Stable Seas published its latest report on the risk of maritime radiological and nuclear trafficking by small, traditional and unregistered vessels.

The purpose of the report is to provide a high-level overview of the potential risk of maritime smuggling by small, traditional, and unregistered vessels (STUVs) across four marine regions: Brazil, West Africa (including littoral states from Cabo Verde to Nigeria), the Red Sea (including Egypt, Sudan, Eritrea, Yemen, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel), and Indonesia.

Maritime radiological and nuclear trafficking using small, traditional, and unregulated vessels (STUVs) is an inherently low-probability, high-consequence threat. Known instances of R/N smuggling are relatively uncommon, those known to include maritime trafficking are rarer still.

However, the consequences of even one successful incidence of maritime R/N trafficking has the potential to have far reaching and tragic consequences. In light of the potential consequences, this report seeks to shed light on the potential risk of maritime R/N trafficking using STUVs in particular.

The first section of the report will provide broad context regarding the unique risk of radiological and nuclear (R/N) trafficking via STUVs.

Subsequent sections focused on each region will provide a summary of the maritime security context, prominent trends in maritime trafficking of all kinds, the regional capacity for addressing maritime trafficking concerns, and an assessment of risk factors which may contribute to the potential for maritime radiological and nuclear trafficking.

The final section of the report will seek to identify recuring gaps across regions and potential policy recommendations for those engaged in efforts to mitigate the risk of R/N trafficking via STUVs.

…there has been a total of 3,686 instances of R/N material out of regulatory control between 1993 and 2019, an average of 136.5 per year over the 27 years of available data

says the report.

Brazil

First, Brazil does appear to see some levels of maritime trafficking in wildlife and arms. Arms appear to be the most significant of the two, with major inbound flows that fuel organized crime.

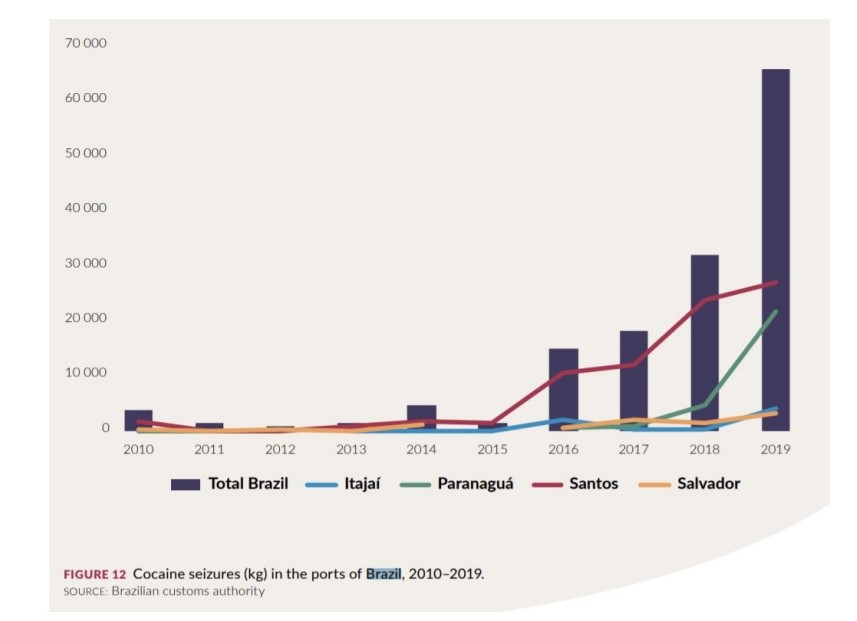

However, the most prominent form of maritime trafficking in Brazil is drugs, predominantly cocaine, as Brazil has emerged as perhaps the largest single point of disembarkation of transatlantic cocaine trafficking to West Africa and Europe.

…Brazil has emerged as perhaps the largest single point of disembarkation of transatlantic cocaine trafficking to West Africa and Europe

noted the report.

However, these figures for containerized drug traffic likely do not illuminate the entire scope of Brazil’s transatlantic drug trafficking activity, as several forms of STUVs (including fishing vessels and sail boats) operating in Brazilian waters also appear to be increasingly involved.

A second, but more difficult to confirm modus operandi involving fishing vessels may entail shorter routes to points within or just outside of the Brazilian EEZ for transshipment to other vessels which then complete the transatlantic route.

Another, less prevalent but still noteworthy, type of STUV of potential concern in Brazilian waters is sailboats and recreational vessels more broadly. In 2020, a sailboat from Portugal was discovered off the coast of the northern port city of Recife with 4.3 tons of drugs.

Assessment of key factors:

- Presence of state or non-state actors potentially seeking nuclear materials

- Presence of legacy stockpiles or natural resources associated with nuclear/ radioactive supply chain

- Presence of existing maritime smuggling networks

- Prevalence of STUVs

- Level of maritime domain awareness and maritime enforcement capacity

- Strength of systems for vessel registration and monitoring

- Perceived levels of corruption or lack of capacity in port and customs authorities

- Level of economic in coastal communities

West Africa

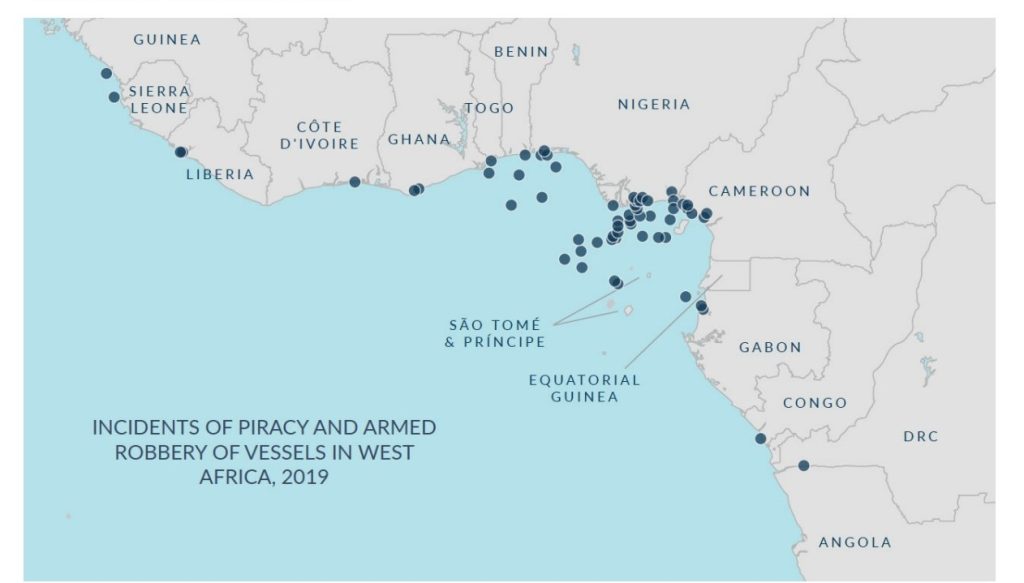

Of the diverse maritime security threats facing the region, perhaps the most well-known is piracy and armed robbery. West Africa (particularly Nigeria) and adjacent areas of Central Africa are now the most prominent global hotspot for maritime piracy, armed robbery, and kidnap for ransom.

In addition to piracy and armed robbery, another major maritime security challenge in the region is the prevalence of illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. Studies on the severity of IUU fishing vary in time frame, scope, and methodology, but generally speaking, IUU fishing activity has been estimated to represent up to 40%, or even 65% of the total catch in the region.

In addition to these other forms of maritime crime, maritime trafficking itself is also a significant challenge. A number of factors exist which create a facilitating environment for maritime trafficking in the waters of West Africa, including:

- Poverty and unemployment in coastal communities which can incentivize a turn to participation in maritime trafficking

- Generally underdeveloped maritime domain awareness and maritime enforcement capacity in regional states

- Port monitoring and security at formal ports that leave gaps for traffickers to exploit

- Levels of corruption in both port and customs agencies and broader government which facilitate maritime trafficking activity

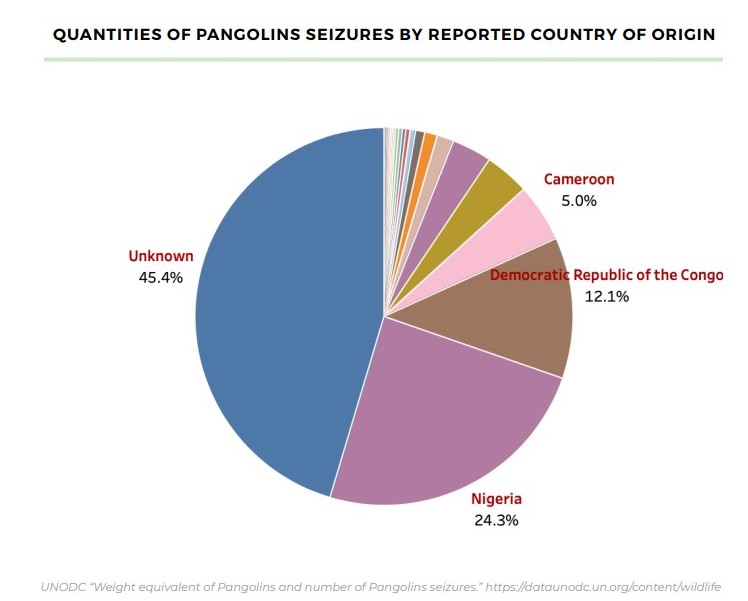

All of these factors combine to make West Africa a global hotspot for trafficking in a variety of illicit goods including arms, illicit wildlife products, and drugs.

Another problematic form of trafficking in the region with much clearer links to the maritime domain is the illicit trade in wildlife products including pangolin, ivory, and illicit timber.

Finally, maritime drug trafficking is perhaps the most relevant form of maritime trafficking in West Africa for the purposes of this report. Several types of drugs present challenges in West Africa but most are of limited relevance to the issue of maritime trafficking, particularly by STUVs.

Finally, cocaine is perhaps the most relevant form of maritime drug trafficking as it pertains to STUVs specifically. In addition, maritime cocaine trafficking appears to involve the most significant participation of STUVs of any form of trafficking in the region.

Assessment of key factors:

- Presence of state or non-state actors potentially seeking nuclear materials

- Presence of legacy stockpiles or natural resources associated with nuclear/ radioactive supply chain

- Presence of existing maritime smuggling networks

- Prevalence of STUVs

- Level of maritime domain awareness and maritime enforcement capacity

- Strength of systems for STUV registration and monitoring

- Perceived levels of corruption or lack of capacity in port and customs authorities

- Level of economic security in coastal communities

Red Sea

One of the maritime security issues on the Red Sea which has garnered the attention of policy makers across the globe is the threat of maritime terrorism. Maritime terrorism in the Red Sea poses a variety of threats to both military and civilian vessels including the use of mines, anti-ship missiles, and unmanned attacks by remote controlled boats and aerial vehicles.

Posing a very different kind of challenge, the Red Sea and adjacent Gulf of Aden have become one of the globe’s most significant hotspots for dangerous maritime mixed migration.

In addition to this route between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula, there also appears to be significant migration across the Red Sea itself, particularly between the Arabian Peninsula and Sudan.

All of these patterns and routes are multifaceted and continually shifting based on a variety of factors, but it is clear that there is a complex network of maritime migration routes across the broader region.

Finally, maritime drug trafficking also appears a significant concern in the Red Sea. In the broader region, well known trafficking routes originating in Afghanistan and the Markan Coast move heroin through the Western Indian Ocean via dhows, and while the majority of this traffic appears to travel down the East African littoral, there may also be ancillary branches moving through the Red Sea, particularly to Egypt.

In addition to heroin, maritime trafficking of captagon also appears increasingly prominent in the Red Sea.

Assessment of key factors:

- Presence of state or non-state actors potentially seeking nuclear materials

- Presence of legacy stockpiles or natural resources associated with nuclear/radioactive supply chain

- Presence of existing maritime smuggling networks

- Prevalence of STUVs

- Level of maritime domain awareness and maritime enforcement capacity

- Strength of systems for STUV registration and monitoring

- Perceived levels of corruption or lack of capacity in port and customs authorities

- Level of economic and physical security in coastal communities

Indonesia

Indonesia’s maritime security context is characterized by complexity. It has a vast and varied maritime domain and an equally complex set of maritime security challenges to contend with. Its vast archipelagic geography spans roughly 5,000 kilometers from east to west and includes more than 14,000 islands and the second longest coastline in the world,186 generating an EEZ of more than 6 million square km.

Perhaps the most pressing of these on a day-to-day basis is IUU fishing. Both foreign and domestic fisheries crime is a massive challenge for Indonesia and one that is estimated to cost it roughly $4 billion annually.

Quite different from fisheries enforcement, Indonesia must also contend with the use of the maritime space by violent nonstate actors.

Perhaps the most attention-grabbing maritime security challenge faced by Indonesia however is piracy and armed robbery, of which Indonesia is the epicenter in Asia. In 2020 the Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (ReCAAP) recorded 97 piracy and armed robbery incidents in Asia.

Finally, maritime trafficking is also a significant challenge in Indonesia given is vast and sometimes porous maritime borders. The primary products trafficked through Indonesia’s maritime domain appear to be synthetic drugs and illicit wildlife products. In terms of synthetic drugs, Indonesia sits directly along the maritime routes which traffickers use to move synthetic drugs from production centers in mainland Southeast Asia to consumers in Oceania and East Asia.

In addition, given its biodiversity and maritime geography, Indonesia has become a hotspot for maritime trafficking of illicit wildlife products. In 2019 Indonesia’s Ministry of Environment and Forestry estimated that the illegal wildlife trade in the country was valued at nearly $1 billion annually.

Assessment of key factors:

- Presence of state or nonstate actors potentially seeking nuclear materials

- Presence of legacy stockpiles or natural resources associated with nuclear/ radioactive supply chain

- Presence of existing maritime smuggling networks

- Prevalence of STUVs

- Level of maritime domain awareness and maritime enforcement capacity

- Strength of systems for vessel registration and monitoring

- Perceived levels of corruption or lack of capacity in port and customs authorities

- Level of economic security in coastal communities

Concluding the report, there are significant challenges facing actors who seek to reduce the risk of R/N trafficking via STUVs.

These vessels operate with relative anonymity and many of the states of greatest concern have very limited capabilities for understanding their movements and any potential R/N trafficking.

Countless such vessels operate across the globe, blending into the frenetic activity of coastal waters and avoiding the scrutiny of formal ports. While progress has been made in some areas in recent years, states around the world are still very far from having a complete picture of their activities and their potential for R/N trafficking.

There are however several areas where sustained policy attention and investment could yield significant progress in countering potential R/N trafficking by such vessels. Several such areas identified in the course of this research include:

- STUV Monitoring

- Human Intelligence

- Informal Port Monitoring

- Coastal Economic Security