As UK MAIB reports in its most recent Safety Digest, it was another busy day of operations for a workboat at an offshore wind farm. Sailing early, the workboat was due to transfer two teams to carry out maintenance tasks on two different wind turbines.

The incident

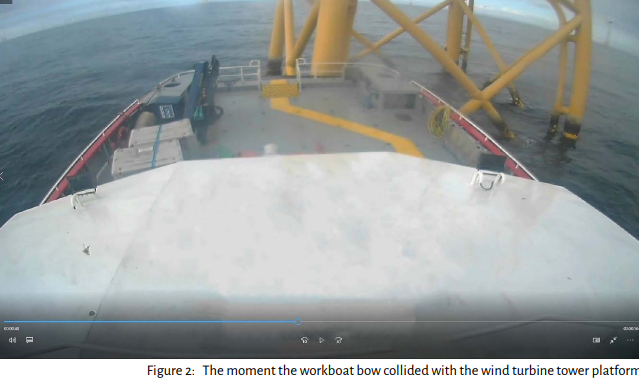

Equipped to push onto a wind turbine tower platform with its protected bow section, this catamaran workboat was well designed and allowed easy transfer of the maintenance crew to and from the wind turbine towers. The workboat’s crew of master, mate and crewman were relatively new to the wind farm and still adjusting to local practices and their new contract. Having delivered the two work teams, the master found themself with some time to spare before the next scheduled job and decided to crack on with some paperwork.

The company’s standing orders did not permit workboats to secure to wind turbine platforms during standby, nor to use autopilot while navigating through wind farms. Hoping that they would have time to complete the administration task, the master decided to set minimum power ahead and steam on a course between the wind turbines. Meanwhile, the mate was on the aft deck completing some familiarisation training and the crewman busied themself organising

the on board stores. The master was working at the aft-facing chart table on the bridge, but had become engrossed in paperwork and lost track of time. The workboat was travelling at 5kts and, without the autopilot switched on, started turning slowly to starboard.

The master was shocked to see one of the wind turbine towers looming ahead when they looked up and turned to face forward. The collision happened before there was chance to react. The workboat took the brunt of the impact on its off-centre protected bow section and unsecured items were thrown forward across the deck as the vessel came to a jolting standstill. The crewman was thrown against a shelf and sustained two broken ribs. The master assessed the crewman’s injury and the damage to the workboat and returned to harbour to evacuate the crewman for treatment at the local hospital. Fortunately, there was little damage to the workboat other than small dents and abrasions. The master was left with a much larger paperwork mountain to climb.

Lessons learned

- Procedure → It is important to keep administrative tasks up-to-date, but crew and vessel safety remains the priority. Where paperwork must be completed, for example updating the bridge logbook while on watch, ask someone else to keep watch or post a lookout to maintain proper and effective visual navigation.

- Monitor → The slow turn to starboard may not have been evident from the bridge windows alone and watchkeepers should monitor all available sensors and equipment to establish an accurate navigational overview. Regular checks of data from an Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS), rate of turn indicator, and directional gyro, etc. allows the watchkeeper to identify hazards and take preventative action to avoid an accident.

- Communcate → Raise concerns if paperwork becomes unmanageable or imposed procedures interfere with best practice. Communication is a two-way process and constructive feedback about what works well and what could be improved helps people and organisations understand the impact of their decisions. It is important that vessel reports are submitted in a timely fashion; talking about the challenges faced at sea reduces the opportunity for conflict between compliance and safety.