In this article, Captain Badri Tetemadze shares key findings of his scientific research on seafarers’ wellbeing which was conducted at the World Maritime University along with the professors: Maria Carrera Arce, Raphael Baumler & Inga Bartusevičiene as the supervisors.

The study revealed key factors from both seafarers and maritime stakeholders that answer the question “why does seafaring as a key occupation still suffers from the deteriorated conditions of wellbeing?”. As the study indicates, most of the factors are still very much present adversely affecting seafarers mental, physical and social wellbeing.

Lack of understanding and insufficient awareness

Study reveals that wellbeing is not embraced in the industry with all of its dimensions physical, mental and social1. For example, the certificate of seafarers’ medical fitness2 is mainly issued through examination at a physical dimension only, which serves as the evidence attesting to their optimal wellbeing throughout their work contract period. However, the only viable way to maintain seafarers’ wellbeing at an optimal level, particularly within the unique psychosocial workplace of the ship, is by not paying attention solely to the physical but also the mental and social dimensions of health. Disregard of any of the three dimensions will lead to failure to maintain the quality of wellbeing.

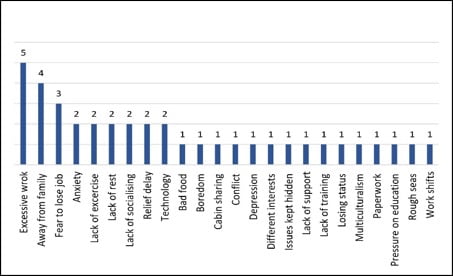

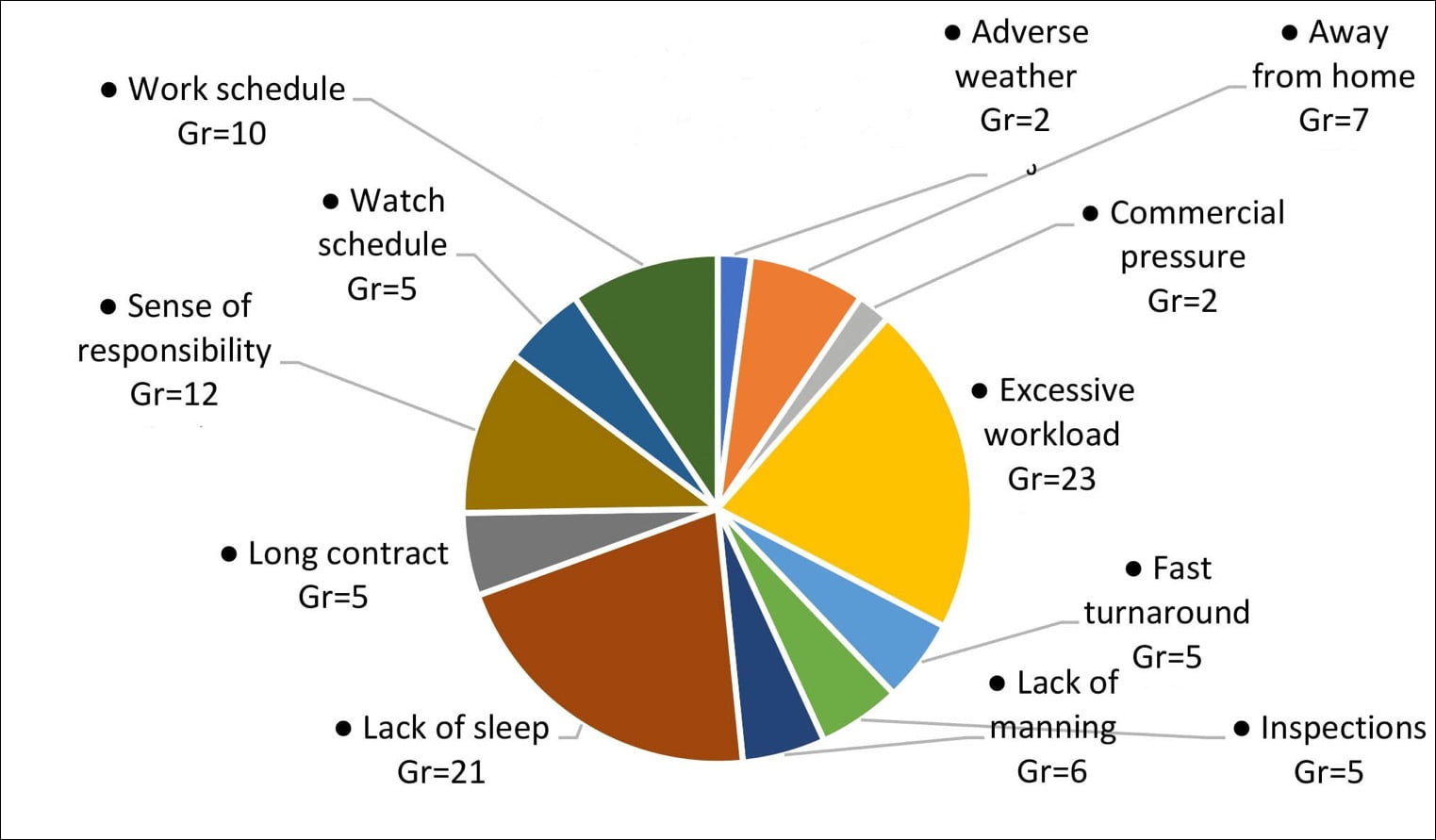

Furthermore, the study shows that level of awareness of those affected most (seafarers) doesn’t correspond to the same level as those who can set parameters for its improvement – maritime stakeholders. The latter are more aware of what exactly contributes to deterioration of seafarers’ wellbeing naming 24 various more detailed factors (Fig.1), while majority of the seafarers tend to mention mostly excessive workload and lack of sleep leading to severe fatigue (Fig.2).

Ineffective regulatory mechanisms and insufficient support onboard

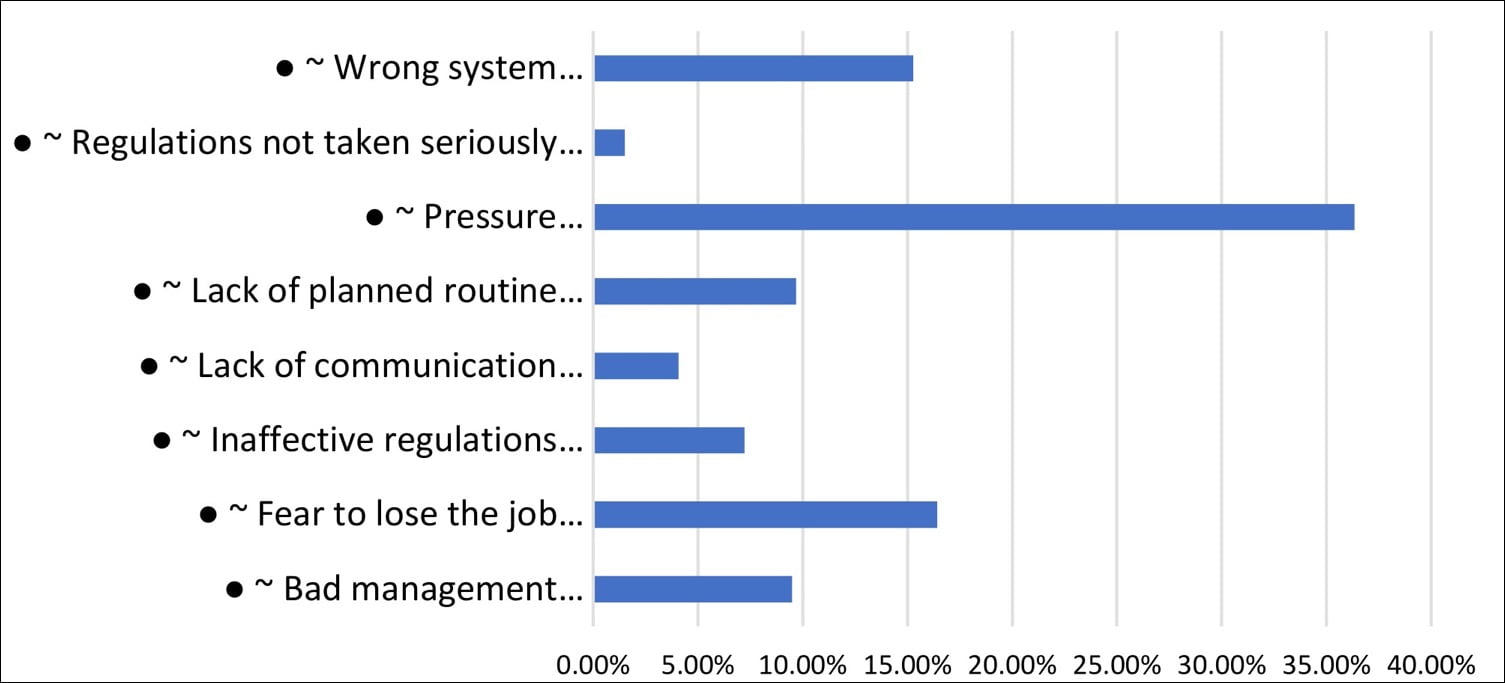

The study further reveals that although MLC 20063 does set out basic rights of those working at sea yet it fails to fully capture all dimensions of wellbeing in its regulatory mechanisms. It fails to deliver more explicit tools to maintain seafarers’ mental, physical and social wellbeing. In depth exploration indicates4 (Fig.3) most of the seafarers have to adjust their reports of the work and rest hours because of the pressure from the inferiors and a fear to lose the job to get the ship through the mandatory inspections and keep the employers satisfied.

This leads further to question the effectiveness of the MLC 2006 regulations as seafarers do still suffer from increased fatigue and lack of sleep. Even more, safety management system5 is found to be focused more on maritime incident and accident reduction principles rather also comprising onboard mandatory training tools for wellbeing monitoring and management and raising of its awareness.

Flag of convenience and their causes

As the study reveals, a majority of the seafarers find themselves unhappy at sea most importantly because of excessive workload, lack of sleep and lack of shore leave during long contractual terms. Analyzing the data, reduced manning emerged as the main cause to these factors further leading to severe fatigue, stress and anxiety. Seafarers mention lack of sleep as the second most causative factor deteriorating their wellbeing, followed by sense of responsibility (sometimes influenced by pressure from the company), work schedule and being away from family.

Analyzing the reasons leading to such excessive workload and lack of sleep, declined level of manning turns out to be as the most prevailing core issue among seafarers on all types of ships. Stakeholders tend to give more explanatory background to this fact rather than directly addressing why reduced manning levels exist onboard the ships. For example, international trade association firstly refers to the flag states’ obligations in setting proper minimum manning levels for the ships operating under their jurisdiction, and then to the ship masters to raise the question to the shipowners.

This finding can be supported by the trade union’s important arguments related to flags of convenience (FOC)6. It addresses the FOC as the inception of the issue. Ship owners use this opportunity for their favor in terms of preserving minimal regulations, focusing on more business with as few financial expenses as possible and, most importantly, obtaining freedom to employ cheap labour. This leads to the possibility of reducing the level of manning onboard ships leading to excessive workload and insufficient sleep.

This gives a tangible ground to the belief that shipowners have obtained some kind of freedom in handling crew members with the so called ‘hire and fire’ regime, which would reduce their operational costs.

The study has also revealed that spending most of the time onboard causes seafarers’ mental, physical and social distress and, as the results indicate, the ship’s fast turnaround, long voyages and now global pandemic restrictions have not always been the main reasons for lack of shore leave. Being fatigued and with lack of sleep, seafarers tend to stay onboard during off duty hours to have some sleep and rest to get ready for their work-related duties and obligations.

Conclusion

Shipowners’ freedom about handling crew with a ‘hire and fire’ regime gives seafarers’ few options to stand against sub-standards. With the fear of losing their jobs, a majority of them have to agree to sign long employment contracts and work in the most unpredictable and severe environments. They still experience tremendous pressure from workload and lack of sufficient rest with limited social life. Perhaps it is high time to assess such a freedom to further avoid adverse effects on seafarers’ wellbeing.

On the other hand, lack of enforcement and lack of effectiveness of existing instruments, which do not regulate the concept of seafarers’ wellbeing completely, make the situation even worse. MLC 2006 turns out to be incomplete in terms of not fully capturing all dimensions of wellbeing in its regulations. Yes, various organizations tend to raise awareness most notably emphasizing mental health. However, it is notable to say that mental health has become a kind of measuring tool covering the whole concept of wellbeing, perfectly suited to the industry’s agenda and stigmatizing seafaring as a profession.

Written by Capt. Badri Tetemadze, AFNI

Master / Columbia Shipmanagement Ltd, Research assistant, World Maritime University / MSc Maritime Affairs – MSEA , World Maritime University.

The views presented are only those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of SAFETY4SEA and are for information sharing and discussion purposes only.

Footnotes

1. WHO 1948 definition to health: ‘A state of complete physical, social and mental well-being, and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.

2. MLC 2006 regulation 1.2 requires every seafarer to go through a medical examination prior joining the ship.

3. Maritime Labour Convention 2006 serves as the single regulatory mechanism governing seafarers’ wellbeing at sea.

4. Most of the seafarers report impossibility to maintain the MLC 2006 regulation 2.3 – hours of work and hours of rest without adjusting. In other words in reality, they sleep much less and work more than recorded in their monthly reports.

5. Shipping companies are required to develop SMS onboard of their managed ships as per the ISM code.

6. ‘A flag of convenience ship is one that flies the flag of a country other than the country of ownership’ – https://www.itfglobal.org/en/sector/seafarers/flags-of-convenience