Working on ships isn’t one of the easiest jobs in the world. It is a challenging profession that needs energy at all times. That is why fatigue is seen as a significant contributory factor to many incidents in shipping industry and one of the major concerns for seafarers.

The aim of the rest hour requirements is to avoid or minimize fatigue. The issues of adequate crewing and the effect of fatigue upon health and safety are clearly closely related. It is also notable that the cumulative effect of fatigue-inducing factors has an exponentially negative impact on the seafarers concerned.

Additionally, watchkeeper incapacitation is a serious issue, which leads to a number of groundings each year. For instance, a typical example of watchkeeper fatigue occurred at 05:15 on a June morning when a 1,990gt general cargo vessel ran aground on the west coast of Scotland. The chief officer had been on watch since midnight and was suffering the cumulative effects of fatigue generated by the 6 on 6 off watchkeeping routine punctuated by regular port visits where he was expected to oversee all cargo operations. The chief officer fell asleep standing at the controls between 04:05 and 04:15 and missed a planned alteration of course. He woke an hour later, still standing, as the vessel grounded.

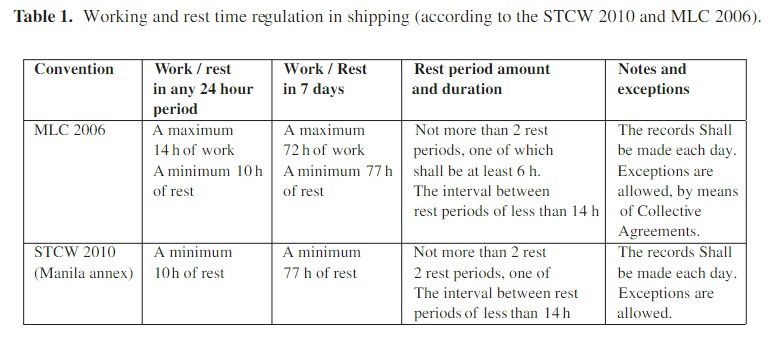

The legal limit on how many hours to work on ships is addressed by ILO, taking into consideration the needs of marine industry. The hours of rest on vessels are defined as ‘non-working hours’; these do not include the intermittent breaks. The regulation concerning the working and rest time periods in shipping, according to the STCW 2010 and MLC 2006, is shown in Table below.

The hours of rest can be divided in a maximum of two periods, one of which should be at least six hours in length. Two such consecutive periods should not be separated by more than 14 hours. A seafarer must be granted a compensatory rest period in case he/she is required to be on call during rest hours. Moreover, operations like lifeboat drills, firefighting drills, and drills prescribed by national laws and regulations should be conducted so as to ensure minimum disruption of rest period.

Number of ship working hours and hours of rest for crew members in all positions must be displayed in a place of easy accessibility for purpose of informing the seafarers in due time. A log recording number of hours of work and rest for every crew member must be always maintained.

However, an exception can be made to all the above-mentioned, in case the master of the ship deems it necessary to require services of a seafarer in lieu of maintaining safety of ship, especially on emergency basis. Master can suspend the schedule of work hours and hours of rest in situations of vessels distress and require a seafarer to perform necessary duties until normal conditions are restored.

In addition, deck and engineer officers, along with apprentices and cadets may be required to work more than the above-mentioned limits, all of which shall be considered overtime. For each hour of overtime work, the officer would be entitled to compensatory hours of rest and overtime remuneration.

Problems in calculations

Rest hours as defined in STCW are the same with those of MLC, although many industry insiders are confused with the work period issue that according to a 77 hours rest week leaving 91 hours work week (7×24 – 77 = 91).

Another problem is that Master’s Overriding Authority, included in identical statements in MLC and STCW, needs implementation guidance (e.g. when this may be implemented, record keeping, implications etc.) and STCW Exceptions are not properly defined for implementation (STCW A-VIII/1, para 9, 77 to 70 hours and Max 2 rest periods to 3 rest periods namely).

The consequences of non-compliance with MLC, 2006 are evident from the number of inspections and detentions recorded authorized by port state controls (PSC) regarding deficiencies related to MLC, 2006.

The most common grounds for detention are:

- Records of rest (STCW)

- Seafarers’ Employment Agreement (SEA)

- Fitness for duty – work and rest hours

- Manning specified by the minimum safe manning document (STCW)

- Ensure proper working and living conditions onboard with adequate manning of the vessels to ensure workloads are properly met

- Set, define and strictly register officially rest or work hours only (rest hours are suggested)

- Ensure proper guidance is provided with respect to record keeping and that all crew is not working more than 91 hours in any given 7-day to make it more simple

- Ensure Seafarer Employment Agreements (SEAs) do not violate the max of 91 hours per week work and that the total work and overtime provided by the crew is in line with that

- Employ software to monitor rest hours, ask copies of completed records for review at the office and provide tips and feedback to the vessels

- Provide guidance for the implementation of Master’s Overriding Authority (relevant entry should be made in the ship’s log book, conditions to be defined etc.). In any such case, office should be notified and provide feedback to vessels

- Regarding STCW exceptions, check if vessel’s flag allows for the 77 hours work to shift to 70 hours and provide exact guidance and examples for recordkeeping

- Suggest Masters to make an entry into log book for the split of rest periods to 3 MAX per 24 hours a minimum of 24 hours in advance of a scheduled drill period. This will minimize the technical deficiencies observed in the rest hours record keeping at the date of the drill

Concluding, accident statistics show a strong association with factors that increase the risk of fatigue, such as under manning and long working hours. Seafarers fatigue is an occupational health and safety issue that is common and widespread. Latest MARTHA Fatigue Report revealed that fatigue has safety and long-term physical and mental health implications and long tours of duty (over 6 months) may lead to increased sleepiness, loss of sleep quality, reduced motivation which could contribute to ‘near-misses’ and accidents onboard. According to the report, night watch keepers are most at risk from falling asleep on duty, while captains feel stressed and fatigued at the end of their tours of duty and need recovery time. Simple operational solutions can ensure sleep is easier for those onboard through an effective fatigue risk management.

What is the norm for a non compliance of rest hours, whereas not being compensated thereafter by an operator?