10 February marks two hundred years since the birth of Samuel Plimsoll, the great maritime safety campaigner and Member of Parliament who fought for the introduction of the load line that still bears his name.

As a book charting the course of his campaign to save lives at sea is reissued to mark the occasion, we spoke to the author, Nicolette Jones, about why his story is still relevant to maritime safety professionals today.

SAFETY4SEA: What first got you interested in Plimsoll?

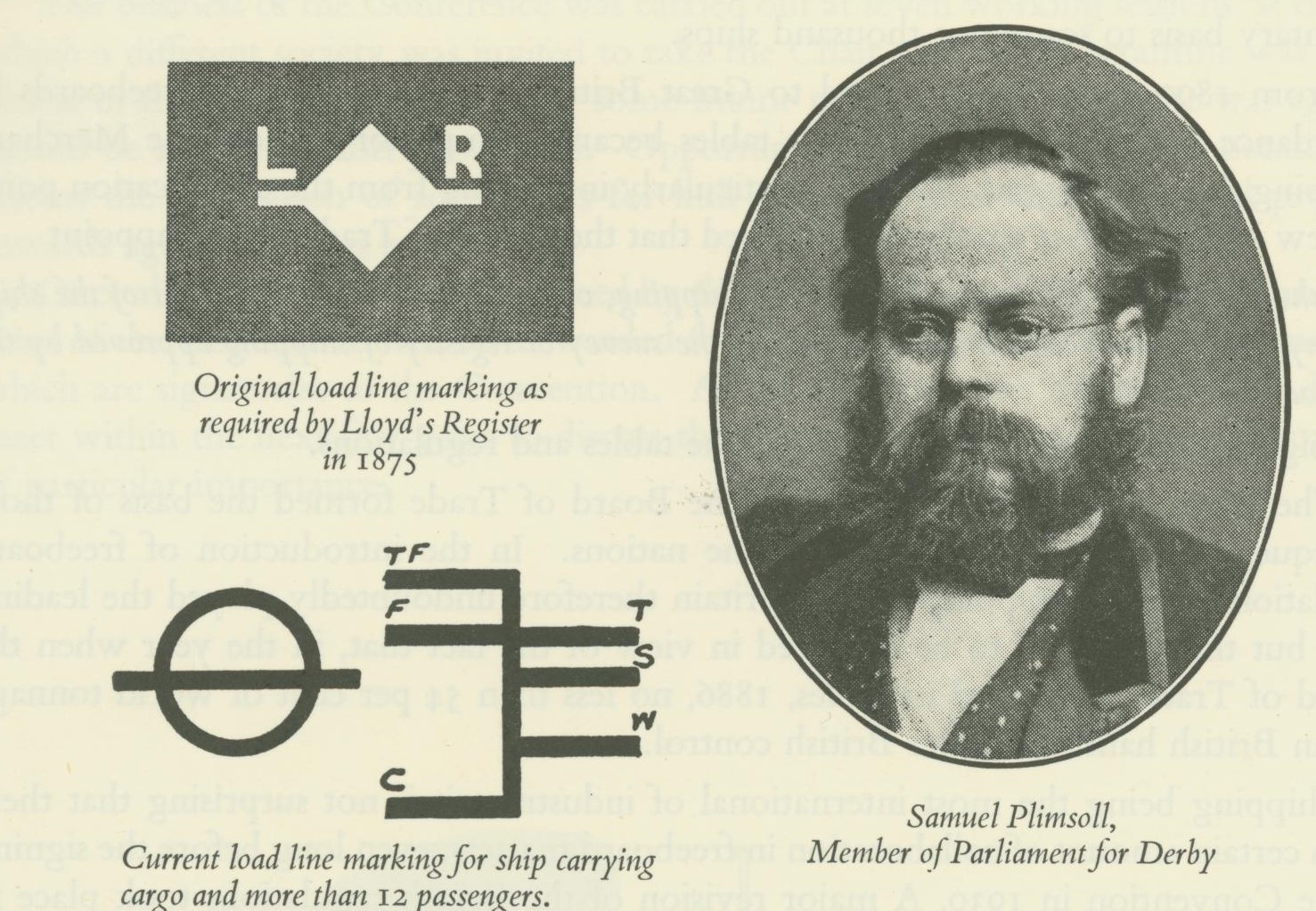

Nicolette Jones: I was first alerted to Samuel Plimsoll when I moved into a house on Plimsoll Road in London. A few doors down was a pub whose sign had a red baseball boot stuck in the middle, with, around the edges, a bit of grey sea. When the pub changed its name, and the sign was taken down, I bought it on a strange impulse, curious about what it revealed about the name of the street. It is now in my back garden. Under the sticker was a ship (circa 1960), with the Plimsoll mark on its side and its seasonal loading levels – TF, F, S, W, WNA – as well as the ‘LR’ mark of the Lloyd’s Register maritime classification society. Also on the sign were Samuel Plimsoll’s name, and dates of birth and death – 1824-1898. This unprepossessing sign led to years of obsessive research, and allowed me to get to know stroppy, unstuffy, dauntless, empathetic Sam and the story of his great whistleblowing fight for justice, which still resonates today.

S4S: Why is the Plimsoll story still relevant to maritime professionals and safety practitioners today?

N.J.: Despite the mounting losses of ships and lives attributable to overloading at the time – the British Board of Trade reported that in 1871 a total of 856 ships went down within 10 miles of the British coast in conditions that were no worse than a strong breeze, and that overloading and unseaworthiness caused some 500 seamen a year to drown – Plimsoll had many opponents in his campaign to have a safe load line introduced and respected. Many of the 19th-century arguments against the load line would be familiar to anyone trying to introduce standardised measures today, whether for the health and safety of crew and passengers, or to protect the environment. These arguments included, for instance, objection to red tape, disadvantage in the face of competition, and the inconvenience of change. The truth was these objections were often motivated by vested interest. Load line breaches still occur today – European and Canadian authorities reported 3,197 breaches as recently as 2005 – and for similar reasons. The enduring relevance of the Plimsoll story, then, lies in a timeless underlying principle, which applies both at sea and on land: that in any enterprise where the people who make the profit are not those who take the risk, there is always a tendency for commercial pressure to increase that risk. Modern examples of suffering caused by such circumstances are not hard to come by. We could still keep Plimsoll busy today.

S4S: What are the key things we can learn from Plimsoll?

N.J.: As one of the pioneers of the social shift we might characterise as ‘the industrial revolution finding its conscience’, Plimsoll demonstrated a number of truths we now often take for granted, but sometimes need reminding of: that public opinion can drive change, and it is always a good idea to get the media on your side. That persistence is crucial. That a moral issue is often quite simple, however complicated debate becomes. Of course, that power comes with responsibility. And, above all, that the world can be a better place if we take it upon ourselves to act when we see danger to others and do not leave action to someone else. Plimsoll was incapable of walking by on the other side.

S4S: What most inspires you about the Plimsoll story?

N.J.: We tend to hear most, both in history and in the news, about individuals who change the course of events for the worse. I think it is truly important to remember lives that are landmarks in increasing the common good. I include in this Plimsoll’s wife Eliza, who was a catalyst at all significant points in his campaign for seafarers, and an equal partner in the cause. As with many women in the course of maritime history, her contribution is one that is all too often overlooked – although that is thankfully starting to change thanks to initiatives such as the ‘Rewriting Women into Maritime History’ programme being led by the Lloyd’s Register Foundation Heritage and Education Centre. Although the Plimsolls became national heroes in Britain, cheered by crowds and lauded in prose and song, together they also endured vilification by detractors, the deterioration of their health, relentless demands on their time and a drain on their pockets. They are still an example of courage and fortitude.

S4S: Where do you see the Plimsolls of today? Who is taking forward his legacy?

N.J.: There are people today who grapple with injustice and won’t let go. In the UK, this includes modern day parliamentarians such as David Lammy, working for the families who lost relations in the infamous Grenfell Tower fire. It also includes figures further from power such as Alan Bates, who has led a tenacious fight for compensation for hundreds of his fellow sub-postmasters, falsely accused of theft and fraud by the British Post Office. Sometimes, however, it is whole organisations who are required to take a stand. In the maritime world, bodies such as the International Maritime Organisation and the various shipping registers have inherited Plimsoll’s mantle as guardians of the safety of seafarers, and indeed of the planet. Lloyd’s Register’s website, for example, declares its principles: “we care about the safety of everyone”. Samuel Plimsoll would have approved.

S4S: What is the key message you hope readers will take away from the book?

N.J.: As is usually the case with whistleblowers, there were people who doubted Plimsoll’s usefulness or questioned his methods, and on some points they may have been right. But his doggedness came from the certainty that lives were endangered and families bereaved because there were people who did not care enough about those lives and families. The key message, I think, is: we should care.

The views presented are only those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of SAFETY4SEA and are for information sharing and discussion purposes only.

I’m really pleased that Nicolette Jones book is being republished. It deserves attention, not least because it refers to Mrs Eliza Ann Railton Plimsoll, Samuel’s co-campaigner and wife (1830-1882), and the Ladies Committee involved in the Plimsoll campaign. It’s important to remember that the maritime past was changed by women’s contributions, even if they weren’t allowed to go to sea.

When I was 11 we had an inspiring teacher, Miss AB Mountain, who read us stories of people we might one day emulate. The Plimsolls were stars among these, along with the cats’ eyes man. The kind intentions driving such innovators have warmed me all my life. Thank you.