Years ago, above the entrance to the navigation bridge was a brass plaque which stated “for use in navigating the ship”. This use has become corrupted over the years and many non navigational tasks were undertaken such as preparing safety equipment stencils, preparation of crew lists and cargo plans; all were a distraction to navigation safety. Captain Mark Bull FNI, Principal, Trafalgar Navigation Limited explains how this situation arose.

If those charged with the design of ships’ navigational bridges became design engineers in the automobile industry tomorrow we would probably see a car with the pedals (accelerator, brake and – where fitted – clutch) in the rear near side, the steering wheel in the rear off side, instruments in front near side (where the passenger sits) and light switches/direction indicators under the central arm rest.

Yes take it from me, navigation bridge design is that bad!

Originally the navigation bridge had 3 key spaces; a chart room, a radio room and a wheelhouse. By the late 60s and early 70s, the chart room disappeared and the function it provided was moved into the wheelhouse by providing a large chart table separated from the wheelhouse by a curtain only. The introduction of GMDSS saw the disappearance of the radio room and a small radio console was provided alongside the chart table, separated by a small space creating the passage to the wheelhouse. In daytime, curtains were drawn back allowing the OOW to be able to view the whole navigation bridge from behind the chart table and, depending on design, a view out of the bridge windows. We now see even the chart space disappear and have a single space, totally enclosed stretching from one side of the ship to the other; 60 metres wide in some cases.

The provision of large tables made the chart room/space an ideal location for carrying out many administrative related tasks and with the appearance of computers this increased. The temptation to perform such tasks on watch was amplified. Today, it becomes clearer that the navigation bridge is not the place for administration to be carried out as it is a serious distraction to safe navigation.

Again over the corresponding period of time, instrumentation has changed; hyperbolic navigation system receivers came and went, transit satellite navigation came and went, radio direction finders disappeared, GNSS arrived followed by DGPS and even the latter is soon to go. Paper recording systems are now replaced by electronic systems, records being downloadable to USB drives. Of course the final piece in the instrumentation jig-saw has been the arrival of ECDIS, the real game changer.

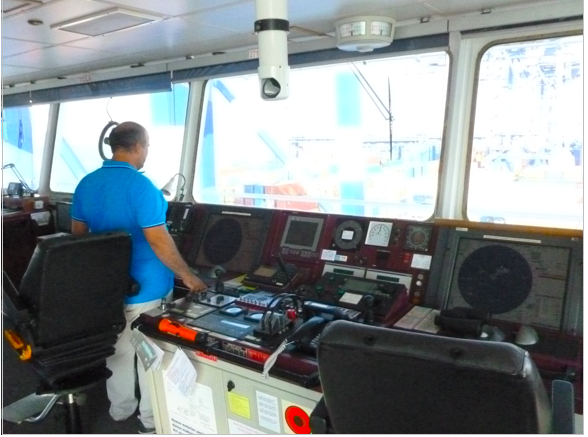

Originally all these instruments and navigational equipment were grouped around the chart table to enable the OOW to plot the ship’s position and monitor the progress. Not much thought was given to the location of this equipment.

As they moved from bridge wing compass repeater to radar to chart table, especially at night, to plot the ship’s position, situation awareness was temporarily lost. Vision was impaired moving from dark to light to dark again.

This instrumentation has moved now to the navigation bridge console, and in some limited cases, it takes on the appearance of an aircraft cockpit. Core instrumentation (ARPA, ECDIS, GPS) are duplicated in a mirror image to permit the pilot – co-pilot configuration and more importantly the person having the CON has all the information at their fingertips. In many other cases however, the concept on an engine control room has been allowed to dominate and the console has extended ever further toward the bridge wings.

Any advantage of having a single space and removing the need to go backwards and forwards to review the position has been negated by now having to move large distances from side to side, taking the OOW away from the critical alarms and alerts provided by new instrumentation. The instruments appear to have been located in the available space without much thought been given of how they are to be used (old problems just moved forward)

SOLAS neatly describes the angle of vision from the conning position in Regulation 22 of Chapter V, however nowhere does it state where the conning position is. There should be a clear statement somewhere on a ship’s safety equipment certificate exactly where this is. If it is by the ECDIS/ARPA as described in the previous paragraph, then I would argue that due to total internal reflection on these wide beamed vessels, the ship would not comply with the angle of visibility. It is 2021! How do they manage a visual lookout on a submarine? Would it be so difficult to provide a periscope style system to provide enhanced visual surveillance?

Also consider the size of the central console where the main engine telegraph is located – it tends to be huge. The designers need to take a look at how Jaguar, Boeing or Airbus deal with this. What about the cluster of instruments on the deckhead? They look as though they came from a 2nd World war submarine and why are they on the deck head anyway – you know the answer; because that is where we have always located them. The time has arrived to use some of the nice clear digital displays that are available and locate them where they are needed – directly in front of the pilot/co-pilot and just above the ARPA/ECDIS.

The clear and present danger of today is the “all-in-one” display thrust upon navigation officers by instrument designers who insist on wanting to put everything on a single screen. Such a culture may work in an office based scenario where small fonts are acceptable, but not on the bridge of a merchant ship

If we reduce the console to the horseshoe arrangement, it would be possible to reduce the physical side of the navigation bridge to a little more than the size of the horseshoe itself. How many times and for what duration do OOWs, Masters and Pilots need to go out to the bridge wing anyway? Which cars do not have reversing cameras today? So why can we not have docking cameras on bridges overlaid with Doppler log information (fore and aft & athwartships speeds)?

It is time for the design of ships’ navigational bridges to take into consideration what today’s navigation entails. When that simple task is done, then the physical size of the wheelhouse may be reduced. This in turn will improve visual watchkeeping and aid to integrate information from instrumentation. Most importantly it will reduce the stress during busy periods of navigation and in turn improve safety.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of SAFETY4SEA and are for information sharing and discussion purposes only.