Global maritime trade grew by 2.4% in 2023, recovering from a 2022 contraction, but the recovery remains fragile, the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) notes in its latest ‘’Review of Maritime Transport 2024 report’’.

Key chokepoints like the Suez and Panama Canals are increasingly vulnerable to geopolitical tensions, conflicts, and climate change. However, the future remains uncertain. In that regard, achieving more robust, reliable and resilient maritime chokepoints requires maritime transport and logistics to embrace green technologies, digitalization and greater international cooperation.

Maritime chokepoints are defined as critical points along transport routes that facilitate the passage of substantial trade volumes, which serve as vital arteries for global commerce, connecting important regions worldwide. Due to limited alternative routes, disruptions can lead to negative impacts in supply chains and to systemic consequences that affect food security, energy supply and the global economy. For example, in 2021, when the container ship Ever Given ran aground and blocked the Suez Canal for six days, causing around $10 billion in goods per day to be stranded and delayed due to severe congestion.

Key developments in the global shipping fleet

Key developments in the global shipping fleet

#1 Shipping continues to navigate a complex operating landscape

Shipping seems to have found a “new normal” as it continued to cope with the disruptions caused by the war in Ukraine and the legacies of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, increased geopolitical instability and climate-related factors upended shipping in 2023 as ships transiting the Suez and Panama Canals had to be diverted onto longer routes. Attacks on vessels in the Red Sea prompted most shipping lines to reroute around the Cape of Good Hope. At the same time, the Panama Canal had to cut daily ship transits due to drought and low water levels.

#2 In 2023, fleet capacity grew faster than maritime trade volumes; longer routes helped absorb surplus capacity

At the start of 2024, the global fleet was made up of around 109,000 vessels (including cargo and non-cargo ships), each weighing at least 100 gross tons. Global fleet capacity grew by 3.4 per cent, slightly up from 3.2 per cent in 2022. However, this growth rate is lower than the average of 5.2 per cent recorded over 2005–2023, which was driven by rapid fleet expansion during 2005–2012.

Fleet growth was uneven in 2023 with container ship capacity jumping by nearly 8 per cent and that of liquified gas carriers growing by 6.4 per cent. Tanker growth remained low, expanding by less than 2 per cent. The world’s total fleet capacity reached about 2.4 billion dead weight tons, with bulkers making up 42.7 per cent and oil tankers 28.3 per cent of the total.

#3 More ships were delivered in 2023 due to orders placed during the post pandemic boom

In 2023, China, the Republic of Korea and Japan continued to dominate the shipbuilding market with these three countries accounting for about 95 per cent of the global output. This was the first time that China delivered more than 50 per cent of the world’s new ship capacity. The Republic of Korea contributed 28.2 per cent and Japan contributed 14.9 per cent.

#4 Fleet growth was moderate in 2023, with the ship orderbook remaining limited but greener

Although the fuels of the future remain uncertain, the greening of the global orderbook is under way. This includes orders for ships that can use multiple types of fuel and those equipped with dual fuel capabilities, allowing them to use more than a single fuel type.

At the start of 2024, uptake of energy saving technologies continued. Around 50 per cent of the gross tonnage of vessels on order was designed to use alternative fuels, and over 14 per cent was classified as alternative fuel-ready.

LNG accounted for 36.1 per cent of the alternative fuel-capable orderbook while the methanol-capable orderbook, driven by container ships, increased its share to 9.3 per cent, up from 4 per cent at the start of 2023.

Twelve orders for ammonia-capable ships were placed for the first time in 2023, while wind-assisted propulsion attracted more interest. Ports are also expanding their green infrastructure, with 195 ports currently offering LNG bunkering, 77 developing this capability and 28 providing bunkering for at least one other alternative fuel. At least 205 ports provide some shore-side power, with around 2,500 ships currently being fitted with shore power connections.

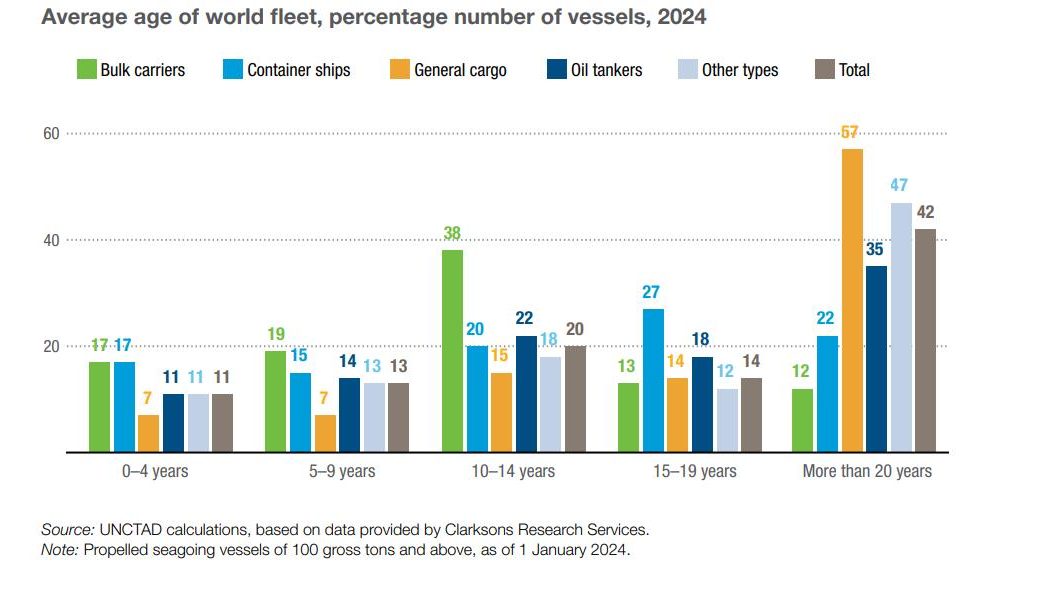

#5 The world fleet is ageing; environmental targets are hardening but progress towards fleet renewal remains slow

In the context of growing decarbonization commitments, as well as a relatively moderate orderbook and restrained investment in newbuilds, global fleet renewal is emerging as a key theme. The global shipping fleet is ageing, with many ships soon due to reach the end of their service. The age of the global fleet by dead weight tonnage at the start of 2024 was 12.5 years; the age by vessel counts averaged 22.4 years, an increase of 2 per cent over the same period in 2023.

Smaller, older ships are contributing to the higher average age. The fleet matured by more than three years compared to the previous decade, and more than half of the fleet by vessel count is now over 15 years old. Average ages of ships went up across all fleet segments, except for container ships, which saw an influx of new vessels in 2023.

#6 Low demolition rates and strong second-hand markets are influencing investment in newbuilds and fleet renewal

A key development in ship demolition activity is the upcoming entry into force of the Hong Kong International Convention for the Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships. Set to enter into force on 26 June 2025, compliance will mean additional expenditure and costs for ship demolition yards. For example, all facilities in India, which accounted for 7.1 per cent of total gross tonnage sold for scrapping in 2023, are currently compliant. In Bangladesh, which accounted for about 46 per cent of tonnage sold for demolition, one third of the facilities are reportedly compliant or in the process of becoming certified.

Although ship demolition activity is currently low, the pace of scrapping is expected to rise in the coming years as the pressure to renew the global fleet intensifies. The fleet of 240 steam turbine LNG vessels offers candidate ships for scrapping, while an end to rerouting around the Cape of Good Hope (the precise timing of which is uncertain) is expected to send more container ships to scrapping yards.

#7 Beyond supply and demand, other factors may be influencing the shipping cycle

Although trade and fleet capacity remain the key drivers of the shipping cycle, other factors can impact the boom and bust cycle. Such factors include, as observed in recent years, an increase in distances travelled caused by ship rerouting onto longer routes. Extended ship journeys and longer distances result in increased ton-mile demand which, in turn, alters the actual supply of ships’ carrying capacity.

Continued regulatory uncertainty around the fuels of the future, together with underlying overcapacity are also at play and are affecting how the cycle operates. Shipbuilding cycles typically follow patterns of expansion and contraction. Freight and charter rates serve as market signals that drive decisions about ordering new ships, putting ships in “idle” or “layup” status, buying or selling ships, as well as demolition.

In the short term, the supply of shipping capacity is inelastic and cannot quickly adjust to changes in demand as it takes several years to build new ships.

#8 Global fleet capacity is predominantly owned by developed economies but mainly flies the flags of developing economies

In 2023, the top 35 flag registers accounted for 94 of the world fleet. Eighteen of the leading registers were from developing economies and accounted for 76 per cent of the world fleet capacity.