As China races to meet government targets, its shale gas has grown to nearly 600 wells and 9 bcm of production, over the last year, and Wood Mackenzie consultant projects production to almost double to 17 bcm in 2020.

Sinopec’s Fuling, PetroChina’s Changning-Weiyuan and Zhaotong projects – which sit in the mountainous terrain of the Sichuan Basin – are responsible for a total capital investment of US$5.5 billion. Nearly 700 new wells will come onstream between 2018 and 2020 from the three projects combined, according to WoodMac. However:

Despite commendable achievements in domestic shale, China will still mis-s the 2020 30-bcm production target announced in its 13th energy sector five-year plan by a considerable margin. While China is eager to materialise its shale gas potential to fuel its massive gasification initiative and support rising demand growth, there’s much more work to be done.

To meet the government’s 30-bcm target, China needs up to 725 additional wells by 2020 on top of the nearly 700 new wells, added Dr Tingyun Yang, Consulting. Considering the impact of shale gas production on domestic demand, the 2020 13-bcm ‘gap’ will have to be filled by imports, in particular LNG. The good news is that well costs have gone down considerably – 40% for exploration wells compared to 2010 levels, and 25% for commercial wells compared to 2014.

How does this compare to the US shale story?

The US took more than three decades to finally realise its shale boom. Success was built on a combination of underlying factors, none of which hold true for China:

- competitive and open markets,

- active small players,

- developed infrastructure

- easily available expertise.

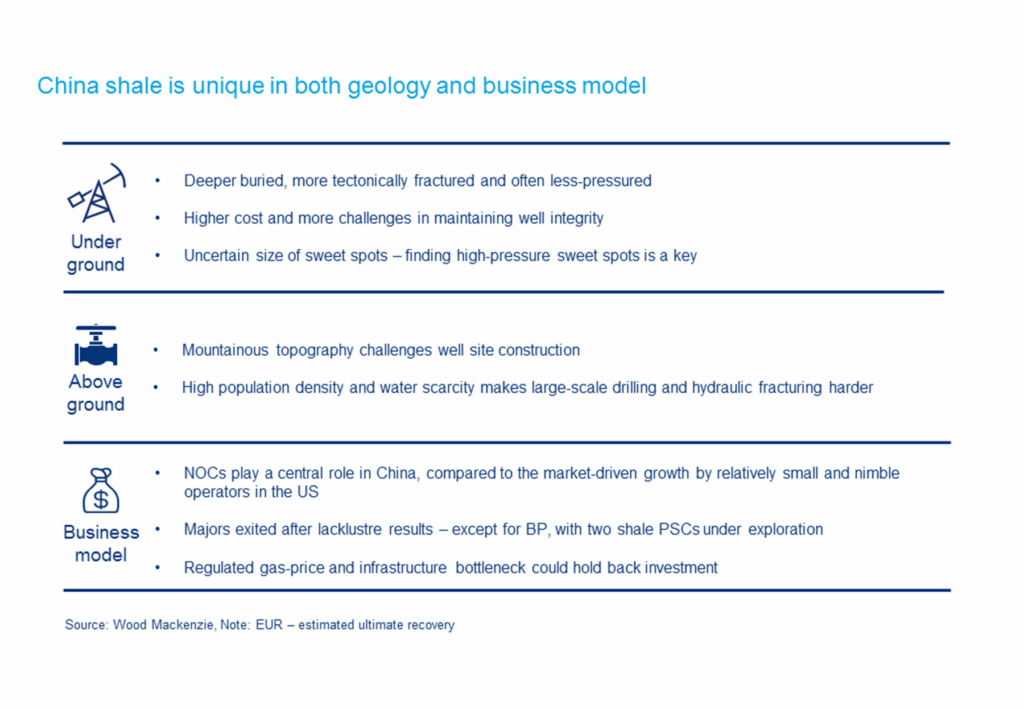

Woodmac identified a few key differences between US and Chinese shale plays:

Who are the main shale players?

- The Majors took a run at China’s vast shale resources during the first few years of the decade, but all exited after lacklustre results. Only BP now remains with two undeveloped shale production sharing contracts.

- The Chinese NOCs, however, have overcome these challenges by developing their own understanding of the unique geology, relying on their own service arms to get more experience and, most importantly, progress in completion techniques and technology.

They have adopted a pad-based drilling, fracturing and production process, which reduces the footprint of the well sites on the mountains. This practice, combined with more indigenous technology and drilling and completion techniques – fracturing trucks, drillable bridge plugs, and drilling trajectory control know-how for example – have helped to save drilling time and reduce costs, while wells are becoming larger.

What about shale well costs?

- While Chinese shale well costs are still much higher compared to US, (even 20% higher compared to a deeper and larger well in the Haynesville) a recent turnkey contract of four Sichuan wells won by domestic Honghua Group, could perhaps hint at a new chapter in Chinese shale. The contract would imply an all-in cost at US$7-7.5 million per well, a further 20% drop in well cost compared to 2017, once pad construction, infrastructure and facilities costs are included.

While we don’t expect a Chinese shale gas boom anytime soon, the NOCs will no doubt continue to push on and innovate, driven by the need to secure and develop energy resources for strategic reasons.