The heightened focus on energy security and the rising cost of energy is reinforcing the difference in decarbonization speed between Europe and the rest of the world, according to the sixth edition of DNV’s Energy Transition Outlook.

Key highlights

- Heightened focus on energy security and rising prices reinforcing decarbonization difference between Europe and the rest of the world;

- Long term trends of the energy transition remain with rapid rise of renewables and growing electrification outweighing short term shocks;

- Growing and greening of electricity production remains the driving force of the transition, with renewables accounting for 83% of electricity production by 2050;

- One year on from UN Secretary General António Guterres’ Code Red warning on climate, emissions remain close to record highs putting world on course to warm 2.2°C by end of century.

Pathway to net zero emissions

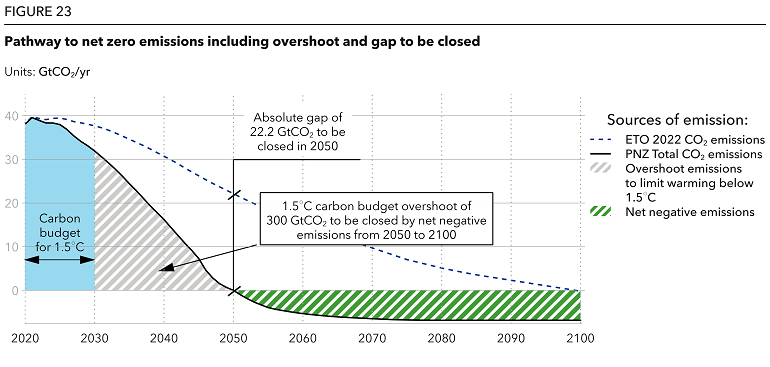

The ETO forecast has 22 GtCO2 of annual emissions in 2050. Taking those emission to zero is not enough. Even if the world managed to bend the emissions trend to intersect zero at 2050, the 1.5°C carbon budget would be exhausted by 2029.

That means to return to a 1.5°C trajectory by 2100, the cumulative emissions between 2030 and 2050 – an ‘overshoot’ of some 300 GtCO2 — need to be removed in the second half of this century. This involves a massive carbon capture and sequestration effort.

While the majority (65%) of global warming is associated with CO2, other greenhouse gases, including methane, also need to be controlled. This involves, for example, changes in agriculture or aerosol use.

We do not model this but have chosen instead to use the IPCC scenarios in line with ‘very low’ and ‘low’ non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions estimates in our Pathway. The focus of our Pathway is on CO2 emissions associated with energy use

DNV stated.

Reaching net zero requires both a deceleration of emitting sources (coal, oil and gas) and an acceleration of low- or zero-emission technologies far beyond the ETO forecast. In addition, a very large scaling up of both carbon capture and storage (CCS), direct air capture (DAC) and nature-based solutions will be needed to remove the overshoot of emissions accumulated before 2050. Up to 7 GtCO2 per year must be removed through to 2100.

The cost of transition

The roll-out of renewables and grid build-outs will require very large upfront investment. Some therefore consider the transition to be ‘unaffordable’. But the results of the report suggest the opposite.

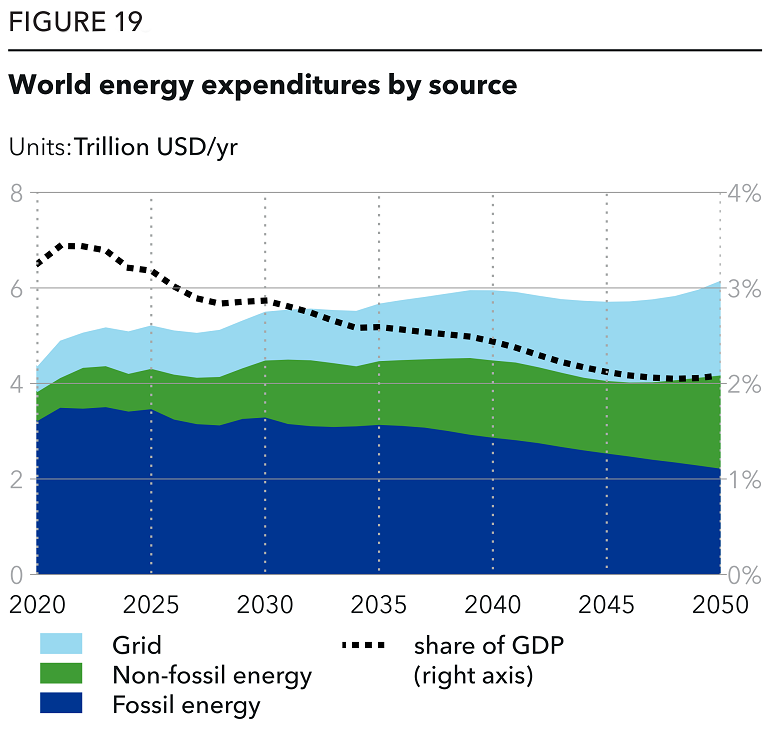

Namely, the forecast shows energy costs remaining stable and the share of energy expenditures in global GDP declining – from 3.4% in 2021 to 2.1% by mid-century.

The energy transition thus involves a substantial green prize, paying dividends to society for generations to come, even before factoring in the avoidance of incalculable costs associated with climate damage.

In fact, total world energy expenditure was USD 4.9trn in 2021. DNV further projects world energy expenditure to increase 26% to USD 6.2trn by 2050 – far below the 107% increase in global GDP over the same period.

The unit cost of energy will stay stable around 11-12 USD/GJ even with a fundamental reshuffling in energy expenditure by source. Between 2021 and 2050, fossil expenditure will reduce 40% in USD terms, non-fossil will triple, and grids will also almost triple.

However, while the transition is affordable globally, expenditures on the provision of energy are not market prices paid by the consumer, which include margins, taxes and/or subsidies – and upfront investments in end-use items like EVs and heat pumps.

Rise of renewables

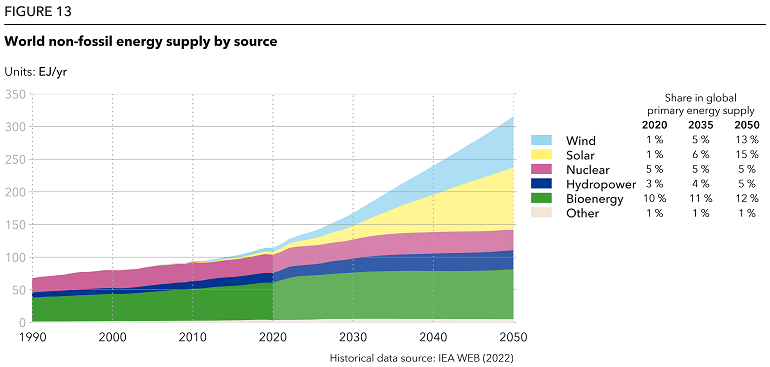

According to the report, by 2050, the global power system will be 70% reliant on variable renewable energy sources (VRES). Coal and gas decline to 4% and 8% respectively of the power mix by 2050, when they are largely confined to providing flexibility and backup in a power system.

Specifically, until 2050, solar capacity increases 22-fold, wind capacity 9-fold, onshore wind 7-fold, and offshore wind 56-fold. Driving this are both plunging costs and a growing realization that VRES offer the cheapest and quickest route to both decarbonization and energy security.

The global weighted average levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for solar PV is currently around USD 50/MWh for solar and USD 120/MWh for solar+storage. This reduces to around USD 30/MWh by mid-century for solar PV, with individual projects well below USD 20/MWh.

Solar+storage cost is currently more than double that of solar PV without storage. Falling battery prices will narrow this gap to around 50% by mid-century.

Within a decade, about one fifth of all PV will be installed with dedicated storage, and by mid-century this rises to half. Global annual solar installations will reach some 550 GW per year of net capacity additions by 2040

DNV predicts.

Rapid electrification

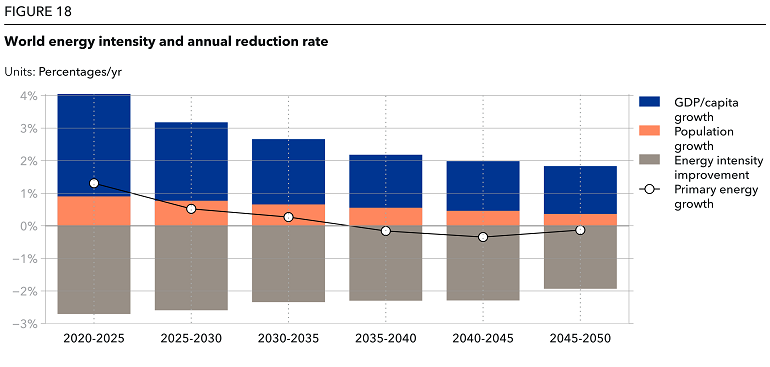

High energy prices in 2022 have highlighted speed with which energy efficiency initiatives can significantly, and often permanently, ratchet down energy use and costs.

Removing inefficient and expensive energy practices is a defining feature of the energy transition over the next three decades and should be the top priority for individuals, companies, and governments focused on transitioning faster and on achieving energy security, ETO notes.

The report also added that after 2035, the reduction in energy intensity is stronger than the combined growth of population and GDP per capita. As a result, growth in global primary energy supply turns negative and primary energy supply peaks in the mid-2030s.

In addition, dapid electrification powered by renewables is the core driver of accelerating energy efficiency in the next three decades. The typical thermal efficiency for utility-scale electrical generators is some 30 to 40% for coal and oil-fired plants, and up to 60% for combined-cycle gas-fired plants.

In comparison, solar PV and wind generation are 100% efficient, and conversion losses as a percentage of input energy in power generation reduce from 51% in 2019 to 19% in 2050.

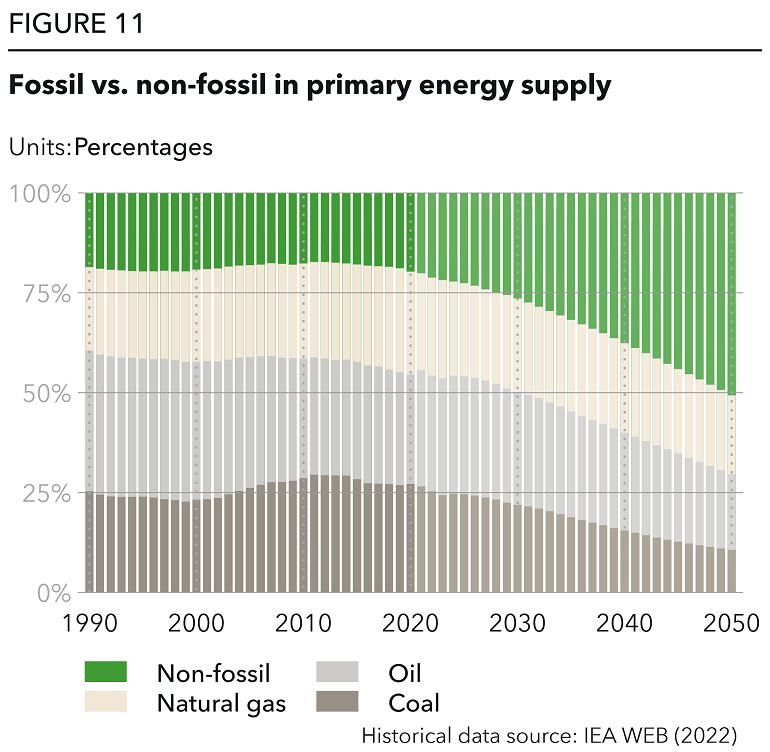

Fall of fossil fuels

- Coal: Peaked at 8 Gt per year in 2014. Since then, total demand for coal has and will decline. The pandemic reduced coal demand by 7% in 2020. The demand rebound will not reach its previous peak, instead coal use will fall almost two-thirds from current levels by 2050.

- Oil: In 2020, demand was 75 million barrels per day (Mb/d) excluding natural gas liquids and biofuels. We predict a peak in 2025, at 86 Mb/d, 15% above today’s level, before going into steady long-term decline. Demand will decrease slowly between 2025 and 2035, after which the decline becomes relatively steep, averag- ing -2.4% per year over the period 2035–2050. In 2050, expected global oil demand of 56 Mb/d (115 EJ) will be 45% lower than today.

- Natural gas: Peaks in 2036 and slowly tapers off to end some 10% below today’s levels. It surpasses oil as the largest source of primary energy in the late 2040s. Gas has staying power owing to its diversity of uses — half of the demand for gas is as final energy in manufacturing, transport and buildings, and the other half through transformation for other final uses like electricity, petrochemicals and hydrogen production. Demand will vary considerably across regions: declining in OECD countries, growing in Greater China, but peaking there in the early 2030s, and tripling in the Indian subcontinent by 2050.