least 5% (striving for 10%) of the energy used by international shipping by 2030. ICCT results however, imply that even the 10% target would not be enough to meet the 2030 emissions target from the IMO Minimum scenario.

While GFI reduction requirements under the two compliance pathways converge over time, efficiency improvements reduce the total energy consumption of international shipping and the amount of zero-emission fuels needed each year through 2050.

These improvements allow international shipping to achieve the IMO Striving scenario target with less zero-emission fuel (shown by the solid blue line) than is required to achieve the IMO Minimum scenario target with only GFI (shown by the dashed yellow line).

These improvements allow international shipping to achieve the IMO Striving scenario target with less zero-emission fuel (shown by the solid blue line) than is required to achieve the IMO Minimum scenario target with only GFI (shown by the dashed yellow line).

The results of the study indicate that achieving the IMO’s GHG emission reduction targets will necessitate unprecedented ambition in GFS requirements and economic measures that ensure an effective carbon price signal.

In addition, these mid-term measures should promote the use of scalable zero-emission fuels that can bring meaningful climate benefits: renewable hydrogen-based e-fuels. The findings underscore the urgency of finalizing and implementing these policies to align shipping with global climate goals.