During the SAFETY4SEA Hamburg Forum 2024, Gavin Allwright, Secretary General, International Windship Association (IWSA), provided a comprehensive exploration of wind propulsion and its crucial role in reducing shipping emissions.

MEPC 80 – Decarbonisation strategy

Our emission reduction targets are ambitious: aiming for a 20% reduction by 2030 (striving for 30%), measured against a baseline year of 2008. Acknowledging that 2008 represented a notably high emissions level, we recognize that our current emissions exceed this benchmark.

Looking ahead to 2040, our objective is even more substantial—a reduction of 70% (striving for 80%) in emissions. Ultimately, we aim to achieve Net Zero emissions by 2050, although I personally find the concept of “net zero” complex.

Initially, the IMOstrategy focused on fuel-based solutions, aiming for 5% of zero-emissions fuel adoption by 2030 (striving for 10%). However, this perspective has shifted to focus on energy and the technologies that harness it. Wind propulsion emerges as a standout solution—a pure zero-emissions energy source, not solely greenhouse gas emissions. Wind energy itself generates no emissions of any kind, although the technologies used to harness that for propulsion do have have minimal emissions.

There is a big realization that we have to be moving a hell of a lot quicker on the things that we already have available off the shelf.

Direct application of wind power

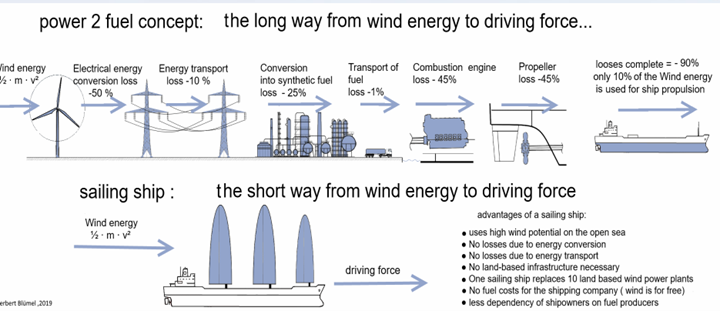

Imagine this: when you deliver units of power to a wind turbine and then use that power to produce fuels which are subsequently burned and used to propel a vessel, you may only get about one or possibly two units of energy out for propulsion. In contrast, wind propulsion is direct and efficient, with 10 units of energy input resulting in 10 units of propulsion output.

Over the last 100 years, we’ve heavily relied on fossil fuels, but now we’re talking about zero emissions and zero cost. Wind energy itself is free—it’s delivered directly to the vessel at the point of use without the need for mining, refining, transporting, bunkering, or storing it onboard.

With wind propulsion, there’s no need for additional infrastructure, and the price of wind energy is stable and predictable at zero.

Sometimes there is volatility in wind conditions, particularly when the wind is not consistently blowing. People often approach me with the notion that sometimes the wind does not blow, which is a valid consideration. In wind-assisted vessels, the propulsive energy contribution from wind can range from 5% to 20%, potentially reaching up to 30% when averaged out. However, with optimization in mind, particularly in the design phase of new vessels focusing on wind as the primary source of propulsion, energy contributions from wind can reach much higher percentages—50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, and even 90% on certain routes. There are even projects underway exploring the concept of climate-positive ships that generate more energy than they consume, storing excess energy onboard in the form of hydrogen.

This potential paradigm shift towards wind propulsion must be acknowledged alongside the fact that wind propulsion technologies are not without costs. Although there is zero development time required as thirteen different options are already available on the market today, it’s important to note that these technologies are not free. The advantage lies in their compatibility; whether opting for wind-assisted ships with ammonia, methanol, or other fuel combinations, there are no compatibility issues to contend with.

These wind propulsion systems require zero additional crew due to their high level of automation, and if a leasing system or ‘pay-as-you-save’ finance model was adopted there could be a near zero capital expenditure required upfront. Most systems are deck-installed that can lend themselves to a leasing model, with one of our members already having signed an agreement with Mizuho Banking Group to offer leasing options. The cost is covered by the fuel savings achieved, meaning there’s no initial expense or only a limited one.

We conducted a survey within the industry and among policymakers, including wind propulsion as one of five options, to gauge the projected energy mix for 2030 and 2050. Typically, such surveys overlook wind propulsion, considering it merely as an energy efficiency measure rather than a significant propulsion solution. However, when wind propulsion was included, the response was overwhelmingly positive, with expectations of stronger adoption by 2030 for wind-assist systems and a surge in newly designed ships with primary wind propulsion by 2050, though these results aren’t definitive they are indicative of a transition pathway that is becoming increasingly attractive to the industry.

Currently, we have approximately 36 installations with four more expected this month and another scheduled for next week. Additionally, we have 12 vessels that are wind-ready, meaning foundational work and radar adjustments have been completed, with installations likely to follow later this year or beyond. We anticipated doubling our installations over the past year, and that was achieved, with a similar growth trajectory expected next year. Extrapolating further, the EU has forecasted between 3,700 and 10,700 installations by 2030, although this was forecast before 2018 and the initial IMO decarbonization strategy. The UK government has gone even further, predicting that 40% to 45% of the global fleet will incorporate some form of wind propulsion by 2050. We believe both these estimates are conservative.

The views presented are only those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of SAFETY4SEA and are for information sharing and discussion purposes only.

Above article is a transcript from Gavin Allwright’s presentation during the 2024 SAFETY4SEA Hamburg Forum with minor edits for clarification purposes.

Explore more by watching the video presentation here below