The sinking of the container ship ‘El Faro’ in October 2015, claimed the title of one of the biggest marine tragedies in the recent US history. The ship had sailed directly into the path of Hurricane Joaquin, with NTSB and USCG noting that the key cause of the accident was the Captain’s failure to handle the ship against the storm and make appropriate use of weather data. As a result, all those on board perished in the sinking.

Accident details: At a glance

Type of accident: Sinking

Vessel(s) involved: ‘El Faro’ (container ship)

Date: 1 October 2015

Place: Acklins and Crooked Island, Bahamas

Fatalities: 33

The incident

At the time of the sinking, EL FARO was on a US domestic voyage with a full load of containers and roll-on roll-off cargo bound from Jacksonville, Florida to San Juan, Puerto Rico.

As EL FARO departed port on September 29, 2015, a tropical weather system that had formed east of the Bahamas Islands was rapidly intensifying in strength. The storm system evolved into Hurricane Joaquin and defied weather forecasts and standard Atlantic Basin hurricane tracking by traveling southwest. As various weather updates were received onboard EL FARO, the Master directed the ship southward of the direct course to San Juan, which was the normal route.

[smlsubform prepend=”GET THE SAFETY4SEA IN YOUR INBOX!” showname=false emailtxt=”” emailholder=”Enter your email address” showsubmit=true submittxt=”Submit” jsthanks=false thankyou=”Thank you for subscribing to our mailing list”]

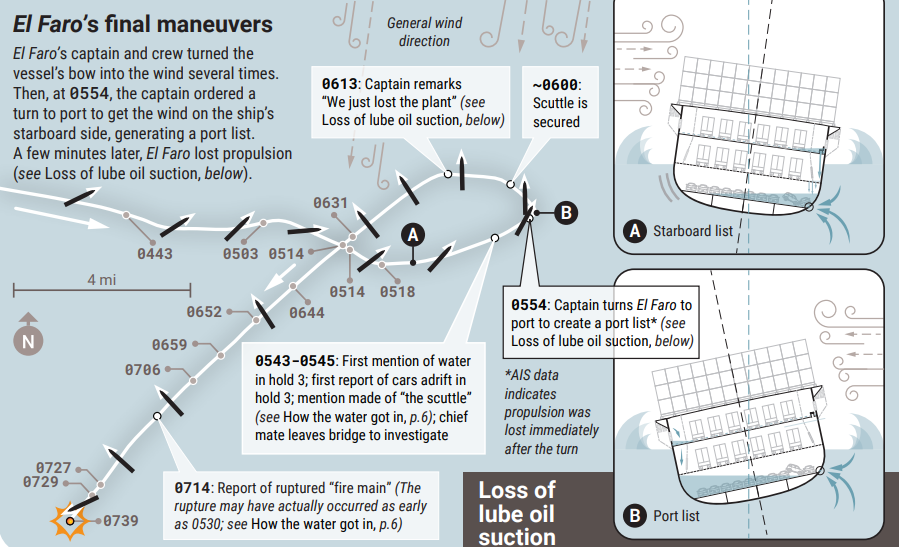

The Master’s southern deviation ultimately steered EL FARO almost directly towards the strengthening hurricane. As EL FARO began to encounter heavy seas and winds associated with the outer bands of Hurricane Joaquin, the vessel sustained a prolonged starboard list and began intermittently taking water into the interior of the ship. Shortly after 5:30 AM on the morning of October 1, 2015, flooding was identified in one of the vessel’s large cargo holds.

At the same time, EL FARO engineers were struggling to maintain propulsion as the list and motion of the vessel increased. After making a turn to shift the vessel’s list to port, in order to close an open scuttle, EL FARO lost propulsion and began drifting beam to the hurricane force winds and seas.

At approximately 7:00 AM, without propulsion and with uncontrolled flooding, the Master notified his company and signaled distress using EL FARO’s satellite distress communication system. Shortly after signaling distress, the Master ordered abandon ship. The vessel, at the time, was near the eye of Hurricane Joaquin, which had strengthened to a Category 3 storm. Rescue assets began search operations, and included a US Air National Guard hurricane tracking aircraft overflight of the vessel’s last known position. After hurricane conditions subsided, the US Coast Guard started additional search operations, with assistance from commercial assets contracted by the vessel’s owner. The search located EL FARO debris and one deceased crewmember. No survivors were located during these search and rescue operations.

Captain’s failures under the microscope

As NTSB explained in a digest report, from early in the voyage, the captain made decisions that put his vessel and crew at risk, including:

- Making only minor course corrections to avoid Joaquin;

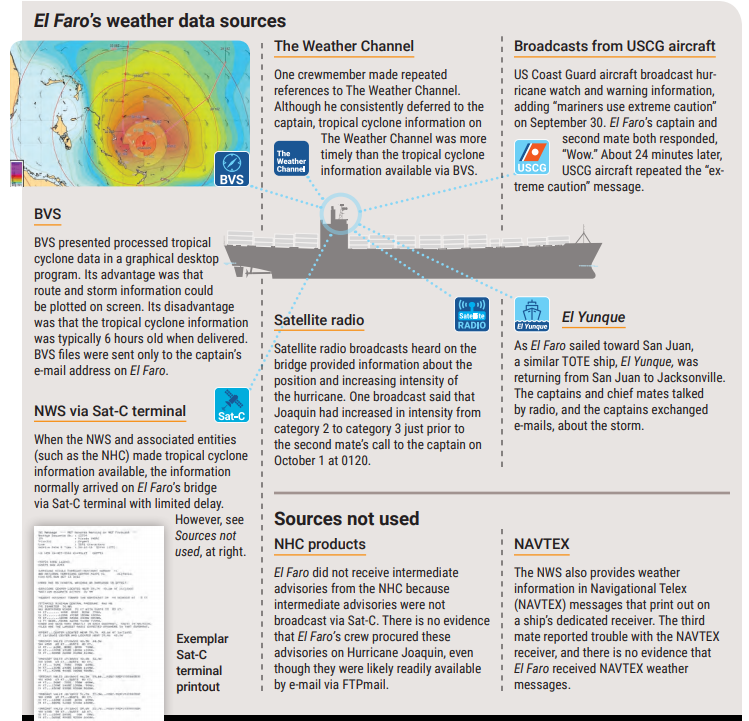

- Relying on outdated weather sources;

- Declining to change course or return to the bridge, even after receiving three calls from deck officers when he was not on the bridge;

- Introducing a port heel to shift water on the weather deck from starboard to port.

What is more, the captain continually referred to hours-old weather information from BVS. Watchstanders on the bridge were routinely getting more current information from the Sat-C terminal and from programs on satellite radio.

In addition, after the ship lost propulsion, the captain continued to voice his expectation that propulsion would be restored. The general alarm did not ring until 0727 and the captain did not muster the crew until 0728.

On top of that, two crew of the bridge suggested that they disagreed with the captain’s decisions, but the captain disregarded their concerns. Although bridge resource management stresses assertiveness, the traditional maritime culture emphasizes on the captain’s authority onboard. TOTE had not effectively implemented BRM which involves modernizing centuries-old roles.

READ THE INVESTIGATION REPORT HERE

Crew not fully familiar with ship’s systems

Despite the fact that the captain’s actions played a significant role in the accident, USCG’s report identified more factors that contributed as well. Specifically:

- TOTE did not provide the tools and protocols for accurate weather observations.

- The loss of propulsion resulted in the vessel drifting and aligning with the trough of the sea, exposing the beam of the vessel to the full force of the sea and wind.

- The EL FARO crew did not have adequate knowledge of the ship or ship’s systems to identify the sources of the flooding, nor did they have equipment or training to properly respond to the flooding.

- A lack of effective training and drills by crew members, and inadequate oversight by TOTE, Coast Guard and ABS, resulted in the crew and riding crew members being unprepared to undertake the proper actions required for surviving in an abandon ship scenario.

- When the Master made the decision to abandon ship, approximately 10 minutes before the vessel sank, he did not make a final distress notification to shore to update his earlier report to TOTE’s Designated Person Ashore that they were not abandoning ship. This delayed the Coast Guard’s awareness that EL FARO was sinking and the crew was abandoning ship, and impacted the Coast Guard’s search and rescue operation.

- The cumulative effects of anxiety, fatigue, and vessel motion from heavy weather degraded the crew’s decision making and physical performance of duties during the accident voyage.

- EL FARO’s conversion in 2005-2006, which converted outboard ballast tanks to fixed ballast, also severely limited the vessel’s ability to improve stability at sea in the event of heavy weather or flooding.

- Although EL FARO’s open lifeboats met applicable standards (SOLAS 60), they were completely inadequate to be considered as an option for the crew to abandon ship in the prevailing conditions.

LEARN FROM THE PAST: Read in this series

Lessons learned and recommendations

When the US Coast Guard published its final report on the accident, it also proceeded to certain recommendations. Among others, USCG recommended that Commandant direct a regulatory initiative:

- To review U.S. regulations, international conventions, and technical policy to initiate revisions to ensure that all ventilators or other hull openings, which cannot be closed watertight or are required to remain normally open due to operational reasons such as continuous positive pressure ventilation, should be considered as down-flooding points for intact and damage stability.

- To eliminate open top gravity launched lifeboats for all oceangoing ships in the U.S.commercial fleet.

- To require that a company maintain an onboard and shore side record of all incremental vessel weight changes, to track weight changes over time so that the aggregate total may be readily determined.

- To require review and approval of software that is used to perform cargo loading and securing calculations.

- To require that all Personal Flotation Devices on oceangoing commercial vessels be outfitted with a Personal Locator Beacon.

- To develop a shipboard emergency alert system that would provide an anonymous reporting mechanism for crew members to communicate directly with the Designated Person Ashore or the Coast Guard while the ship is at sea.

- To request that NOAA evaluate the effectiveness and responsiveness of current National Weather Service (NWS) tropical cyclone forecast products, specifically in relation to storms that may not make landfall but that may impact maritime interests.

- To require that all cargo ships have a plan and booklets outlining damage control information. • To update 46 CFR to establish damage control training and drill requirements for commercial, inspected vessels.

- To require electronic records and periodic electronic transmission of records and data to shore from oceangoing commercial ships.

- To explore adding an OCMI segment to Training Center Yorktown’s Sector Commander Indoctrination Course for prospective officers who do not have the Prevention Ashore Officer Specialty Code, OAP-10.

- To update NVIC 2-95 and Marine Safety Manual Volume II to require increased frequency of ACS and Third Party Organizations (TPOs) direct oversight by attendance of Coast Guard during Safety Management Certificate and Document of Compliance audits.

- To establish and publish an annual report of domestic vessel compliance.

- To implement a policy requiring that individual ACS surveyors complete an assessment process, approved by the cognizant OCMI, for each type of delegated activity being conducted on behalf of the Coast Guard.

- To explore adding a Steam Plant Inspection course to the Training Center Yorktown curriculum.

- To require that all existing cargo vessels meet the most current intact and damage stability standards.

READ THE INVESTIGATION REPORT HERE

Speaking about what the industry has learned after the EL Faro sinking, Anastasios Chrysikopoulos, Chief Officer at Maran Dry Management Inc., said that the study of human factors is of much importance to understand how to facilitate the people working on board.

Some of the human attributes like professionalism are hard to train, but such attributes can be guided by company procedures and regulations

He added that well defined and structured company policies and regulations can also assist the crew in vital decision-making situations to choose between efficiency and thoroughness.

In the El Faro case the crew and particularly the captain’s decisions were influenced by the human element, but if the company had established an appropriate safety culture within the company, some negative influences could have been avoided

In addition, in an exclusive interview with SAFETY4SEA, Rear Admiral John P. Nadeau, Assistant Commandant for Prevention Policy, US Coast Guard, highlighted that the adoption of a proactive safety culture, remains the number one priority.

As he explained, this incident is a call to action for the entire maritime community, as it was caused by poor seamanship, as well as a failure of the safety framework that should have triggered a series of corrective actions, which could have prevented it.

As he explained, this incident is a call to action for the entire maritime community, as it was caused by poor seamanship, as well as a failure of the safety framework that should have triggered a series of corrective actions, which could have prevented it.

We should all honestly assess our own safety management and oversight responsibilities and ask ourselves if we’ve truly adopted a safety mindset and seek continuous improvement, or if we’re simply doing the minimum necessary to maintain compliance

El Faro the stepping stone to better maritime safety

Last year, the US House of Representatives approved a legislation to address maritime transportation safety issues raised by the El Faro sinking.

The Save Our Seas Act combines several pieces of bipartisan legislation recently approved by the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee, including:

- The Save Our Seas Act promotes national and international efforts to address the increasing amount of marine debris into the oceans. This provision urges the administration to support research and development on systems and materials that would reduce the amount of waste that enters the ocean and work with nations that discharge large amounts of waste into the ocean by sharing technologies and infrastructure to prevent, reduce, or mitigate those land-based sources from entering the marine environment.

- The Maritime Safety Act of 2018 addresses maritime safety issues that were raised in the Commandant of the Coast Guard’s final action memo in response to the sinking of the El Faro. This provision of the bill will ensure timely weather forecasts, emergency safety gear with locator beacons, float-free voyage data recorders with integrated emergency position indicating beacons, and other safety improvements.

- The US Coast Guard Blue Technology Center of Expertise Act (H.R. 6206) establishes a Blue Technology Center of Expertise to help promote awareness within the US Coast Guard of the range and diversity of so-called Blue Technologies – new and emerging maritime domain awareness technologies, especially more cost effective unmanned technologies – and how the use of such technologies could enhance u Coast Guard mission readiness and performance. The bill also enables the sharing and dissemination of Blue Technology information between the private sector, academia, nonprofits and the Coast Guard.

The El Faro sinking is now considered one of the biggest marine tragedies in the recent US history. Poor seamanship, inadequate training, and wrong decisions played a key part. However, the industry must learn from this tragic accident, in order to prevent similar ones in the future, and protect seafarers.

The Tote Shipping Company had to have put pressure upon the captain to sail with a hurricane somewhere along the route, to cause the captain to take such a risk. The ship should have traveled behind the Bahama Islands, West of them, so the ship had the ability to duck behind one of them. This was a much longer, more expensive route, which the Tote Company must have put pressure to not do. Once the captain realized, by the high seas, he was in the eye of the hurricane; it was too late. The crew officers, who had not spoken with; had been pressured by the company, wanted to veer far West behind the Bahama Islands and stop behind one of them, or to turn around. ‘Pressure’ can be indirect: “You cost the company a lot of wasted money when you chartered the two tug-boats to steer the ship to port last time when the ship’s steering was hit & miss due to a malfunction.”