”As we continue the journey towards a more sustainable future, it is not a question of when, but rather how we will achieve the required transition.” says Nick Brown, Chief Executive Officer, Lloyd’s Register, in the Global Maritime Trends 2050 report, published by Lloyd’s Register, which describes future landscapes and thought-provoking ‘What If’ scenarios for the maritime industry for the coming years.

The report analyzes industry’s trends and combines these in varying ways to create very different futures for the maritime sector. In particular, considering that climate change and decarbonisation are set to be defining challenges for the coming decades, the trends are categorized across two axes: the nature of global co-operation on the climate agenda and the speed of technology uptake.

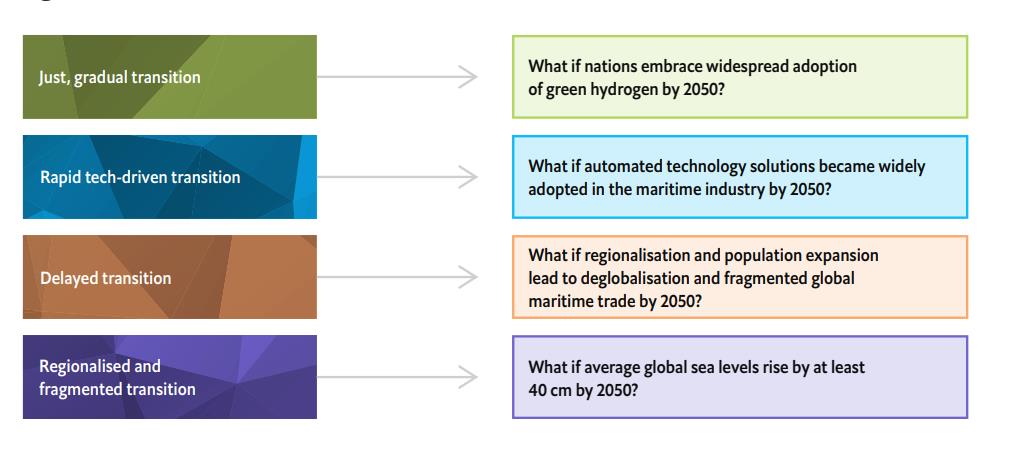

Across these two axes, the following four futures have been identified:

1. Just, gradual transition: high global cooperation combined with a gradual uptake of novel and/or advanced technology.

2. Rapid, tech-driven transition: high global co-operation combined with a rapid uptake of novel and/or advanced technology.

3. Regionalised and fragmented transition: high global fragmentation combined with a rapid uptake of novel and/or advanced technology.

4. Delayed transition: high global fragmentation combined with a slow uptake of novel and/or advanced technology.

The 4 future scenarios for industry’s transition

#1 Just, gradual transition

A just, gradual transition sees high levels of global co-operation combined with the gradual but regulated integration of novel technologies. It encompasses broader discussions on what the maritime sector needs to do to decarbonise successfully and equitably.

This transition in the maritime sector will be guided by an intergovernmental agreement that successfully limits global warming to 1.5 degrees by 2050 and paves the way for the integration of novel technologies.

As such, there will be different sets of fuels used in 2050 that will require different systems such as engines, fuel supply systems, fuel tanks and bunkering infrastructures. Also, the needs of training and hiring onboard crews for operating new different systems will be increased.

In this future, technology integration will take place gradually: reflecting some of the difficulties associated with reaching global consensus, distributing the benefits, and ensuring that policy, investments, and health and safety standards progress at a steady pace.

#2 Rapid, tech-driven transition

High levels of global co-operation may also be accompanied by rapid integration of novel technologies across the maritime sector. This

future—a rapid, tech-driven transition—would see automated solutions, smart technologies, fuel and system efficiencies, and higher levels of data sharing.

The assumption in this future is that global co-operation on decarbonisation will mandate the rapid roll-out of novel technologies through high investments, economic incentives and favourable policies that can keep up with the pace of industry innovations.

The rapid uptake of technology, if done collaboratively, could also mean that maritime jobs are better protected.

But this future is not without its risks, the main one being cybersecurity. Increasing the autonomy of vessels opens up massive risks around cybersecurity and the potential to cause very serious disruption. Not only in vessels, but also port operations. So, although it’s a good thing in terms of efficiency, we need to be adopting very different risk assessment processes to deal with this.

#3 Regionalised and fragmented transition

A regionalised and fragmented transition would combine low levels of co-operation with the rapid integration of technology.

The assumption here is that countries may be unable to co-operate on decarbonisation— whether due to geopolitical or economic priority differences—and, in turn, will rely on the rapid integration of technology to unilaterally meet national climate objectives and adapt quickly to growing climate challenges. As such, the rates of technological integration will vary by country, as the absence of co-operation will mean that technological adoption depends on financial and technical capacity.

The risk here is that poorer economies will be left behind, exacerbating economic inequalities. Another is that technologies are deployed without careful consideration and preparation. Given the latter, the risks of cyber attacks in this future are particularly high.

Limited cooperation, restricted data sharing and high intergovernmental tensions may leave roomfor more bad actors to operate with limited oversight.

#4 Delayed transition

A delayed transition describes a future where global co-operation is fragmented and technology uptake is slow, resulting in irreversible climate tipping points.

The worsening of climate change will mean some vessels and goods will become uninsurable, due to inevitable increases in natural disasters and tougher conditions at sea that increase the risks of things going overboard.

The IPCC warns that technology development will play a crucial role in mitigating and adapting to climate change. However, this future assumes a gradual integration of technology.

Contrary to the first future, where the gradual uptake of technology is accompanied by co-ordinated efforts to limit warming to 1.5 degrees, the gradual integration of technology in this context means that sufficient emissions reduction is not achieved, exacerbating the existing challenges of adapting to an increasingly uninhabitable world.