US Government Accountability Office issued a report examining how better supply chain information could improve Department of Transportation’s (DOT) freight efforts. U.S. West Coast ports are critical to the national transportation freight network and global supply chains. Changes in global shipping and disruptions at ports can create congestion and economic hardship for shippers with resulting effects throughout supply chains.

GAO conducted case studies of the three major port regions on the West Coast; interviewed key stakeholders— such as port authorities and state and local transportation agencies—for each region and 21 industry representatives, and evaluated DOT’s freight efforts relative to criteria on using quality information to support decision making

This report addresses:

- how major U.S. West Coast ports have responded to recent changes in global shipping;

- how selected shippers have been impacted by and responded to a recent port disruption, and

- how DOT’s efforts support port cargo movement and whether they can be improved.

Global shipping has changed over the past decade in several fundamental ways as ocean carriers have attempted to reduce their costs. The report outlines the following global shipping changes that can impact how cargo is moved through a port:

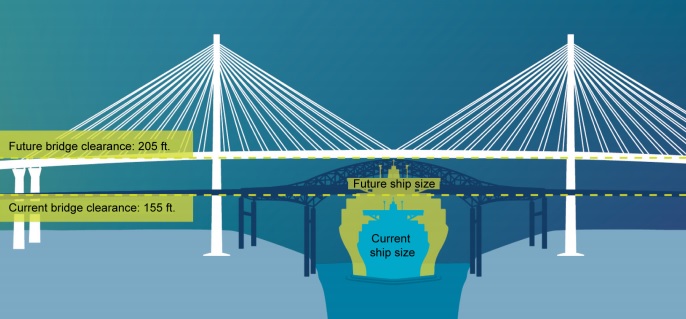

Increased ship size: Over the past decades, many ocean carriers decided to order larger container vessels to meet demand spurred by growing Asian economies, to capture economies of scale made possible by advances in fuel efficient engine technology, and to maintain market share and presence.

Formation of shipping alliances: Ocean carriers have formed alliances as a strategy to contain costs and offer more competitive services. These alliances allow for cargo booked with one carrier to be transported by another alliance carrier’s ship. Shifts in these alliances can result in vessels calling on different ports and terminals, depending on obligations under alliance agreements. There are currently four broad alliances which transport about 80 percent of the U.S. containerized cargo

Changing ownership structures: Historically, ocean carriers owned not only the vessels, but also the cargo containers and the truck chassis that transport containers to and from the vessels. Previously, chassis would be stored, maintained, and repaired (by labor) within the terminal gates. Before leaving the terminal, labor would also conduct a chassis safety, or “roadability” inspection. In an effort to keep their costs low in response to the global recession in 2007-2009 and to follow models of chassis provision in other countries, carriers have divested themselves from chassis ownership and shifted these responsibilities to third-party leasing companies.

GAO report notes that outdated infrastructure can cause constraints on cargo movement, but a variety of terminal and inland projects are under way.

Some port infrastructure is outdated and not well suited to address the recent changes of global shipping. Literature we reviewed and stakeholders we interviewed as part of our case studies described how existing capacity at each of our case study ports could not adequately accommodate larger ships, specifically, and increased volumes, generally. For example, acreage for storing containers within some terminals (i.e. a terminal container yard) was identified as inadequate for handling increased container volumes, though a port may have sufficient acreage across its multiple terminals. Marine terminal operators increase terminal capacity by stacking containers higher, which are then more time-consuming and costly to sort through when a trucker arrives for pick up.

Other infrastructure may be coming to the end of its useful life and need to be replaced or retrofitted to more capably handle larger ships and increased volumes. For example, according to the port authority of Seattle, installing new cranes that can reach across larger vessels would also require sections of one pier to be reinforced to handle the cranes’ heavier weight. Outside ports, aging roadways can also impede cargo movement to and from the port particularly where freight rail, trucks, and other road users converge at congested crossings and intersections. At each of the three case-study port complexes, stakeholders have identified numerous grade crossings, nearby and in the broader metropolitan region, that are problematic for the transport of growing cargo volumes.

A number of terminal and inland infrastructure constraints created or exacerbated by global shipping changes are illustrated in figure below.

Explore more by reading GAO report herebelow

Source & Image Credit: US GAO