The US President’s decision to slap a 25% tariff on steel imports raise concern, triggering urgent calls for diplomatic efforts to prevent an escalation which could have a significant impact in the maritime sector. However, this might not be all bad news, as alternative trading patterns could lead to an increase in tonne-mile demand, noted Drewry shipping consultancy.

As explained by Rahul Sharan, Lead Research Analyst, Dry Bulk, the Trump Administration had three options in order to support the country’s steel industry:

- A tariff of at least 25% on all steel imports from all countries

- A tariff of at least 53% on all steel imports from 12 countries (Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Egypt, India, Malaysia, South Korea, Russia, South Africa, Thailand, Turkey and Vietnam) with a quota by product on steel imports from all other countries equal to 100% of their 2017 exports to the US

- A quota on all steel products from all countries equal to 63% of each country’s 2017 exports to the US

In the end, Trump plumped for Option 1, possibly because its simplicity made it the most Twitter-friendly. The hostile reaction from its trading partners was entirely predictable, with little credence given to the stated reason of needing domestic steel supply for its tanks and warships. Such reactions have seldom deterred the present administration, but the horse trading has begun in earnest.

[smlsubform prepend=”GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!” showname=false emailtxt=”” emailholder=”Enter your email address” showsubmit=true submittxt=”Submit” jsthanks=false thankyou=”Thank you for subscribing to our mailing list”]

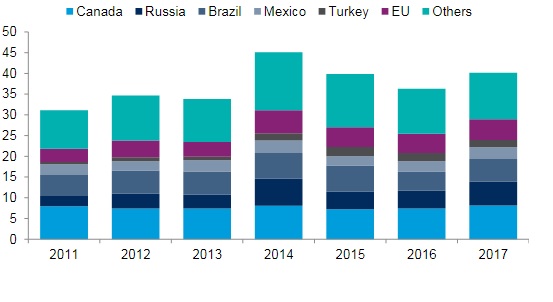

Canada is the largest steel exporter to the US, followed by Russia, Brazil, the EU and Mexico. Canada and Mexico have already secured exemptions on tariffs, but with a warning that their exemptions could be withdrawn if they tranship foreign steel into the US while passing it off as their own. The EU, Australia, Argentina, Brazil and South Korea have won an exemption, but only till May, leaving Russia, Brazil and Turkey to deal with the tariff issue. Most of them have already threatened to retaliate.

China – whose cheap exports have destabilised steel industries across the globe – can expect few concessions, so its response will be based on retaliation. Beijing is already threatening action against US technology companies operating in China, hoping that they will put pressure on Washington. Cars, agricultural products and ethanol are on Beijing’s hit-list.

What does Trump want?

Drewry research notes that:

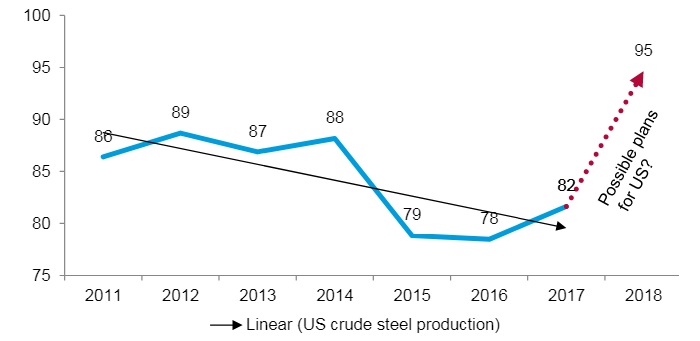

- The clear motive of the US government is to arrest the slide in domestic steel production. Before the financial crisis of 2009, the US was producing close to 100 million tonnes of crude steel every year. Since then, it has been sliding year after year, and slipped below 80 million tonnes in 2015, before registering a marginal increase in 2017.

- Ironically, China’s year-on-year growth in steel production lagged the world average for nine of the 15 months to February, and February was its second weakest month since November 2016.

Washington hopes that the new tariffs will bring down steel imports by some 13 million tonnes so that their domestic mills produce more. The remedy is intended to increase the present operating rate of 73% of its capacity to approximately 80%, which is the minimum utilisation needed for the long-term viability of the industry, according to the Department of Commerce. This might be optimistic, considering that world average utilisation has not been above 75% since September 2014.

Positive and negative effects for shipping Overhauling trade routes to and from US will have ripple effects on dry bulk shipping, according to Drewry.