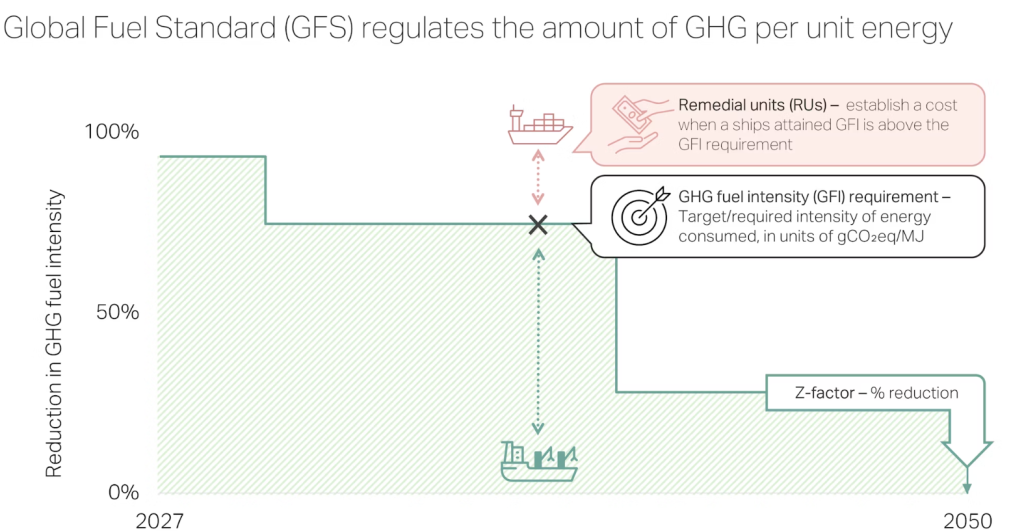

The Mærsk Mc-Kinney Møller Center for Zero Carbon Shipping (MMMCZCS) looks at the importance of the reduction values, Z-factors, in a Global Fuel Standard (GFS) in achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

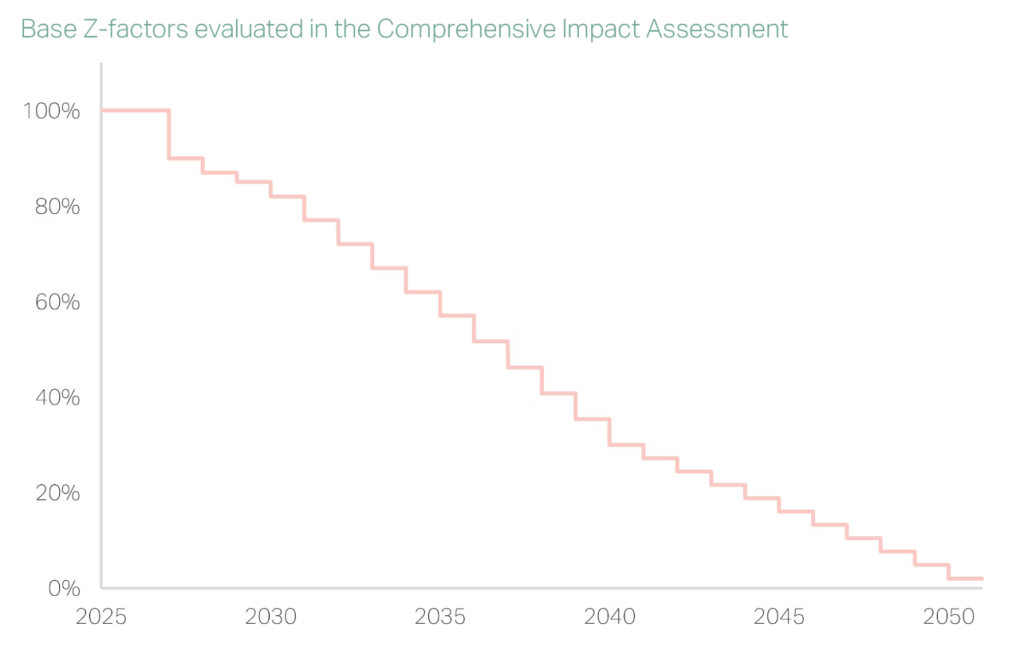

Known as the Z-factors or reduction factors, these values establish a limit on annual GHG intensity per vessel. MMMCZCS used an integrated assessment model, NavigaTE, to evaluate Z-factors from scenarios in the Comprehensive Impact Assessment report by DNV. The Center analyzed if these Z-factors enable a transition to net-zero in line with the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy.

Key points

- If the penalty set for non-compliance enables the uptake of sustainable fuels and energy, then Z-factors set the pace and scale of the transition.

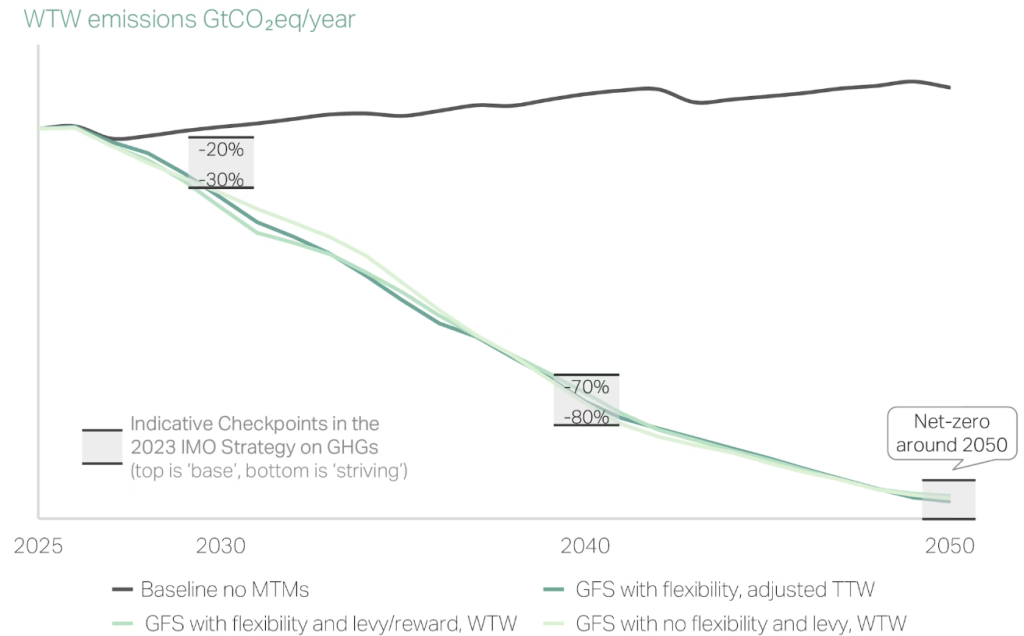

- Using MMMCZCS NavigaTE model, MMMCZCS validated the ability of ‘base’ Z-factors from the Comprehensive Impact Assessment to meet the 2023 IMO GHG Strategy’s indicative checkpoints.

- The Z-factors must strike a balance between ambition and feasibility. Setting an unachievable reduction trajectory could potentially lead to rollbacks that undermine confidence in the measures and work against decarbonization.

The MTMs come with an evolving list of terms and acronyms, which can be hard to navigate. Here are a few key definitions important for understanding this edition’s topic, based on the working report from the MEPC on MTMs (MEPC 82/WP.9):

- Global fuel standard (GFS): technical measure that regulates the phased reduction of GHG intensity of marine fuels

- GHG fuel intensity (GFI): the amount of GHG emissions per unit of energy used on board a ship, typically expressed in terms of grams of CO2-equivalent per unit of energy (e.g., gCO2eq/MJ)

- GFI requirement, also known as target/required annual GFI: the target/required value for the average GHG intensity of all fuels used by international shipping for a given calendar year (following the Comprehensive Impact Assessment, MMMCZCS uses ‘GFI requirement’)

- Z-factor, also known as reduction factor: represents the annual percentage reduction in the GFI, which determines the required trajectory of emissions intensity reductions

- Remedial unit (RU): establishes the cost when a vessel’s attained GFI is above the requirement during a reporting period

Aligning Z-factors with decarbonization goals

Z-factors and absolute emissions reductions aren’t the same

The GFS regulates a vessel’s emissions intensity rather than the sum of total annual emissions (absolute emissions). Therefore, finding the right Z-factors to meet the indicative checkpoints for absolute emissions in the Strategy depends on future growth of shipping.

Pathways in the Fourth IMO GHG Study assume growth in global maritime trade. Drawing on development pathways, that study anticipates a decrease in trade in some shipping sectors (e.g., dry bulkers carrying coal), but this decrease is more than offset by growth in other sectors (e.g., containers). As a result, GFI requirements, which are based on emissions intensity, need to go beyond targeted absolute emissions reductions to compensate for trade growth.

The base Z-factors are a good candidate to align with the Strategy

The Comprehensive Impact Assessment report by DNV looked at ‘base’ Z-factors that align with the less ambitious indicative checkpoints in the Strategy. This scenario is also the basis of proposed Z-factors in the latest MTMs proposal from the EU and Japan (IMO-GHG 17/2/2), while the two other proposals considered in MMMCZCS analysis (see below) do not specify Z-factors.

MMMCZCS evaluated three versions of the MTMs based on existing Member State proposals:

- GFS with flexibility, adjusted TTW (ISWG-GHG 17/2/7): This proposal consists of a GFS with the ability to trade surplus units with flexibility. The emissions scope is tank-to-wake (TTW) adjusted using well-to-wake (WTW) scaling factors.

- GFS with flexibility and levy/reward, WTW (ISWG-GHG 17/2/2): This proposal also has a GFS with flexibility, but adds a levy with a reward scheme and a WTW emissions scope. The levy is assumed to contribute 100 USD/tCO₂eq, with the reward applying only to e-fuels, starting at 400 USD/tCO₂eq abated and declining to 200 USD/tCO₂eq abated in 2040.

- GFS with no flexibility and a levy, WTW (ISWG-17/2/15): The final proposal evaluated has a GFS without the ability to trade surplus units. This proposal includes a levy and has a WTW emissions scope, with the levy assumed to contribute 150 USD/tCO₂eq.

Simulations show that all three proposals can meet the emissions reduction targets in the Strategy when using the base Z-factors and an RU of 450 USD/tCO₂eq. The results are very similar across the proposals, suggesting that the most important factors for driving sustainable fuel adoption are 1) the base Z-factors and 2) the RU of 450 USD/tCO₂eq. Without these two elements, the MTMs are unlikely to achieve the desired emissions reductions.

Other factors, beyond just the RU and Z-factors, can also affect the results. For example, allowing flexibility in the system could reduce the cost of transitioning by letting those with the lowest emissions reduction costs take on more of the required reductions. A levy with rewards or a feebate system could encourage the use of sustainable fuels. Additionally, generating revenue will be essential to fund initiatives that ensure a fair transition. All of these elements are crucial for the long-term success of the MTMs and achieving decarbonization in the maritime industry.

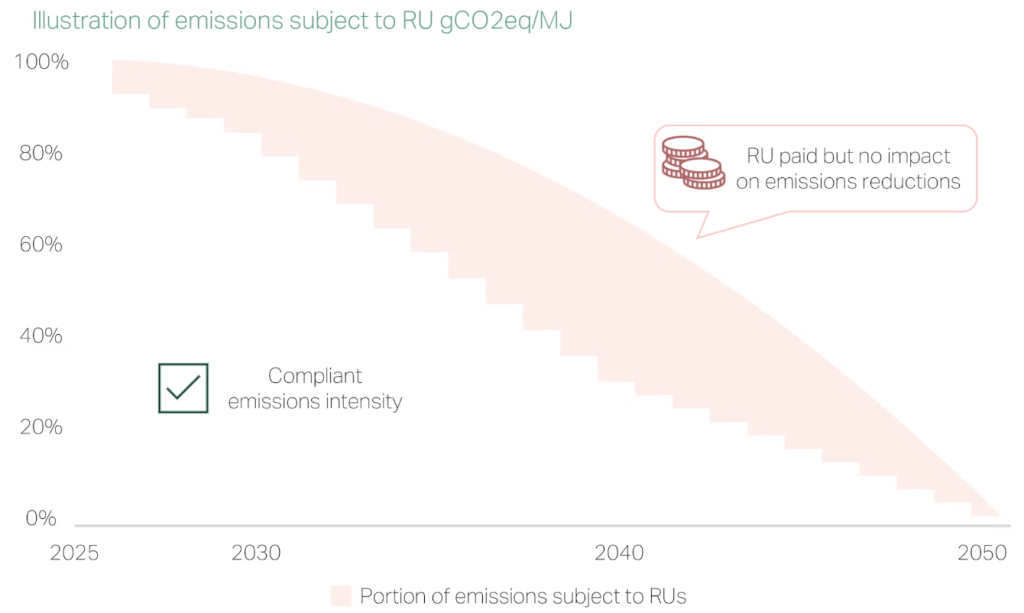

There is such a thing as overly ambitious Z-factors

Unlike a levy, the goal of a GFS is not to add costs for GHGs, but to ensure consistent emissions reductions by driving a transition to sustainable energy. However, if Z-factors are set too high, exceeding the global fleet’s ability to adopt sustainable alternatives, the GFS will drive substantial RU payments with minimal additional emissions reductions — a consequence that should be carefully considered when designing the MTMs.

Unrealistic targets that fail to drive a transition to sustainable energy, while simultaneously substantially increasing shipping costs, could lead to rollbacks of the regulations. This would undermine stakeholder confidence that the measures will remain in place, with negative consequences for decarbonization.

MMMCZCS has already seen some real-world examples of this risk of rollbacks becoming a reality. For instance, the US’ Renewable Fuel Standard set aggressive biofuel blending targets, but slow production of advanced biofuels forced lawmakers to adjust mandates in 2023. Similarly, the UK initially planned to ban the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030, but revised the cut-off to 2035 due to infrastructure and market challenges.

In the shipping context, setting Z-factors beyond what is practically feasible risks similar rollbacks. Overly ambitious targets are likely to face challenges including upskilling of workers, port infrastructure, competition with other sectors for scarce fuels and feedstocks, and limited shipyard capacity for newbuilds and retrofits.

Given these challenges, industry needs confidence to invest in new systems and technologies. A GFS trajectory that does not seem practically achievable can lower confidence and investment if companies expect changes. Investors may stay on the sidelines if they believe that overly ambitious targets are unachievable and therefore will inevitably be removed or reduced.

A recent report from the European Investment Bank found that uncertainty about whether ambitious government mandates would be maintained was a key investment risk for fuel suppliers. Furthermore, IMO policy that fails to achieve its goals could trigger political backlash or lack of faith in future measures. Therefore, Member States should agree on ambitious but feasible Z-factors.

By pairing ambitious but feasible Z-factors with strong incentives through a sufficiently high RU, a GFS can create the certainty needed for fuel producers and shipping operators to confidently make long-term investments in maritime decarbonization, MMMCZCS concludes.