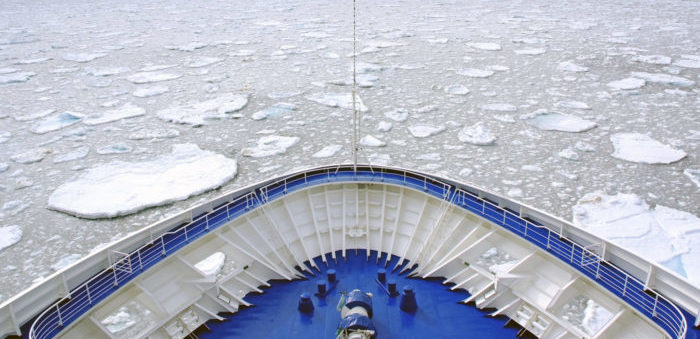

A newly published study revealed that the movement of sea ice between Arctic countries is expected to rise this century, also increasing the risk of more widely transporting pollutants like microplastics and oil.

Specifically, the study that was published in the journal Earth’s Future forecasts that by the middle of the century, the average time it takes for sea ice to travel from one region to another will decrease by more than half, and the amount of sea ice exchanged between Arctic countries such as Russia, Norway, Canada and the U.S. will more than triple.

Patricia DeRepentigny, a doctoral candidate at the University of Colorado, Boulder stated that

Ice moves faster, but as the climate warms, it doesn’t have as much time as before to travel before it melts. Because of that, we really see that it’s the regions that are directly downstream of each country’s waters that are going to be most affected.

It has been reported that contaminants in frozen ice are able to travel much farther than those in open water moved by ocean currents.

Following the melting of the ice, sea ice is thinning and melting entirely across vast regions in the summer, the more open water means the area of new ice formed during winter is actually increasing. This is the case particularly along the Russian coastline.

The study commented that the melting will most likely extend into the central Arctic Ocean; This means that thinner ice can move faster in the increasingly open waters of the Arctic, delivering the particles and pollutants it carries to waters of neighboring states.

Thus, experts believe that Russia’s exclusive economic zone and the central Arctic Ocean are two places that will form new ice, making them “great” exporters of ice to the other regions in the Arctic.

The researchers used a global climate model, together with the Sea Ice Tracking Utility, to track sea ice from where it would form to where it would ultimately melt during the 21st century.

They considered two different emissions scenarios:

- the more extreme “business as usual” scenario, which predicts warming of 4 to 5 degrees Celsius by 2100

- a warming scenario limited to 2 degrees Celsius, inspired by the Paris Agreement.

They then modeled how sea ice would behave in both these scenarios at the middle and the end of the century. In three of these four situations, including both mid-century predictions, the movement of sea ice between Arctic countries increased.

However, in the high emissions scenario at the end of the century, the researchers resulted that countries could end up dealing more with their own ice and its contaminants than ice from their neighbors. In that case, the majority of sea ice that freezes during winter would melt each spring in the same region where it formed.

Concluding, the study was coauthored by Alexandra Jahn of the University of Colorado Boulder, L. Bruno Tremblay of McGill University, Stephanie Pfirman of Arizona State University and Robert Newton of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory.