The UK MAIB Safety Digest in one of its cases highlights lessons learned concerning a passenger cargo ship grounding incident due to unexpected heavy weather.

The incident

Early in the morning, having disembarked passengers and completed cargo discharge, the master of a passenger/ro-ro cargo ship decided to anchor in the approaches to a port for a scheduled layover period. The wind was southwest at 30 knots, and was forecast to increase throughout the day and to peak in excess of 40 knots during the evening.

The ship was anchored with 8 shackles of cable close to the main channel and south-west of its normal position to gain better holding ground and to maximise its distance from a small island astern. The master ordered the four main engines to remain on 5 minutes’ notice. One main engine, driving a shaft alternator, was left running and available to be clutched in immediately should it be required.

The master then handed over to the OOW, and left written instructions for him to instruct the engineer on watch to clutch in the main engine and to call both the master and the bosun should the OOW suspect that the anchor was dragging.

The master intermittently returned to the bridge throughout the day to monitor the wind speed and weather forecast. By early evening, the wind had increased to 50 knots, causing the ship to yaw up to 60° either side of the wind direction. The chief officer, who happened to be on the bridge with the OOW, heard noises emanating from the forecastle and decided to investigate with a duty seaman.

The master then returned to the bridge and, noting that the wind speed was now about 65 knots, looked at the electronic chart display and saw the ship’s history trail start to move astern. He immediately instructed the OOW to call the engine room to start a second engine and to clutch in the first. The engineer on watch acknowledged the instruction. He then slowed down the running engine in preparation to engage the clutch, and then began to start the other three main engines.

Meanwhile, the ship continued to drag its anchor and to drift north-eastwards at about 3 knots. It grounded a few minutes later, shortly before the engineer on watch handed control of all four main engines to the bridge.

Lessons Learned

1. In deciding to anchor in the port approaches, the master considered there would be little protection from the wind and sea immediately outside the port and that the number of small islands within the port approaches would provide an adequate lee for the ship. He dismissed the option of proceeding to sea and then heaving to in more sheltered areas along the coast. However, such an option was feasible considering the length of the scheduled layover period. The master’s decision was influenced by his previous successful, albeit limited, experience of anchoring similar ships in wind speeds of up to 40 knots. The forecast wind speed was at the assumed maximum design limit of the anchoring equipment. However, the ship’s tendency to yaw in such conditions, which the master was not familiar with, would have increased the loading to beyond that limit. Are you familiar with your ship’s anchoring capabilities and performance? Without first-hand experience to draw on, such information can be lost unless specifically covered during handover periods and, in particular, when a ship is sold on, or there is a change of manager.

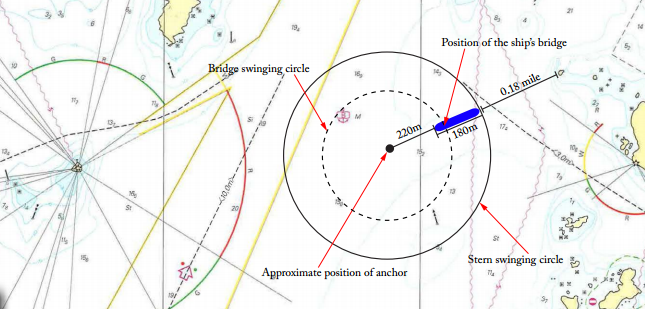

2. Having decided to anchor the ship in the port approaches, the master then needed to appraise his intended anchorage, fully assess the consequent risks, plan the anchoring operation and implement appropriate safeguards to prevent the ship dragging anchor and/or running aground. In view of the forecast wind speed and direction, the master wisely modified the ship’s normal anchoring position and increased the amount of cable from that normally used. However, he did not construct a swinging circle either at the planning stage or after anchoring. Had he done so, he might have more acutely recognised the limited time that he would have available in which to arrest the ship’s drift should the anchor start to drag, and might have been encouraged to reconsider his decision to anchor. Do you construct an anchorage swinging circle as a matter of routine?

3. As the wind speed increased throughout the day, the anchor remained in position, which reaffirmed to the master that the amount of deployed cable was probably sufficient to prevent the anchor dragging in the forecast conditions. He also remained confident that, by clutching in the running engine, the ship’s drift could be satisfactorily arrested to prevent it from grounding should the anchor begin to drag. However, particularly once the wind speed had exceeded what had been forecast, the master could have taken more proactive measures, such as clutching in the running engine, starting the other main engines, and manoeuvring the ship ahead to reduce loading on the anchoring equipment. He could also have lowered a second anchor to the seabed to reduce the ship’s yawing. The master lacked an appreciation of the ship’s likely rate of drift should it start to drag anchor in the prevailing wind conditions. His expectation for the running engine to be clutched in immediately if the ship dragged its anchor was not effectively communicated to the engineer on watch. However, even if it had been clutched in immediately, it is uncertain that its sole use would have prevented the ship from grounding.

4. The master did not consider the possibility of the ship experiencing stronger winds than those forecast. With no contingency plan developed to address this eventuality, the trigger point at which a response was executed became the point at which the ship started to drag its anchor. Hoping for the best should never be an option.

Source & Image credit: UK MAIB