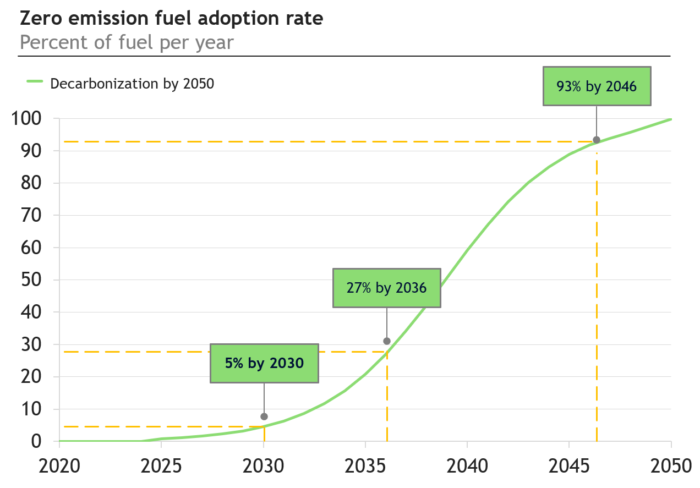

A study conducted by UMAS for Getting to Zero Coalition suggests that zero emission fuels need to make up 5% of the international shipping fuel mix by 2030, in order to enable decarbonization in line with Paris Agreement goals.

The ambition of the Getting to Zero Coalition is to have commercially viable zero emission vessels operating along deep sea trade routes by 2030. In 2019, UMAS conducted a study to describe the most technologically feasible paths to achieving decarbonization for international shipping by 2050 – which would put the sector in line with a 1.5C trajectory in line with Paris Agreement – and by 2070 – the IMO aligned trajectory. In both cases, zero emission fuels needed to make up 27% of energy by 2036.

A new insight briefing by Getting to Zero Coalition suggests that a quantified target for “commercially viable” zero emission ships by 2030 would help mobilize commitment and action across stakeholders, as:

- Energy companies would have greater confidence in demand when planning green fuel development projects,

- Cargo owners could be mobilized to pay a premium for zero emission fuels on a corresponding percent of their freight,

- Investors could quantify the amount of investment needed across the value chain,

- Ship owners could plan investments in new builds and retrofits, and

- Regulators could be called on to ensure a level playing field is in place to enable the transition.

How can the 5% target be reached?

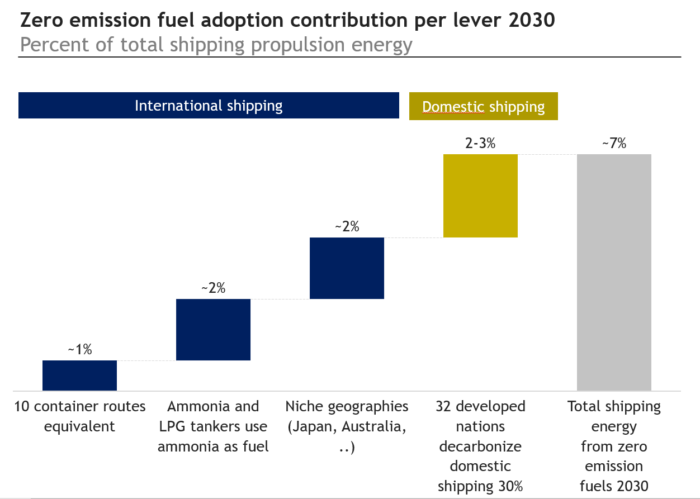

There are three primary subsegments of shipping that could move first and achieve this 5% target:

- Container shipping is likely the first shipping sector to start to decarbonize as a few ports/routes account for a large share of volume, and the sector is closer to the end consumer. For example, 10 large deep-sea routes accounted for 7 million tons of CO2 in 2018. These 10 routes could make up 0.8% of the total 5% needed.

- If ammonia is selected, ammonia and LPG tankers are well suited to be first movers, as storage, systems and crew are well adapted to this fuel. This is also true for ships used to transport other hydrogen-derived fuels. Ammonia transport alone accounted for approximately 0.1% of emissions in 2018. Together with LPG tankers, the sum could be 2% of the total 5% needed. This is an upper bound and would require high rates of transport demand growth.

- Niche international routes (non-container shipping) with high likelihood of having enabling conditions for first movers of zero emission fuels – for example Chile-US, Japan-Australia, Dubai-Singapore, Australia-Singapore, Denmark-Norway – could provide another 2%.

In addition, domestic shipping could account for another 2-3%. 32 developed nations make up approximately 50% of domestic shipping emissions.

If they achieve 30% of energy from zero emission sources, this would correspond to 15% of domestic shipping energy and 2-3% of total shipping energy. Therefore the UN Climate Champions have set 15% of zero emission fuels by 2030 as the Breakthrough necessary for domestic shipping.

To reach the right quantity and price of green hydrogen, several other actions are needed to boost zero emission fuels by 2030. For example, large scale system demonstrations are needed to showcase feasibility and draw conclusions.

Freight purchasers can also give important demand signals by committing to use zero emission fuels where available at a certain premium.

The need for a rapid deployment of capital and low cost long-term investments requires institutional investors and IMO regulation in line with Paris targets focusing both on operational efficiency measures and on incentives to adopt zero emission fuels.

In conclusion, a quantified target for zero emission fuel adoption by 2030 would help mobilize action from industry stakeholders. To enable decarbonization of international shipping by 2050 (1.5C aligned), zero carbon fuels will need to account for approximately 5% of the fuel mix by 2030.

Even if the target is a 50% absolute reduction by 2050, this still requires rapid growth of zero carbon fuel use in the 2030s, which requires a similarly small initial use by 2030. Achieving this is feasible on all counts – with regards to fuel supply, vessel technology, port infrastructure, safety, demand, government commitment and finance

…the Coalition notes.