In its latest Safety Digest, the UK MAIB shared the events of an incident involving a historic vessel which struck the dock wall after chief engineer’s mistake to operate the engines ahead instead of astern. MAIB noted that maintaining vigilance without distractions is vital when operating propulsion machinery manually.

The incident

It was a fine summer’s day and a historic passenger vessel was about departure from harbour, but struck the dock wall when the engines were mistakenly operated ahead rather than astern. The mistake led the vessel being removed from service for several weeks in order to repair the resultant damage in a dry dock.

The vessel was about to leave the berth, with the master on the bridge monitoring the vessel’s route and the chief officer on the wheel. In the engine room, the chief engineer was operating the engine controls and a crew member was completing the log.

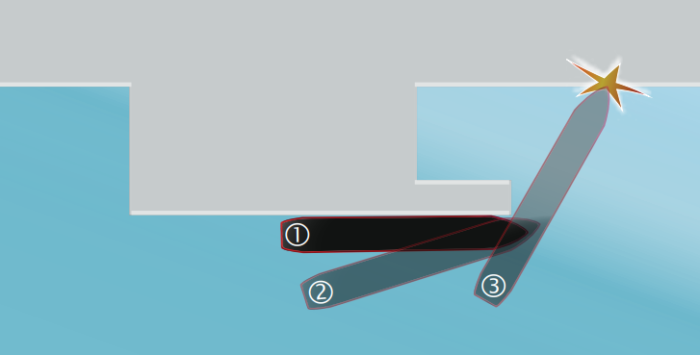

The master’s plan, which he had used many times before, was to drive ahead against the fore spring to bring the stern off the jetty before letting go the remaining lines and making a stern board into open sea. With the first part of the manoeuvre complete and the stern clear of the jetty, the master gave the order for the fore spring to be let go, and rang ‘half astern’ on the telegraph.

Nevertheless, the master noted that, rather than moving astern, the vessel was continuing to move forward. Concerned, he ordered ‘double ring full astern’ (an emergency order). This action had no effect and the vessel continued to move ahead. A further ‘double ring full astern’ was ordered by the bridge, followed swiftly by ‘stop’ on the engine telegraph and a third ‘double ring full astern’. At the same time, the chief officer tried to contact the engine room using the voice pipe, but without success.

In the engine room, while the chief engineer was supposed to operate the engine controls, he was assessing whether a recent engine repair was holding up rather than concentrating on the telegraph. Relying on what he could hear rather than see, he misinterpreted the ‘double rings’, thinking that the bridge required more power – rather than a change of direction from ahead to astern as indicated visually by the telegraph.

The passenger vessel moved ahead rapidly, and it struck the dock wall. The vessel’s engines were stopped and the crew inspected the damage. They discovered that although the vessel’s watertight integrity had not been compromised, it needed substantial repairs. In spite of the fact that this accident occurred on board a historic vessel that had little or no automation, there are lessons to be learned for all bridge and engine room teams. Manoeuvring vessels in confined waters is a hazardous activity, and effective crew resource management is fundamental to minimizing risk of collisions, contacts and groundings.

- When operating propulsion machinery manually it is essential that both bridge and engine room personnel remain vigilant at all times and closely monitor telegraph orders, machinery position indicators, dials and gauges. Concentrate on the task in hand and avoid distractions.

- When given an engine order or a course to steer, that order should be repeated back to ensure that it has been properly received and understood. Furthermore, once the order has been actioned, the new setting should also be reported back. This will not only confirm the engine room team have taken the correct action, but it will also help the bridge team to identify when an erroneous order has been given or an order has been received in error.