Shipboard tasks such as working at heights and/or over the side, mooring and rigging (e.g. an accommodation ladder or pilot ladder) are considered high-risk operations. Unfortunately, these tasks are often conducted in an unsafe manner, AMSA highlights in its new Safety Awareness Bulletin with two case studies.

Case study 1

A seafarer fell in the cargo hold while undertaking repairs from the number 3 cargo hold access ladder and sustained fatal injuries.1 The Australian Maritime Safety Authority (AMSA) conducted a port State control inspection and investigation following this incident. The vessel was detained with significant deficiencies related to the vessel’s safety management system.

The investigation findings identified systemic failure in the vessel’s safety management system to ensure safe shipboard operations and maintenance of the vessel. The safety equipment, such as helmet and safety harness were in very poor condition and defective. The operator did not adequately maintain the safety equipment and did not provide safety harnesses required for working at heights. There was a lack of safety culture and leadership onboard the vessel.

Shortcomings included:

- poor risk assessment process

- failure to provide seafarers with safety harnesses and associated equipment for working at heights

- failure to maintain safety equipment and PPE

- failure to allocate available resources

- fatigue not appropriately managed.

Case study 2

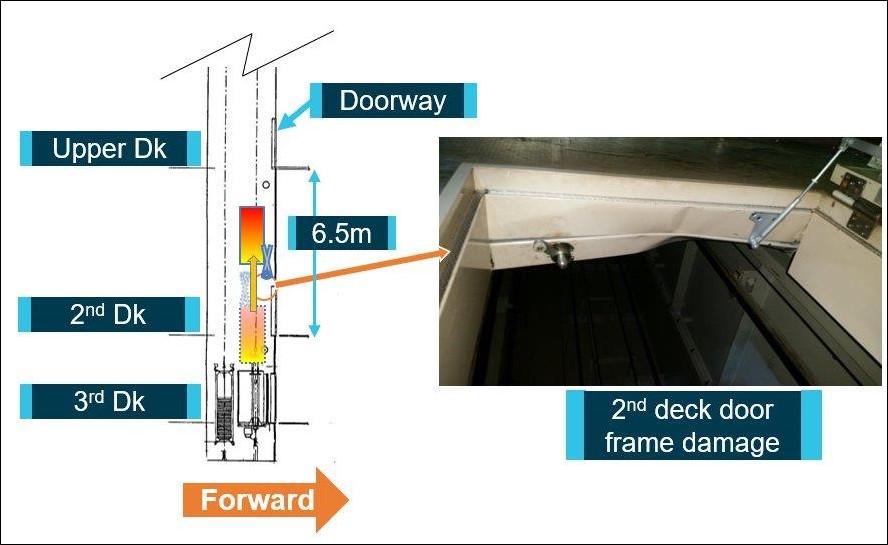

A seafarer was testing the ship’s personnel elevator after completing mechanical repairs.2 While on the elevator cage top, the seafarer was fatally injured after being trapped between the moving cage and the bulkhead.

The reasons the seafarer was in this position and became trapped could not be determined. However, seafarers onboard were not informed elevator work was being conducted and warning signs were not in place to indicate the elevator was out of service. This allowed elevator call requests to be made while the work was underway, while the seafarer was on the cage top.

For any task that is performed on multiple occasions without any adverse consequences, there is the potential for an individual’s perception of risk to decrease. Hence it is important to follow documented procedures and safe working practices, even when one considers the task/operation to be safe.

It is important that close and careful supervision is maintained for elevator testing and tasks. Supervisory oversight provides an external check and safety barrier before, and during, the work.

Marine incident data

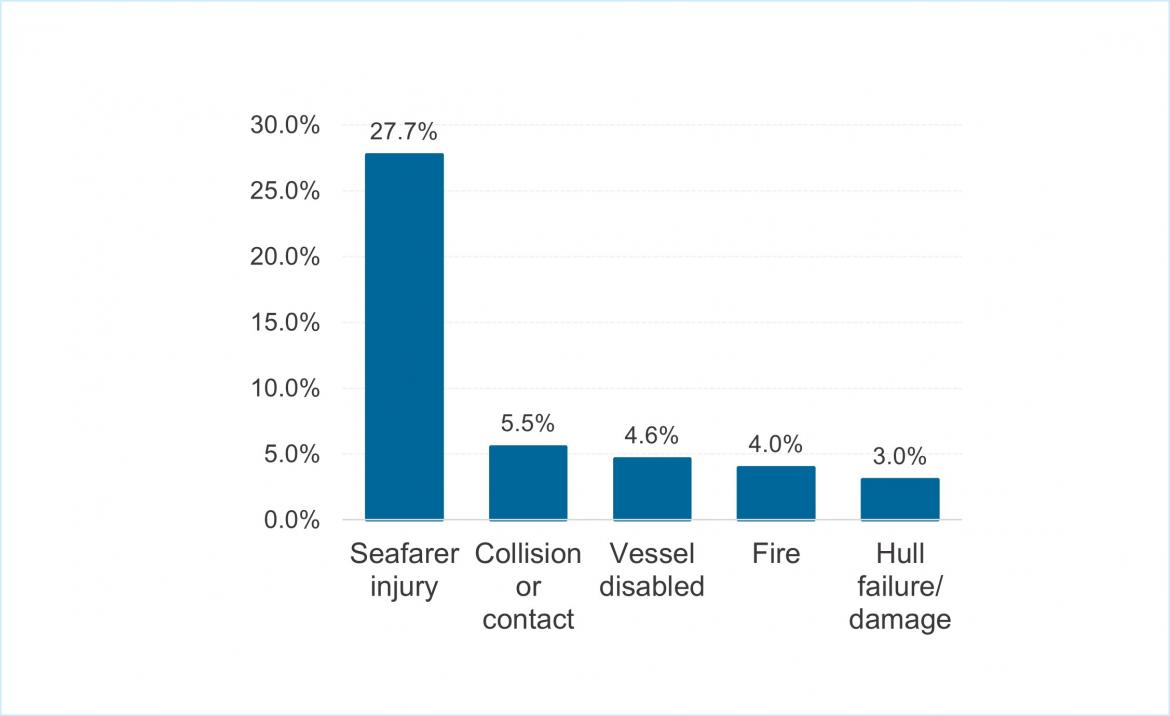

A total of 758 serious incidents were reported to AMSA between 2020 and 2022 on foreign-flagged and regulated Australian vessels. The top 5 reported serious incidents included:

- seafarer injury (27.7%)

- collision or contact (5.5%)

- vessel disabled (4.6%)

- fire (4%)

- hull failure/damage (3%).

Seafarer injuries make up most of the reported serious incidents, which suggests safe working conditions and associated practices is an ongoing issue on board vessels visiting Australia.

Port State control (PSC) deficiencies

This issue is further evidenced in the PSC data. There is an increase in the number of Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 (MLC) PSC deficiencies recorded against Regulation 4.3 – Health and safety protection and accident prevention.

How acceptable is unacceptable?

Over time, seafarers may develop informal practices and shortcuts to circumvent deficiencies in equipment design, poor procedures or policies that are incompatible with the realities of daily operations. If seafarers are continuously exposed to these practices, they are more likely to perceive the risks as low. This leads to a situation where poor practices and risky activities repeated over time are perceived as being normal.

Additionally, if supervisors and operators allow risk-taking behaviour to continue unchecked and have not effectively addressed these poor practices or shortcuts, these practices will often be deemed as acceptable behaviour by seafarers. This can create unsafe and poor working conditions onboard.

Importance of safety culture

Safety culture broadly refers to the shared perceptions of safety policies, procedures, behaviours and practices of seafarers and the companies in which they work. It is now well known that safety culture is a significant determinant of safety outcomes and is a leading indicator of accidents and injuries. It is important to note that having a safety procedure does not create a safety culture.

Seafarers carry out tasks in a cross-cultural working environment. To establish a positive safety culture, operators need to recognise cultural biases that may arise due to the different cultures of the seafarers and shore-based staff as doing so will ensure they can effectively address these differences or barriers.

Safety culture cannot be established without clear leadership and a prioritisation of safety. Effective leaders communicate clearly on safety standards and hazard identification and motivate the shipboard team to make safety a priority.

Communication and consultation

When a risk has been identified, it needs to be controlled. Both the identification and implementation of risk controls are likely to be more effective when different perceptions are recognised and taken into consideration. It is important that the seafarers on board are consulted and that their views together with other knowledge of risk are taken into account in the risk management process.

People’s individual perceptions may influence:

- willingness to consider new information

- confidence or trust in such information

- the relative importance given to information.

Effective communication and consultation will ensure everyone involved understands the basis on which decisions are made and the reasons why particular actions are requested.

Commitment to safety

The success of a safety culture depends on cooperation and commitment from all involved and this commitment to safety must come from the top.

Leaders can start by ensuring tasks are adequately supervised, training is provided, workload and fatigue are managed effectively, and policies clearly prioritise safety above time pressures. Seafarers can contribute by following procedures, always using safety equipment, reporting defects, not taking undue risks because it takes less effort and remembering that even work that is done frequently can be dangerous.

This in effect leads to all parties being committed, not just because of rules and regulations but through individual choice, to safe actions and behaviours at all times, both during work and recreational activities on board.

Key messages

- Poor practices and shortcuts repeated over time gradually become the norm.

- An effective safety culture promotes the understanding to all seafarers that the goals of the company will be achieved through accepted safety procedures, practices and behaviours.

- The identification of risks and the implementation of risk controls are most likely to be successful when people’s perceptions are recognised and taken into consideration.

- Effective communication and consultation with everyone involved in task and work can improve the risk management process.