Hydraulic fracturing, also known as “fracking”, the divisive method of extracting natural gas from shale formations, should be approached with caution by countries seeking ways to increase access to energy, according to a new report by UNCTAD, reviewing the history of shale gas extraction in the US and assessing how it aligns with Paris Agreement, in the context of pressing energy needs.

Energy is among the top issues on the international agenda for sustainable development, specially in the light of the recently adopted 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and in particular SDG 7, which aims to ensure affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all by 2030.

The report, a special issue of UNCTAD’s Commodities at a Glance series, seeks to “offer a dispassionate perspective” on shale gas and hydraulic fracturing for policymakers and other stakeholders. UNCTAD Secretary-General, Mukhisa Kituyi, said:

Climate change means that all countries must, as a matter of strategic urgency, move away from burning fossil fuels, including shale gas. But given that energy is needed to end poverty and boost development, countries with potential shale gas resources should understand the pros and cons when they take policy decisions about the short-term energy mix.

On one hand…

The report says investments in the shale gas sector should not be made at the expense of the deployment of renewable energies and energy efficiency strategies, and that gaps in local geological and hydrological knowledge, the lack of a “social license to operate” as well as inadequate regulatory environments may constitute major obstacles to the use of hydraulic fracturing as a method of extracting shale gas.

Natural gas should contribute to fostering a smooth transition from the current economic model, mainly based on fossil fuels, to achieving a low-carbon economy, with the objective of meeting the Sustainable Development Goal 7 by 2030.

The report says that natural gas, including shale gas, offers both advantages and disadvantages as a so-called “bridge” fuel between large CO2 contributors like coal and oil, and renewable energy sources.

A significant advantage is that natural gas emits about 40% less CO2 per unit of energy produced than coal and that it can be stored and used on demand to meet variable energy needs more efficiently than energy generated from renewable sources such as wind.

…on the other hand

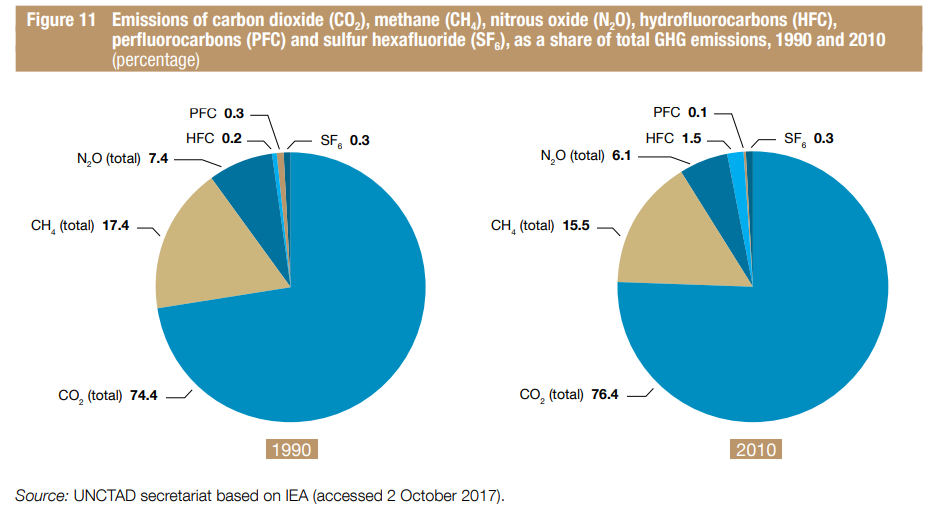

However, the disadvantages include that LNG remains a fossil fuel that emits harmful CO2 when burned. Besides, while the main component of natural gas, methane (CH4), has a shorter atmospheric lifespan than CO2, its global warming potential is 28 times higher than that of CO2 on a 100-year time horizon.

In 2016, methane atmospheric concentration reached a record high of 1,853 parts per million – about 257% of its pre-industrial level – according to the World Meteorological Organization.

Concern has been expressed with regard to the large quantities of water used by hydraulic fracturing, as well as the potential risks generated by shale gas operations, on the quality of such resources through groundwater or surface water contamination.

According to US Energy Information Administration, world Technically Recoverable Resources (TRR) for shale gas were around 215 trillion cubic meters in 2015, equivalent to about 60 years’ worth of world consumption. About half of these resources are located in Algeria, Argentina, Canada, China and the United States.

The US remained the leading shale gas producing country in 2015 with 87% of the world total, and has become a net-exporter of natural gas starting from July 2017.

The UK Department of Energy and Climate Change has earlier proposed recommendations with respect to hydraulic fracturing activities, noting they are focused on three main lines of action, as follows:

–> Before any hydraulic fracturing operations starts:

i. A review of local seismicity should be conducted with the aim of identifying natural faults that could be reactivated by hydraulic fracturing operations.

ii. A pre-injection test, allowing water to flow back, should also be made and monitored prior to any large-scale hydraulic stimulation taking place. 2.

–> Throughout the whole hydraulic fracturing cycle, seismic activity must be carefully monitored.

–> Hydraulic fracturing activities must be suspended as soon as seismic activity exceeds a predefined threshold. The Department of Energy and Climate Change (2012:3) proposes that this limit be fixed at M0.5, a level considered as prudent. This threshold may be revised on the basis of experience gained.

Explore more herebelow: