In the previous articles, Green-Jakobsen discussed the difference between Work as Imagined and Work as Done. They touched upon three key principles that can help improve performance: the context-dependence of human performance, the acknowledgement that performance transcends individual efforts, and the necessity of reviews, particularly from a team perspective. They also discussed the performance wheel, proving that we need to see performance as a process instead of an end-product.

In this article, Green Jakobsen will delve a bit deeper into the specific example of a finding that impacts performance. They will also discuss the practical lessons that we can draw from such performance data.

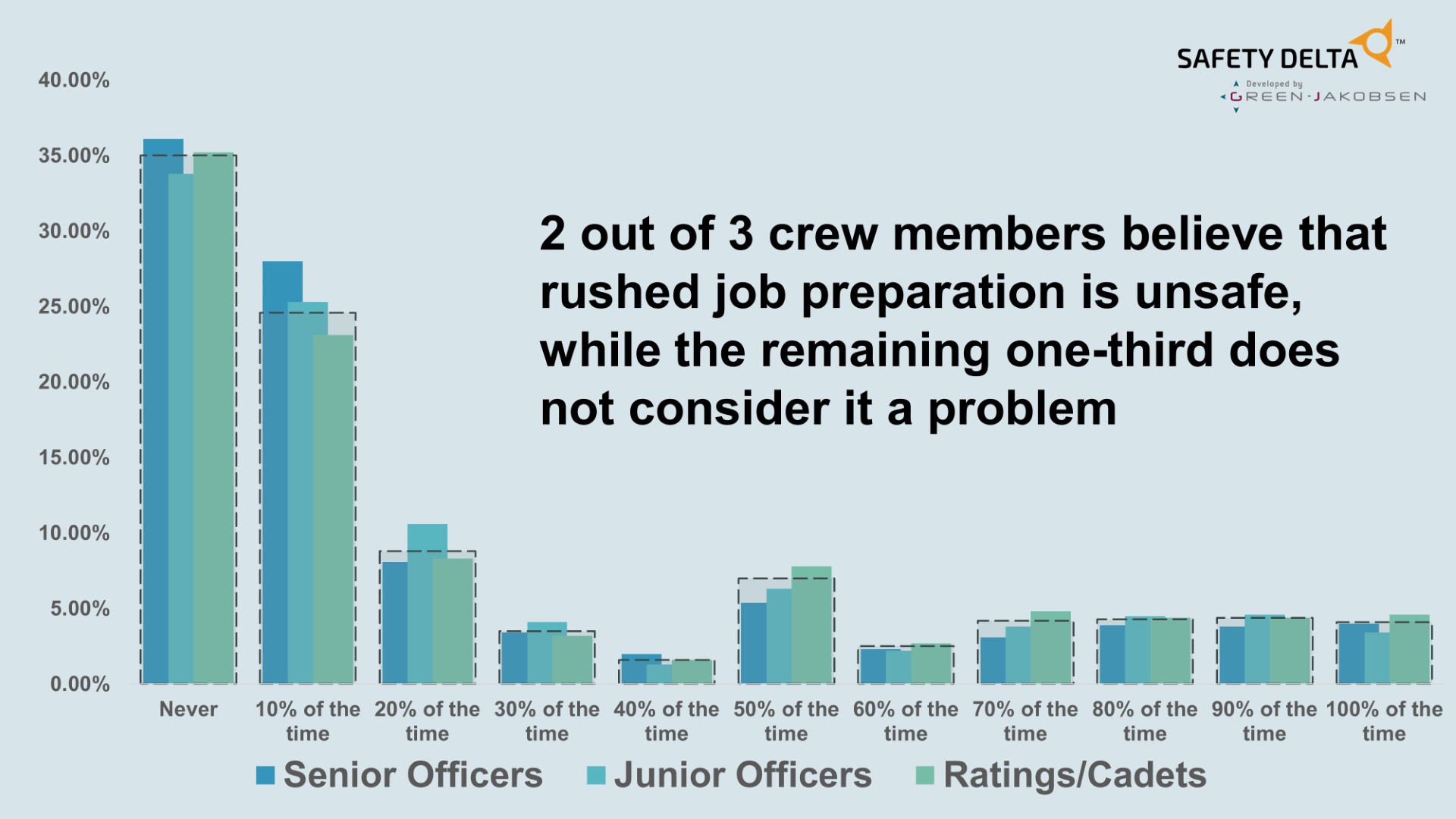

“Rushed job preparation is safe – ?!”

Let’s look at some data from SAFETY DELTATM . In our Crew Safety Diagnosis Survey, we asked how often rushing job preparation leads to unsafe execution. Out of 30,000 responses, one-third, including both senior officers and crew, answered ‘Never’.

Data like this shows widespread belief among the crew that rushed job preparation never leads to unsafe job execution. Take a moment to reflect on the possible consequences of this. You may consider these two critical questions:

Data like this shows widespread belief among the crew that rushed job preparation never leads to unsafe job execution. Take a moment to reflect on the possible consequences of this. You may consider these two critical questions:

1. Does it imply a breakthrough in operational efficiency?

- Is the outlook among senior officers and crew members a sign of significant improvements in operational efficiency?

- Are there any new approaches or streamlined processes contributing to this perception?

OR

2. Does it indicate hidden problems?

- Conversely, could this shared mindset conceal underlying problems, possibly masked by a perception of flawless execution?

- Are the risk management procedures in place effectively serving their purpose, or are they perceived as not useful at all?

What kind of mindset is that?

Seen from a safety perspective, job preparation—as part of the risk management process—is not optional. The mindset that rushed job preparation is always safe can foster a culture of complacency. The crew may become less vigilant in adhering to safety protocols, assuming that they can bypass certain steps without consequences. This complacency can erode a safety-conscious culture.

The crew may also believe that their experience and skills alone are sufficient to ensure safety, neglecting the importance of collaborative efforts, adherence to safety protocols, and the need for comprehensive job preparation involving the entire team.

What can be done?

One thing is certain, we need to work on the mindset –not only on board the vessels, but also within the organisational culture as a whole.

No doubt, the risk management procedures are up to date, and the crew is most likely well-trained in those. Working on fostering a mindset and creating an environment on board that allows anyone to speak up and contribute to the risk management process – from preparation to execution, and finally, during the essential debriefing stage – can make a great difference. Additionally, to gain the useful insight, for example that the perception exists that a rushed job preparation is ok from a safety aspect, performance must be constantly reviewed.

The senior management team on board can assist in improving this mindset

Our SAFETY DELTATM data, combined with over 20 years of developing human performance, prove that leaders influence the performance of their team members or subordinates, including their safety performance and practices. Leadership is a cornerstone among the key pillars of human performance development, alongside Work Structure, Behaviour, Reviews, and Employee Development.

One of our findings indicates that if on-board leaders communicate about taking risk management procedures seriously and carrying them out more thoroughly, as well as ensuring that everyone is expected to contribute, the crew members will be more engaged and thorough.

A culture of safety begins with leadership

Breaking this mindset commences with giving instructions. Leaders set the tone for the entire team, influencing attitudes and behaviours. When the Senior and Junior Officers communicate instructions to their team members or subordinates, it is crucial to emphasise that safety must always be the foremost priority. In doing so, they guide, motivate, and prepare their subordinates or team to become safety-conscious individuals who exhibit best safety practices, embody good safety behaviours in their actions and decisions, and adhere to safety rules and procedures before, during, and after every task.

While senior leaders have a significant influence, it is important for all levels of the organisation to actively participate in promoting better safety and operational performance and continuously strive for improvement of the psychological safety and the seafarers’ wellbeing.