State support packages are helping the shipping industry to deal with the COVID-19 crisis. Government support comes in many forms but usually without strings attached and rarely aligned to broader policy objectives, says a new report by ITF.

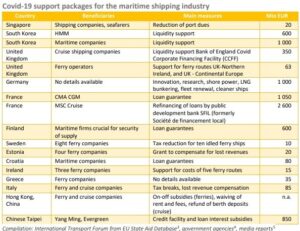

Many governments have put in place additional support measures for shipping, on top of the broadly aimed support to mitigate the overall economic fallout from the Coronavirus crisis, including instruments that could have significant impact on the shipping sector such as changes in the terms of export credits. At least 13 countries have implemented state support for the shipping sector in recent months, according to a preliminary inventory of support packages compiled by ITF.

Cruise companies benefit from aid in the United Kingdom, France, Hong Kong (China) and possibly in Germany in the near future. France, South Korea and Chinese Taipei also provide support to their container shipping companies. Support packages in other countries target the entire shipping sector, not one particular segment.

Schemes diverge substantially in their majority. For example, the Estonian scheme allows compensation up to 80% of the revenue foregone of four ferry companies (granting EUR 20 million), whereas the Swedish scheme provides EUR 9.5 million for ten ferry companies to compensate for wage-related costs, estimated to be 10 to 20% of their forgone revenues.

Most support packages provide liquidity support in the form of loan guarantees and “free liquidity” from state banks. Most of the liquidity support is made available to very large shipping companies with high levels of debt acquired before COVID-19. Various countries have also temporarily reduced port fees.

Aid schemes usually include safeguards to avoid that companies will be overcompensated. Beyond that, however, governments rarely impose conditions designed to achieve public policy objectives other than the immediate goal of mitigating economic losses for the shipping sector due to COVID-19.

Like aviation, the large majority of support measures for shipping include no conditions on economic, social or environmental objectives. Most countries do not even report on the impacts of their maritime state aid scheme

says the report.

In the European Union, 22 countries levy a tonnage tax from shipping companies – a sector-specific and generous tax regime that can replace the corporate income tax. Yet only Norway and Portugal have a tonnage tax scheme that includes incentives to improve the environmental performance of ships, and only the United Kingdom requires recipient shipping companies to train seafarers.

The lack of conditions for support received also applies to other shipping policies. The European Union exempts liner shipping companies from EU competition regulation, known as the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation. This stipulates that the whole transport system should benefit from the exemption, but in practice the European Commission has limited its scope to price reductions for customers, rather than any wider goals, such as connectivity, reliability and sufficiently regular services.

State aid for the maritime sector during the COVID-19 pandemic mitigates the negative economic impacts of the crisis on the shipping sector. Yet it also raises questions regarding the stringency of government policies with respect to desired outcomes. The following insights could serve as starting points for a review of the policy framework for maritime shipping:

- Intensify the monitoring of competition: The level of consolidation and cooperation in segments of the shipping industry makes possible effective collusion to reduce competition. The recent joint efforts of container lines to eliminate capacity through a coordinated strategy of blank sailings raises many questions of concern to competition authorities and merits investigation. Liner shipping requires continuous monitoring and corrective action when inappropriate behaviour occurs. The freedom granted to liners by the EU’s Consortia Block Exemption Regulation to manage capacity jointly and to exchange information is prone to abuse.

- Widen the scope of shipping competition policy: Maritime competition policy has often been narrowly focused on the price for customers. It should also take account of market power vis-àvis suppliers and a wider set of indicators related to service quality, connectivity and environmental performance. A call for proposals on greening competition policy and state aid recently announced by the European Commission24 should be used to start greening the EU Maritime State Aid Guidelines, the tonnage tax and the Consortia Block Exemption Regulation. An alternative to widening the scope of shipping competition policy would be to loosen the restrictions on state involvement in companies.

- Create a global level playing field in maritime state aid: Including shipping in Pillar 2 of the Global Anti-Base Erosion Proposal (“GloBE”) of the G20/OECD would help to create a universally applicable set of rules and comparable conditions for the sector. The proposal foresees a minimum tax for multinational enterprises that would eliminate the incentives for tax avoidance and set the bottom for global tax competition. If the shipping industry should not be included in GloBE, international negotiations on maritime subsidies and tax exemptions ought to be initiated. At the regional level, more active initiatives for tax convergence could be launched. In the EU, the Maritime State Aid Guidelines with regard to the maximum permissible subsidies and tax exemptions could be clarified and more rigorously applied.

- Tackle market distortions resulting from state aid for the maritime sector: Competition authorities should avoid taking decisions that distort markets, as happened with the European Commission’s approval of tonnage tax schemes that cover cargo handling in ports. This has resulted in undue advantages for vertically integrated shipping groups and should be corrected.

- Focus maritime state aid on strategic supply chains: State aid for shipping has proliferated over past decades. Often, expansion of aid has not been driven by objective assessments of potential benefits for the provider. Maritime sector support should be targeted more strategically to help achieve broader objectives than mitigating losses for recipients. The Finnish Covid-19 package provides an example by linking state aid to the policy objective of supply security.