The German Bureau of Maritime Casualty Investigation (BSU) released its report on the grounding of the bulk carrier RUBINA on the River Weser, on 27 August 2020.

The incident

On the evening of 27 August 2020, the Portugal/Madeira-flagged bulk carrier RUBINA was outbound on the River Weser in manoeuvring mode. The ship was sailing from Bremen, Germany, to Houston, United States, with a cargo of steel. A pilot was on board, both steering gears were running, and a helmsman was steering using the hand wheel.

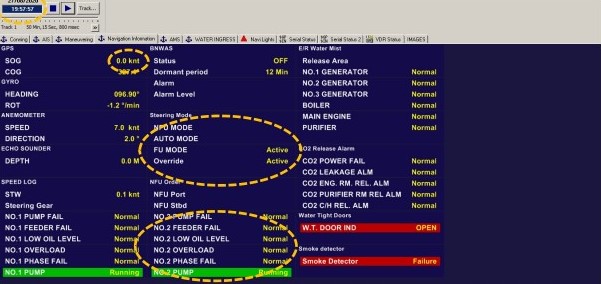

At around 2154, the helmsman tried to return the rudder to midships from a rudder angle of about 15° starboard. Initially, nothing happened, despite a correct had steering wheel position; the rudder remained at 15°. The helmsman immediately reported the problem to the pilot and the ship’s command. After about three seconds, the steering control system automatically switched into so-called “override”5, accompanied by a clearly audible alarm.

[smlsubform prepend=”GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!” showname=false emailtxt=”” emailholder=”Enter your email address” showsubmit=true submittxt=”Submit” jsthanks=false thankyou=”Thank you for subscribing to our mailing list”]

At the same time, the rudder angle changed further to starboard to the hard-over angle of 45°, where it remained. As events unfolded, more helm orders were issued to the helmsman at the hand wheel, who continued to try and steer. However, the rudder failed to respond.

With the hard-over rudder angle, ship’s rotation accelerated even more strongly, at times to a ROT7 of almost 60 °/min. The RUBINA’s speed was about 8 kts at that point.

A general steering gear alarm sounded shortly afterwards. This showed as ‘Steering Gear No. 2 Hydraulic Pump overload’ in the engine control room.

A member of the engine department investigated the alarm and “noted abnormal noise from the pressure relief valve of hydraulic pump no. 2.” In addition, the associated pressure gauge “was found overpressed” (needle at the stop, outside of scale) and a minor, unspecified damage was reported.

After the master and chief engineer had briefly consulted over the phone at 2155, the steering gear was switched to local control directly at the unit (a form of emergency steering) and the magnetic valves on the steering pumps were operated manually. This made it possible to return the rudder to the midships position.

The pilot had immediately ordered full astern and requested a tug. At the same time, the master had issued orders to prepare to drop an anchor. However, this did not happen.

The RUBINA’s prow ran aground outside the fairway before any of these immediately initiated measures could have any effect (at about 2157). Rudder control was regained almost at the same time. Luckily, the grounding occurred in a relatively ‘harmless’ position on the river: at the mouth of a Weser tributary (the so-called ‘Rechter Nebenarm’) and outside the fairway, roughly level with Sandstedt. About two and a half minutes had passed since the rudder had jammed.

Analysis

After speaking to the service engineers, reading the service reports, and reviewing the VDR data, the BSU has arrived at the following conclusion with regard to the course of the accident:

- Since no faults were found on the automation side, a mechanical problem must have caused the accident.

- The pilot valve of pump no. 2 apparently stuck in an open position for a while due to a small contamination. Briefly, it remained fully open and pumping to the starboard side.

- With the steering gear in FU mode, the closed-loop control tried to adjust the rudder angle. The jammed valve, however, ‘disregarded’ any signals, and its pump unit pumped to starboard at full capacity. The closed-loop control tried to compensate for this using the other pump unit, making it pump in the opposite direction. Both pump units reached an equilibrium at a rudder angle of 15° starboard (‘hydraulic blockage’).

- The closed-loop control was unable to compensate for the system deviation between target = ‘rudder midships’ and actual = ‘rudder 15° starboard’. The automation system’s emergency mechanism engaged after three seconds and activated the override, which was accompanied by the Steering Failure Alarm.

- The override activates the NFU mode and deactivates the closed-loop control. In NFU mode, the steering pumps are only set in motion when activated by the tiller.

- The BSU does not think that this happened. The fact that helm orders were still being given – even though the hand wheel has no effect as long as an override is active (even with a functioning steering gear) – proves this, as do the recordings in the VDR of continuous hand wheel rudder orders.

- The functioning pump unit stopped pumping as soon as the override became active, as is technically intended, because the closed-loop control was no longer controlling it. Meanwhile, the defective one continued to pump to starboard at full capacity (even though it, too, was of course no longer being controlled).

- The rudder therefore moved further to starboard from the moment the override was active.

- Since the stuck valve did not respond to electronic inputs, it ignored the electronic rudder angle limit of 35°. This caused the RUBINA – sailing faster than 5.1 kts at that point (about 8 kts) – to turn violently.

- The pump with the stuck valve did not stop pumping even after it had reached the mechanical limit of 45° (hard starboard). The pump kept pumping against a resistance, which led to considerable overpressure, then went into overload and triggered the associated alarm.

- Manual operation of the pilot valve evidently moved the suspected contamination, and the steering gear was fully functional again after that.

Conclusions

The service engineers, crew, and shipping company made every effort to find the fault and prevent a similar event from happening again in the future. By completely replacing the steering pump with the stuck valve, more was done than was indicated, based on the findings of the troubleshooting.

During the accident, all involved essentially behaved correctly. The rapid announcement of the problem by the helmsman enabled immediate action by the ship’s command and pilot, for example. The pilot ordered a tug within short notice. The master’s instructions to prepare the anchors quickly and the rapid changeover to emergency steering directly at the steering gear are further excellent examples of targeted action despite the stressful situation and in the midst of a multitude of alarms.

The safety checks directly after the grounding were carried out systematically and to an appropriate extent.

The handling of the steering modes is the only exception here. Despite the active override, helm orders were still issued to the helmsman at the hand wheel, even though they could not have had any effect whatsoever in the given situation.

Similarly, the exact procedure for resetting the override on this manufacturer’s systems was apparently unknown, as no attempts were made to switch to NFU and back again.

The fact that a reset was actually attempted, albeit to the wrong mode (‘Auto’), can be seen in the VDR.

However, the BSU believes that it would have had little effect (if any) on the course of this accident if steering with the tiller had continued after the override had activated.

Even then, the rudder blade would initially have deflected to hard starboard. Furthermore, steering with the active input device would not have changed anything about the mechanical cause of the stuck valve. Potentially, it might have been possible to prevent the rudder from moving all the way to the hard-over angle, and possibly a lower rudder angle could have been maintained after that. However, it is more than questionable whether the accident could have been completely prevented – especially since, at best, a rudder angle of 15° starboard could have been restored. The RUBINA may then have run aground a moment later (and only if the situation had been accurately assessed very quickly, and action taken with the appropriate presence of mind). After all, only two and a half minutes passed between the first time the rudder failed to respond and the grounding.

Ultimately, the cause of the technical failure of the steering gear remained unclear. The BSU believes that neither of the parties involved could have influenced any of the circumstances, neither beforehand (servicing and maintenance of the steering gear) nor during the accident itself.